7 Selecting the fragments

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that in 1820 there was little comprehension of the original meaning of the scenes. This is not to say that there was none. In the wake of the Napoleonic expedition and the subsequent publication of the massive series of volumes De l’Egypte, Europeans, scholars and treasure-hunters alike would have had some knowledge of Egyptian painting, sculpture and architecture. But in the absence of an understanding of the language this would have been limited to a broad grasp of visual conventions rather than an ability to ‘read’ particular images. What it probably would have led to, in the case of figures such as d’Athanasi, Drovetti, Belzoni and others, was a sense of what was normal in Egyptian art, what was relatively run-of-the-mill, and what stood out in some way.

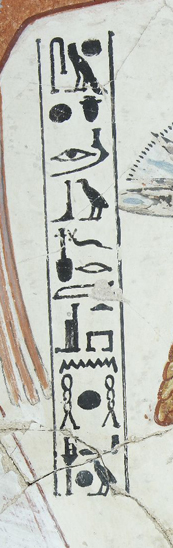

Hieroglyphs gave significant meaning to the scenes for their original viewers, but in the early nineteenth century they were meaningless (Figure 26).

How did d’Athanasi make his ‘selections’?

The readiest answer is that d’Athanasi picked the most vivid scenes, details almost; and at one level that is probably enough.

If we go a little further, however, and ask what it was that made one scene rather than another appear vivid, the selection becomes more noteworthy. There is nothing natural or universal about what appears interesting in a picture. The concept of a ‘period eye’ has been used by art historians to recover the sense that different people at different times have made of visual representations. This concept was originally developed by the twentieth-century historian Michael Baxandall (1933–2008) to shed light on the Italian Renaissance, but it applies equally to other cultures, and is a useful tool with which to avoid universalising our own local cultural preferences. Thus, to the ancient Egyptians themselves, relationships that were ignored by or even invisible to d’Athanasi, would have been crucial to the paintings’ significance. The meanings the paintings originally circulated, over 1300 years BC, would not have been the meanings d’Athanasi, and later Henry Salt or viewers at the British Museum saw in them. That is to say, the act of selection itself may be regarded as an act of production of a kind.

A lesson from the avant-garde

We have mentioned nineteenth-century art more than once in our approach to these paintings of 1350 BC, but here, unlikely as it may seem, there is a lesson to be learned from the twentieth century avant-garde. In the second decade of the century, Marcel Duchamp broke with a conventional practice of art making and developed the concept of the ‘ready-made’, which was of incalculable significance to the art of the later twentieth century.

The relevance of this to our present case is that Duchamp chose an existing object and nominated it as a work of art (thereby raising, almost at a stroke, various far-reaching questions about the nature of the work of art, the identity of the artist and the nature of the transaction involved when a spectator encounters a work of art that continue to resonate to this day) (Figure 27).

Duchamp’s gesture had the effect of broadening the parameters of what could be regarded as constituting a cultural intervention. In effect, it demonstrates that to make a selection is to produce a new meaning. Duchamp was the first to recognise this, and grasp some of its implications for art. But similar kinds of selections, interpretations, misinterpretations, translations and so on have been the stuff of cultural encounters from time immemorial.

Key point

The act of making a selection also makes a new meaning.

When, in 1820, d’Athanasi and others like him took the decision to keep some parts of a painting and reject or destroy others, they were making decisions that involved a complex mixture of aesthetic and cultural criteria. Such an act is manifestly culturally relative, the work of a different ‘period eye’ from that which originally saw the pictures and derived meaning from them in the tomb-chapel in 1350 BC (Figure 28). (And by the same token, of course, different from our own, post-Duchampian, not to say post-Hollywood, ‘period eyes’.)

What has been kept, and what has been lost?

For the most part it is the large ‘out of scale’ figures that have gone, as well as other elements such as the decorative borders or compositional features such as symmetry (e.g. the left-hand figure in Hunting in the Marshes).