5 Tomb layout

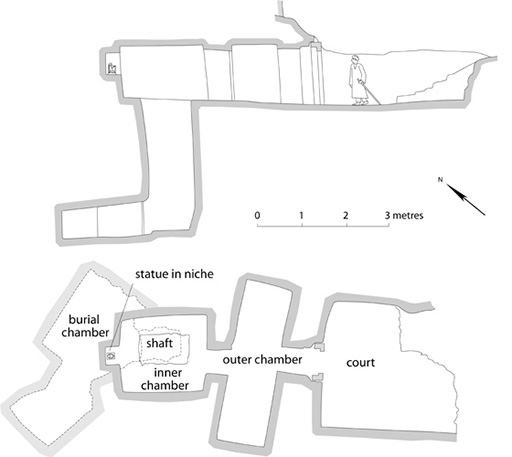

Typically one of these tombs would consist of three parts. First, as one approached, one would walk through a whole village of tombs before arriving at an entrance area cut into the hillside. This consisted of a high wall surrounding a doorway, with a sheltered courtyard in front of it. Tombs were ideally built on an east–west axis, the directions of the rising and setting sun respectively. The east represented the land of the living, the west the land of the dead. The entrance into the courtyard would be from the east (Figure 17). The door into the tomb-chapel itself would be wooden, with a decorated stone surround and above it was often a niche for a statue, facing the east. Usually a frieze of so-called funerary cones, set in the wall with the round end visible, ran around the top of the wall just below the cornice. The importance of these is that they were stamped with the name and titles of the tomb-owner and family members.

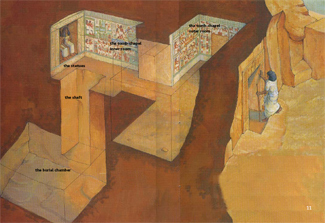

Inside the door was a passage, rectangular in section, and either more or less steep depending on the terrain, but basically leading either into the hill or below the ground (Figure 18). This passage led to what was usually the first of two rooms. This first room was normally transverse to the entrance passageway and was decorated with paintings on all its walls. The ceiling was painted too, often in a pattern imitating decorative textiles. Beyond this room would be another passageway leading from the middle of the opposite wall into the second room. This led away longitudinally, giving an overall T-shape to the tomb-chapel. This design is the commonest, though there are variations – sometimes a single room, and sometimes even a larger room with columns holding up the roof. But the T-shape is the norm (Figure 19). At the far end of the second room, that is to say at the westernmost end of the chapel, there would be a niche containing a statue of the tomb-owner and his wife.

Somewhere below the floor of one of the rooms of the chapel, or even the courtyard, there would be a vertical shaft leading down to the actual burial chamber. This contained the coffin and the burial goods, but most often remained undecorated. The chamber was sealed with either a wooden door or stones, and the passage was backfilled after the burial to prevent access. Because the tombs were an important family site, however, they could be re-opened for the addition of further burials in subsequent years.

The tomb-complex, then, was on three levels: the upper level, the courtyard, with its entrance leading from the outside world into the interior. The next level slightly below ground containing the two decorated rooms of the chapel, and the third level, deeper underground containing the coffin and mummy itself. It is important to grasp that this layout is not merely physical, not merely contingent. The layout of the tomb-chapel, and the tomb overall, in effect figures the journey of the deceased towards the afterlife. Each level had a different spiritual focus: the first, the courtyard, on life and the worship of the sun god; the second, the tomb-chapel, on the deceased tomb-owner his status and achievements; the third, the burial chamber itself, on Osiris and the underworld.

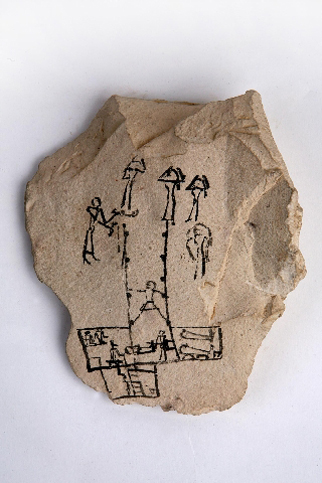

In one remarkable drawing, depicting a tomb during a funeral, the layout of such a tomb is preserved on an ostracon (Figure 20). The depicted scene shows, at the top, a priest and a group of weeping women. In the centre a figure is descending the shaft. At the bottom can be seen another figure with the coffin, as well as (to the left) a jackal-headed priest and (to the right) a chamber already containing two coffins.