8.3 Orientalism

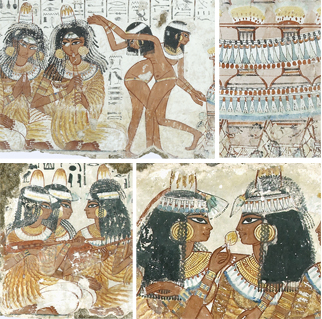

A third powerful strand that we can unravel from the constellation of factors that would have made some scenes stand out, is the early stages of the discourse of Orientalism. In the eighteenth century, British and French involvement in India had begun to launch a sense of different ways of life that was markedly different from medieval and Renaissance conceptions of the heathen and godless. In the early Renaissance, particularly in maritime cultures such as Venice, there was an openness to, indeed an embrace of, Eastern forms in art and architecture that subsequently froze over in the stand-off with Islam. But by the eighteenth century the balance of forces had changed, and Europeans were now encountering exotic cultures from a position of much increased power. These forms of life may have been non-Christian, decadent even, in the eyes of the church and its missionaries; but that did not mean they lacked allure. At this period the myth of the East was being consolidated, a heady mix of luxury, indolence and depravity that Europe constructed to set against, and to some extent to justify, its own perceived virtues of rationality and empiricism. The banquet scenes in Nebamun’s tomb-chapel must have struck a chord as resonantly as the animals and the Old Testament. All those figures, the slender beautiful women in their rich flowing robes, the men with their idealised physiques, the gold, the wine, the lotus flowers, and of course the almost-naked dancing girls, would have set bells ringing in any viewer with a flicker of interest in the risky territory of Otherness (Figure 33).