9.6 Produce of the Estates

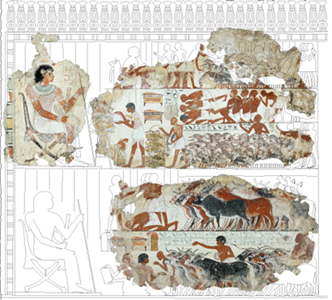

Look now Figure 36 showing Inspection of the Produce of the Estates.

What feature strikes you about this wall that is not so evident in the previous scene?

We are presented here with another crucial Egyptian convention: the register line.

It is not easy to say what register lines ‘are’ – though Schäfer says they ‘one of the strongest signs’ that we are in the presence of object- or image-centred rather than spectator-centred representation (p. 163). They are not ‘ground’ as such, in the way that figures stand on representations of a horizontal ground plane in a perspective representation.

They are certainly devices for ordering the ‘lateral’ space of the wall – that is the height and the width, the two-dimensional space, and for organising the figures across that space. But they do not organise three-dimensional space. In fact it is probably true to say there is no three-dimensional space in Egyptian paintings outside of the lines enclosing figures (Figure 37).

Certain devices can be used to indicate spatial depth, such as the overlapping of the bodies of the cattle in the bottom register and the three human figures in the top half of that bottom register. But there is nothing to say where the ‘top’ cluster of cattle is relative to the bottom cluster.

There is no consistent convention saying that something shown above is further away, as it conventionally is in perspectival representation.

The thing which is difficult for ‘modern Western’ (or ‘post-Greek’) eyes to work out is the combination of naturalistically detailed parts of figures with no correspondingly naturalistic space for those figures to inhabit.

Schäfer is, however, absolutely clear on one point here: the pictures are not like this because the Egyptian draughtsmen found foreshortening or three-dimensional illusionism ‘too difficult’ or because they ‘could not’ reproduce those effects (p. 84). Rather, they were rejected – for the reasons we have rehearsed already.