4.1 From plan to wall

Once the scheme for a particular wall was agreed it then had to be sketched out on the wall surface itself.

The first stage was to lay down the registers. These were the horizontal baselines on which figures in Egyptian art were placed (see Figure 12), and that had been a convention from the beginning of the Dynastic period when the canon of Egyptian representation was being formulated in the early third millennium BC. This would be done with a string dipped in paint and ‘twanged’ down on the surface. One such length of string, wrapped round some artist’s brushes has actually survived from the tomb of Mentuhirkhopsef at Thebes

Once the registers were in place, the main figures were then sketched out in red. The draughtsmen who would do this would have been apprentices in the craft hierarchy, and their work would be checked by the master in overall charge of the work. He would make corrections or sometimes redraw the figure.

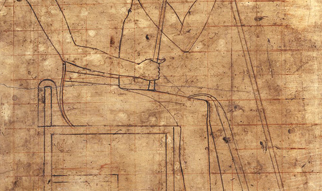

This figure-drawing process was complex and subject to considerable variation. Throughout Egyptian history, a template was followed, though despite the apparently Procrustean nature of the description, this was not as rigidly applied as it sounds. During the Old Kingdom there was a system of proportional guides that by the time of the late Eleventh to early Twelfth Dynasties of the Middle Kingdom had evolved into a grid (Figure 13).

This consisted of 18 squares, stretching from the soles of the feet up to the hairline of a standing figure. (For seated figures it was 14 squares.)

Despite the daunting description, however, the proportional grid is not responsible for the famous ‘stasis’ of Egyptian art. Its application varied not only over time but even within a single tomb. It was in essence a guide for the production of human figures with ‘correct’ proportions, rather than an absolute template.

In the Nebamun tomb-chapel, only the offering scene employed a grid, although overall, according to Robins, they had been very common in earlier Eighteenth Dynasty painted tomb-chapels. It was variable as to whether one grid would cover a whole wall or whether variably sized grids were used for different sized figures, and both methods could be employed in one tomb-chapel. By the later Eighteenth Dynasty, only large, formal figures were usually designed according to the grid, with smaller figures either being drawn in with just a few guidelines or even completely freehand.

Although this process would have prompted a certain rigidity in the figures, it does seem to have been used as an aid, rather than an absolutely inflexible requirement. It was scarcely more constraining than the ideal proportions associated with the European academic system many centuries later, or, come to that, the practice of ‘squaring up’ from a drawing to a larger design that is a commonplace of Western art. Indeed, the evidence from ostraca and papyri is that ancient Egyptian artists were perfectly capable of improvised freehand drawing, even a form of witty caricature exaggeration (Figure 14).

As Robins has established, tomb-painting was not a form of painting-by-numbers; the use of the grid was far from slavish and there was considerable scope for judgement and the exercise of choice on the part of the ancient artist-draughtsmen. And the tomb-chapel, we must remember, was a considerably formalised environment, as indeed is any religious space in any culture.