8.1 The Bible

It is well-known that, at least up until the Napoleonic expedition, with its Enlightenment programme of scientific knowledge, the main driving force behind any European interest in Egypt was Biblical studies. In fact, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the two were not really to be separated. Science was regarded as shedding light on, even providing historical confirmation for, the Biblical story of the children of Israel: exiled in and ultimately escaping from the land of Pharaoh before arriving in their own Promised Land. In 1850, on his visit to Egypt, the French novelist Gustave Flaubert wrote of: ‘the old Orient, which is always young because nothing changes. Here the Bible is a picture of life today’.

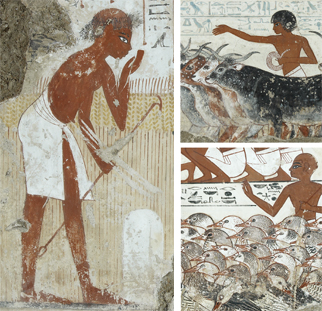

As we have seen, the Victorian painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema implicitly recognised that the Biblical Joseph was a kind of super ‘Grain accountant’, and some of the scenes from Nebamun’s tomb could potentially be used to illustrate Joseph’s story. (This is a considerable tradition: in twelfth-century mosaics in St. Mark’s basilica in Venice, the pyramids are represented as Joseph’s granaries: the stores he built to keep the surplus of the seven years of plenty before the onset of the seven lean years of famine.) It may be assumed that all sorts of scenes of ancient Egyptian daily life would have been grist to the mill for an audience willing to be enchanted by ‘authentic’ scenes of life as it was experienced by the actors in the Old Testament narrative.

Part of the appeal of genre-type scenes was the historical information they were assumed to offer about daily life in Biblical times (Figure 31). The pioneering Egyptologist Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) wrote a much-reprinted account of The Manners and Customs of the ancient Egyptians (1836) as well as A Popular Account of the Ancient Egyptians (1854) which he based on his familiarity with Luxor and the remains of ancient Thebes. His work drew on the influential fifth-century BC Greek account given in the Histories of Herodotus, but his main source was the paintings of daily life found in the Theban tomb-chapels. In particular, he illustrated the Nebamun paintings, which by then were in the British Museum.

In his accompanying text, Wilkinson underlined the importance of the pictures for the purchase they could give modern people on the lived experience of Classical and Biblical times:

Though the literature of the Egyptians is unknown, their monuments, especially the paintings in their tombs, have afforded us an insight into their mode of life scarcely to be obtained from those of any other people. The influence that Egypt had in early times on Greece gives to every inquiry respecting it an additional interest; and the frequent mention of the Egyptians in the Bible connects them with the Hebrew records, of which many satisfactory illustrations occur in the sculptures of Pharaonic times. Their great antiquity also enables us to understand the condition of the world long before the era of written history; all existing monuments left by other people are comparatively modern; and the paintings in Egypt are the earliest descriptive illustrations of the manners and customs of any nation.