2.3 Implementing change and improvement

If you are already in a leadership role, you may have encountered a version of the ‘Plan Do Study Act’ (PDSA) cycle, or a variant of it. It provides a quality improvement model for guiding the continuous improvement of processes involved in providing public services.

The PDSA cycle was developed in the mid-twentieth century for use in improving quality in the manufacturing industry, but has since been adapted and widely used in many service sectors – for example, the health service. A leading health commentator has noted:

This model is not magic but it is probably the most useful single framework I have encountered in twenty years of my own work on quality improvement. It can guide teams, support reflection, and provide an outline for oversight and review; it is thoroughly portable, applying usefully in myriad contexts.

A model for planned change

The idea of planned organisational change has been developed since the mid-twentieth century in many sectors of industry and public services. Planned change requires leadership and management, particularly where it is large-scale, in order to shape activities towards planned outcomes.

Dunphy and Stace (1988) reviewed approaches to planned change, and noted that they can be either incremental or transformational and, on another dimension, may be undertaken in either a coercive or a participative way. Much organisational change, in both the private and the public sectors, has been shown to take place in somewhat autocratic ways. A study based on a survey in 2012 found that organisational change is viewed by managers across both the public and private sectors as not being well led:

In 2007, 45% thought that top management in their organisation was managing change well, but this declined to 30% in 2012. What we ask is that, when planning change, top management think more deeply about the effects of change on employees’ well-being, on their motivation, on their loyalty to the organisation and on the volume and pace of work that those affected by change will have to cope with.

Some key ideas about leading and managing planned organisational change – and for organisational development more generally – comes from the seminal work of social psychologist Kurt Lewin (1947). Lewin wanted to understand how changes in society can be brought about in a democratic rather than an autocratic manner. He undertook research into change in many social settings, and found that, where sufficient time is available, then educational methods rather than coercive ones are generally more effective in producing lasting change.

Many leaders in the public services come into contact with planned organisational change when a new reform is introduced. For example, a new policy or piece of legislation has to be implemented with which they may or may not agree (and colleagues may feel similarly). Or they may agree with the policy or change but hold views or have detailed evidence that the way the organisation or system currently works makes it difficult or unfeasible to implement high-level objectives or policy. Or a policy initiative may be announced in a ministerial speech but it is unclear how this is going to be enacted in practical terms.

Whatever the starting point for the change, managerial leaders and professionals have to begin planning how to undertake the policy implementation. In that planning, a leader may know about or become aware of various forms of ‘stuckness’ – a sense that the status quo is hard to change (this may be due to organisational culture and processes, in service users or in staff). Lewin (1947) recognised that organisations often fail to change because the forces opposing change are equal to the forces promoting or pressuring for change. So a canny leader needs to think about and analyse all the forces that are apparently keeping things as they are, and try to work out how to reduce these oppositional forces so that change can happen. Taking time to ‘diagnose’ the barriers to change can be half the work of organisational change.

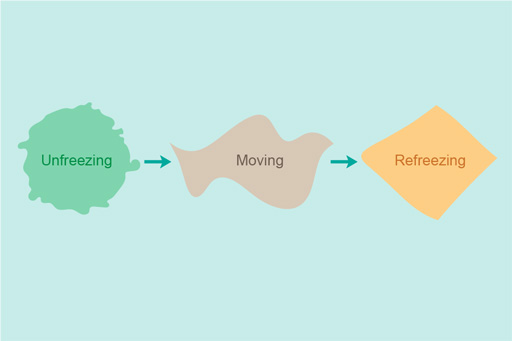

Lewin viewed the change process as made up of three steps or phases:

- Unfreezing: this is about reducing those forces that maintain the organisation’s or microsystem’s ways of working in its current form. Unfreezing may involve helping people to see the gap between where the organisation is and where it needs to be (a key role of leadership), or running workshops to analyse how things might be done better. Unfreezing is often an emotional as well as a rational process. Can the leader encourage and mobilise people for change? From the public value perspective, one might ask ‘Can the leader mobilise interest in the public value proposition and build the authorising environment?’

- Moving: this is about the actual change process itself. It involves practical changes to structures, processes, cultures, behaviours, working practices, HR systems and service provision arrangements. It is about leading the change and learning from interventions, fine-tuning changes where necessary. The changes may be in attitudes and behaviours as much as in practices, structures and processes.

- Refreezing: this step (often neglected in the heady rush of change) is concerned to stabilise the organisation and ensure that changes are sustained over time (so that things don’t drift back to old ways). This might include training, rehearsals or ensuring that other systems (e.g. promotions, appraisals) support rather than undermine the new behaviours and ways of working.

Many models of planned improvement or organisational change taken up by organisations, in industry and in public services, have a family resemblance to Lewin’s three-stage model. The ‘unfreezing’ stage is sometimes expressed rather differently, perhaps in terms of ‘defining the need for change’ or ‘identifying the objectives for change’, however the model overall remains a useful way of planning and implementing change.