3.2.2 Understanding conflict preferences

Have you ever experienced conflict at work? You would be unusual if you said no to this question. Conflict may be low-grade (hassles between colleagues) or high-octane (shouting, bullying, people not speaking to each other). Conflict can occur between public servants and the users of their services (for example, some aspects of public order policing, or tensions within a mental hospital). It can occur between professions and between departments within the same organisation. Conflict can arise when a major change is proposed (e.g. the threat of hospital closure) or when elected politicians and local communities clash over the distribution of resources or the strategy being adopted to bring about change. Conflict seems to be everywhere.

Can conflict ever be constructive? While conflict is often thought of as being destructive to emotions, teamwork and performance, there can be situations where it may be productive. For example, conflict at work may lead to greater clarity about key values or goals. It can also help to ensure that leaders are not surrounded by people who always agree with them and who don’t challenge the assumptions they make or decisions they take.

But all this will depend on how an individual in a leadership role responds to conflict. This animation explores five typical approaches that leaders can adopt when dealing with conflict.

Transcript

In a famous study of managers, Thomas (1977) found five styles for handling conflict. He explored the idea that certain people may have preferences for particular ways of handling conflict. A preference does not mean that someone always uses that style or even thinks that it is the best style to use, but rather that they have a tendency to act in that way and will tend to use the other styles less or not at all.

So, what are those styles?

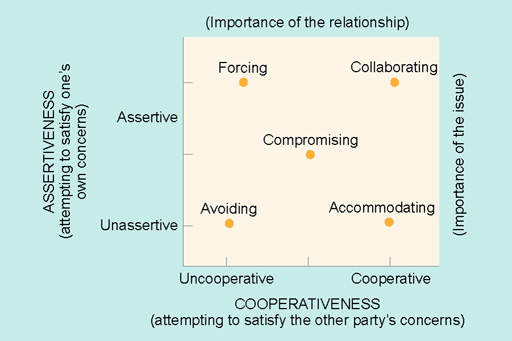

Two dimensions underpin conflict-handling styles.

The first dimension is how assertive the person is in pursuing their own interests in a conflict – from being very unassertive (not expressing one’s own needs or goals) to being very assertive (being clear and expressing one’s own needs and goals). Pause for a moment to think about that dimension. Does it make sense to you? Can you think of people in your workplace or team who are relatively unassertive? Can you think of others who are assertive?

The second dimension is how cooperative the person is in helping to satisfy the interests of the party they are in conflict with. Is the person motivated to help the other person achieve their goals or concerns, or is that not of interest to them? Again, pause for a moment to think about that dimension. Can you identify where people you are familiar with are placed within it?

The two dimensions of assertiveness and cooperation can be combined to provide a two-dimensional conflict-handling space as shown in Figure 4. The two dimensions provide the five conflict-handling preferences.

A situational approach

Having now examined personal preferences for conflict management, it is useful to examine what the situation might call for. Certain modes of handling conflict might take a leader out of their comfort zone but still be very useful for the situation in hand.

For example, you may initially think that an ‘avoiding’ mode might be problematic, in that it doesn’t immediately address the conflict problem and, if unattended, the conflict could get worse. However, sometimes avoidance is a wise strategy. For example, if you have two colleagues whose tempers have flared, then suggesting a break while they cool down before discussing the matter can be very beneficial. Also, most of us learn the hard way that responding immediately to an email that angers us generally ends in regrets. Better to leave the matter overnight where possible, when a reply might be calmer and more constructive.

The table below shows that conflict handling can be thought of in situational and not just personal preference terms. Each mode of conflict handling can have both advantages and disadvantages for conflict management and resolution. The effective professional is able to move out of their preference into assessing what would work for the situation or the relationship, and is able to think about the long term, not just the immediate short term. Issues, relationships and timing are key aspects which can help you make a choice according to the context you are in.

| Conflict-handling orientation | Appropriate situations |

|---|---|

| Competing |

|

| Collaborating |

|

| Compromising |

|

| Avoiding |

|

| Accommodating |

|