9.5 Hunting in the marshes

To return then to the first of the two questions above: what are the consequences of this for the way an Egyptian picture is organised?

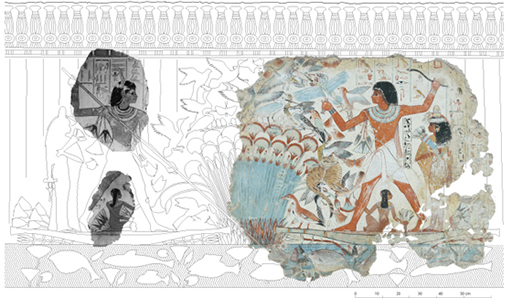

In the tomb-chapel of Nebamun we can see many of these conventions at work, even though the pictures are considerably loosened in other ways. Take ‘Hunting in the Marshes’ (Figure 32). You will already be familiar with this image, but look again bearing in mind Schäfer’s analysis.

What do you notice about Nebamun’s body?

We have already noted how idealised it is, in general: well proportioned, muscular, and with glowing skin. We have also seen how the various ‘components’, despite a relatively lifelike initial impression, are actually not. His legs are represented from the side.

Watch this video in which Richard Parkinson and Paul Wood talk about conventions in painting feet

Feet are a surprisingly complicated matter. In this image the toenails contradict the initial sense of which feet we are looking at (Figure 33). My initial thought was that his left foot was forward, his right foot back. But whereas, if that were the case, the toenail on his back foot would be correct, the forward foot also has a visible toenail, which it would not have ‘perspectivally’. Male feet are always represented in Egyptian art as if seen from the inside. Another peculiarity is that the arch of the foot, which would indeed be seen if regarded from the inside, is represented as going all the way through; which in fact it does not. The outside of a human foot closes the arch. But in Egyptian art there is always a transparent space – even to the extent of other things being able to be seen through it, in certain paintings. Women, who are less important than men in the Egyptian hierarchy are represented with relatively naturalistic pairs of feet.

Nebamun’s lower torso around the navel and buttocks is seen from the side. At first glance his upper chest seems to be represented as if from the front, but it isn’t: the rearward line describes the outline of the back while the forward line is also a profile complete with nipple (Figure 34). The shoulders seem to be viewed from the front, but actually the arms would only make realistic sense if his upper torso were being viewed from the rear. If his chest is seen from the front, his left arm is where his right arm would be, and his right arm is the opposite. Lastly, his head is in profile, but the eye is depicted as if seen front-on.

What other ‘grammatical’ features of the composition strike you? Did you notice that his wife and daughter are ‘sized’ not according to where they are in space, but according to their relative importance.

Finally, look at the reconstruction drawing in Figure 35. You can see that the whole surviving image is then duplicated in some of its most important features in the now lost left hand side, in order to produce not a truthful image in terms of the spectator’s viewpoint, but a symmetrical, well-ordered image of Nebamun performing two activities (fowling and fishing) in the marshes.

Of course, not all the images in the tomb-chapel are symmetrical. But this does not mean that they are ordered according to the sense of a visual climax such as the kind of triangular composition often found in Renaissance and Academic painting. Figures are not shown in spatial depth; instead they tend to have a one-after-another repetitive sequencing, dispersed laterally across the image.