1 Exploring the evidence

One of the principal motors of modernism was the drive to separate image from narrative; indeed abstract art can be seen as the culmination of a tendency to particularise the visual begun by Lessing in 1766. In ancient Egyptian art, the opposite is the case. The linguistic aspect is up there on the wall with the pictures, reinforcing them, interpreting them, even exhorting the spectator to respond.

Key point

The complementary relation of word and image in the ancient Egyptian tomb-chapel is a point worth emphasising. Recent postmodernist theory has frequently used the language of language to talk about images: treating the picture as a 'text' to be read. But for much of the modern period, beginning in the eighteenth century and with redoubled emphasis in the twentieth, the theory of art sought to distinguish pictures from words.

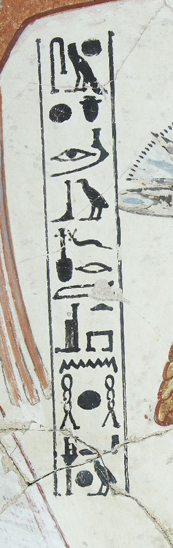

To the modern, non-specialist viewer, however, the picture is the thing: the wonderfully vivid cattle and geese, the dancing girls, the handsome couples. To all but a few highly-trained Egyptologists the hieroglyphs are no more than a general signifier of 'Egyptianness', along with the sideways feet and the wigs. Their specific message is lost on us (Figure 2).

Yet to the literate ancient Egyptian viewer – a very small percentage of the society as a whole – the hieroglyphs would have been at least as important as the pictures, conferring the picture’s particular meaning in its given context. The life stories of tomb-owners were usually given by the narrative texts. In fact the paintings tell us nothing particular about Nebamun, apart from the fact that he aspired to a conventional elite lifestyle. Even when he personally features in the paintings, the images are not likenesses. The agricultural scenes may have been chosen to link with his work, but agricultural scenes also occur in the tombs of people who were not grain-accountants. The only specific thing we know comes from the texts: his name and title.

If the tomb had remained intact, other texts would have told us the names of his parents and perhaps even a version of his life-story in the form of a ‘tomb autobiography’, as if narrated by Nebamun himself from beyond the grave. But as it is, the damaged hieroglyphic captions tell us only that Nebamun was the Scribe and Grain-accountant in the Granary of Divine Offerings in the Temple of Amun at Thebes (Figure 3). This means he was an official in a very important institution. Not a ‘minister’ or ‘secretary of state’, in modern political terms, but something like a middle manager or a civil servant in an important ministry.

Before and during the Eighteenth Dynasty Amun was the most important of the gods worshipped in the temple complex at Thebes. Some ancient Egyptian names are very common, as in any culture, and many ‘Nebamuns’ have been identified by Egyptologists working on objects from the Theban necropolis (Figure 4), as well as in the necropolis itself. This is unsurprising, since the name translates as ‘My Lord is Amun’.