4.1 Inspiring the Victorians

There was more to Orientalism than that of course, including a pervasive interest in the lands of the Bible. In England, using the invaluable resource of the British Museum, certain later Victorian artists were able to study Egyptian painting first-hand, and in some cases to incorporate it into their own work to enhance the effects they sought, ranging from a form of historical truthfulness to a sense of the exotic.

Activity 5 Drawing inspiration from the past

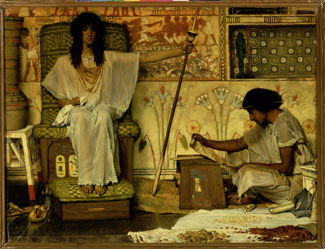

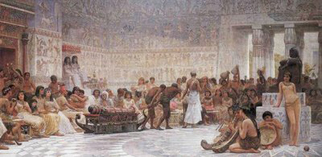

Look at these three paintings which drew inspiration from the Nebamun tomb wall paintings that were displayed in the British Museum (Figures 6, 7 and 8). Generally speaking, how do you think these artists have used the ancient paintings?

Discussion

The artists have included elements of the tomb paintings to give a kind of ‘authentic’ flavour to their own artworks, which are an eclectic reconstruction of Egyptian life, combining an interest in the Bible with a fascination with the exotic (even, in Victorian terms, the somewhat risqué). Yet the way the ancient paintings have been shown is itself anything but authentic. You will become more familiar with the Nebamun paintings later, but if you look closely you will be able to see how the nineteenth-century artists have adapted the ancient works to their own compositions.

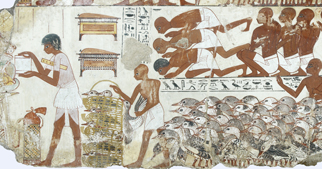

In the Alma-Tadema, the scene behind Joseph has been ‘stretched out’ to accommodate his chair back. In the original painting (see the close up in Figure 9), the standing scribe at the far left is much closer to the kneeling farmers and the geese to the right. To fill the space created in the upper row of figures above Joseph’s head, an extra group of feet has been added. And of course, perhaps most telling of all, is the fact that paintings from a tomb have been transformed into decorations for a living-room.

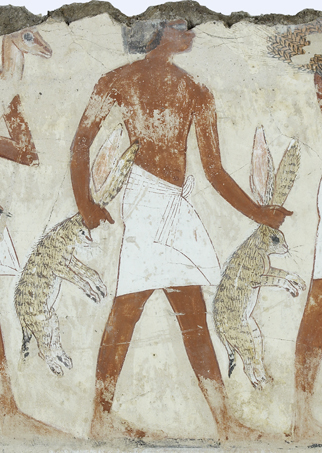

In the Weguelin, the artist has ‘synthesised’ two separate ancient fragments. As you can see, the scene showing the kneeling farmers, the geese, and the standing scribe (the same fragment used in the Alma-Tadema) ends with the table of offerings just upward and to the left of the foreground figure’s head. The space further to the left of that is filled by an image taken from an entirely different scene, showing offering-bringers carrying wild desert hares (Figure 10). You will study these paintings in detail in Week 3.

As you will see later, Egyptian art involved a completely different set of representational conventions from the post-Renaissance European Academic tradition. Yet here these academic painters simply assimilate the Egyptian pictures into their own brand of ‘realism’, employing the flat paintings from ancient tombs as a decorative feature of their own artfully constructed spatial illusion.