3.1 Rich and poor?

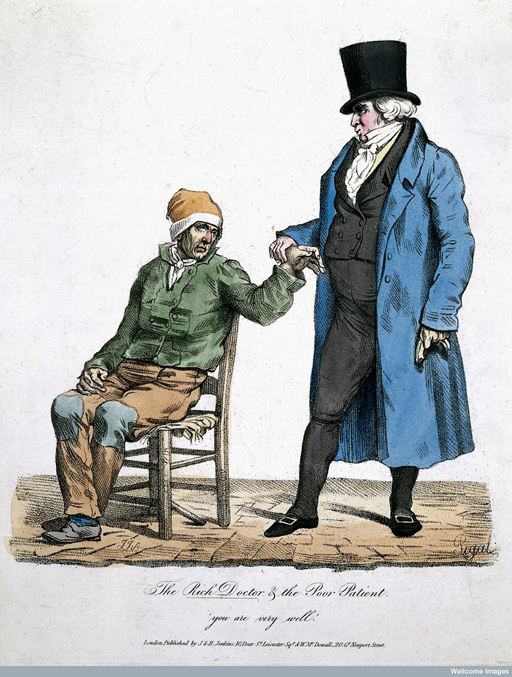

In Figure 8 you can see that, historically, there have been concerns about whether doctors are just out to make money. The ritual of measuring the pulse is used here to symbolise what the doctor does. In the companion image to this one, a doctor tells a healthy rich person that he needs treatment! But this is not only a modern concern. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder mentions the income of some famous doctors:

Erasistratus, a son of the daughter of Aristotle: for curing King Antiochus he received a hundred talents from King Ptolemy, his son … men like Cassius, Calpetanus, Arruntius and Rubrius: two hundred and fifty thousand sesterces were their annual incomes from the Emperors.

However, Galen – despite eventually becoming a doctor to the emperor – also knew about what peasants ate and drank, from meeting them on his extensive travels. He wrote that they would forage for blackberries and acorns, and store them in pits so that they could use them over the winter. If boiled and then baked, or ground up to make soup, acorns could be highly nutritious, Galen believed. He said that he had himself treated peasants for injuries, although he treated these with urine or excrement – materials he would not have used so readily for rich patients. He also treated domestic servants – who, like farm animals, were regarded as the master’s ‘property’ – and, in just three cases, slaves. He did not always charge fees, because he believed that a doctor should treat both rich and poor.

Galen was unusual, however. The suspicion that some doctors were charging whatever they thought the patient was wealthy enough, or desperate enough, to afford meant that some ancient writers argued that doctors were not really necessary at all. Self-help was the best medicine, they believed, and this line of thought has continued across history.