4.3 The psychological contract

The psychological contract is a theory that relates to the expectations that exist between an organisation and its staff (and/or volunteers). It was originally based on paid work, but it has also been found to be useful in understanding volunteers’ motivations and why they might stay or leave their volunteering positions.

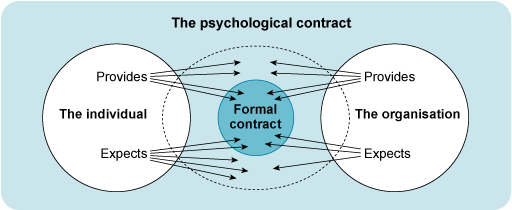

The theory suggests that people’s motivations come from the relationship between the individual and the organisation (or other group) they work for (see Figure 5).

The psychological contract is essentially a set of expectations. The individual has a set of outcomes or rewards that he or she expects in return for doing the work of the organisation. In paid work, part of this would be the person’s wages, promotion, feedback, staff development, and so on. Similarly, the organisation has certain expectations of what it wants the individual to contribute to the work of the organisation, and certain rewards and outcomes that it will give the individual in return.

Unlike employment contracts or other formal agreements, the terms of the psychological contract are not usually written down or even mentioned. This means that in practice some people are unaware of their organisation’s expectations of them.

Mismatch in expectations

The examples in Box 4 illustrate the psychological contract and the conflict caused by a mismatch in expectations.

Box 4 Mismatching expectations

Example 1

An occasional volunteer with an environmental organisation agrees to attend meetings of the management committee and be the Honorary Secretary, taking the minutes. Her psychological contract includes – in the limited time I have, this is the most useful way I can make a contribution, and I’ll be appreciated for this.

The staff see her interest in the meetings as a basic commitment to the work of the organisation and seek to draw her in further. They invite her to help out at a volunteer recruitment open day. This will involve interviewing potential volunteers. They also ask her to join a sub-group looking at future plans for the organisation.

The result is that the volunteer feels put upon and mistreated and the staff start to feel she is not really committed and involved. Before the next AGM the volunteer announces that she will have to resign the post.

Example 2

Mo has been volunteering in a charity shop every other Tuesday for five years. He started volunteering in order to meet people, as he was feeling lonely after his wife passed away. He likes the other volunteers in the Tuesday team and has got to know regular customers.

A new manager decides she does not need so many volunteers on Tuesdays. She asks Mo and two other volunteers to change their day to a Thursday.

The volunteers don’t mind this in principle, but Mo tries it for one week and finds that he has nothing in common with the new team, who work in a different way and are less sociable. He gives up his volunteering role.

Activity 9 Thinking about the psychological contract

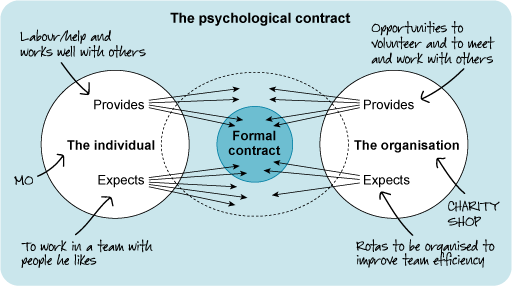

Look back to Example 2 in Box 4. What do you think are the terms of Mo’s psychological contract with the charity shop?

Try to express this visually by drawing and annotating your own version of Figure 5.

Comment

This is one way to draw the example – you may have expressed it differently.

The key thing to think about here is expectations. People are often not fully aware of their expectations or they may find it difficult to express them. They may lack confidence or feel it is somehow not legitimate to talk about their expectations. People’s and organisations’ expectations change over time and a psychological contract that was balanced at one point may become unbalanced.

A point to emphasise here is that volunteers do not have a formal contract in the same way that paid employees do. The psychological contract is a way of thinking about your own volunteering and how organisations seek to improve the experience of volunteering, which will then also provide positive benefits for the organisation and service users.