10.1 Egyptian ‘genres’

We have already noted how, in the Western classical–academic tradition, a system of ‘genres’ was evolved to rank types of subject matter.

In Egyptian art, the various representational conventions we have been observing here were evolved very early in Egyptian history. These devices were not present, or only partially or hesitantly so, in pre-Dynastic times. But by about the Third or Fourth Dynasties, that is, before the middle of the third millennium BC, they were present in fully-fledged form. And with remarkably little variation they remained in place until the end of Ancient Egypt in the Roman period, almost two and a half thousand years later.

However, as well as the various ‘grammatical’ devices for the making of representations, the subjects to be represented were also formulated at the same time. They likewise persisted throughout Egyptian history.

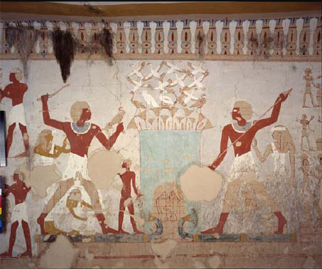

We have become familiar with an image of Nebamun hunting in the marshes in 1350 BC, but despite its naturalistic particulars, this image is far from specific to his tomb. Similar images can be seen in other Theban tomb-chapels of the New Kingdom (Figures 39 and 40).

But we can also see images of fishing and fowling in the marshes, with their protagonists doing exactly the same things – catching birds, hurling a throw-stick, spearing a fish – in the Old and Middle Kingdoms. The image of Sabni, Governor of Elephantine in Upper Egypt, shows him hunting in the marshes (Figure 41). It dates from c. 2175 BC in the late Sixth Dynasty, that is, eight hundred years before Nebamun.

The subject matter of the scenes – hunting in the marshes, inspecting the produce, the offering table, the banquet – is no less canonical than the visual grammar in terms of which the representations are organised.