3.4 Knowing what’s normal

Celsus, who as you’ve seen wrote in the first century CE for an audience of educated Romans rather than for doctors, stated that: ‘But above all things everyone should be acquainted with the nature of his own body’ (On Medicine, book 1, ch. 3).

When Galen first met the emperor Marcus Aurelius, he emphasised that the normal state of the body should be understood in order to know what counts as ‘health’ for that individual. But do some features of the body, such as the pulse, always count as ‘healthy’ or ‘diseased’ regardless of the person in whom they occur? How far is health measured against a standard, or an ideal, and how far does it depend on what counts as healthy for a particular individual?

For example, missing pulse beats or having extra beats are today considered as something which can happen without the person being ill, but it can also be a sign of a more serious condition. Back in the second century CE, Galen had already argued that it could be one’s natural condition to miss pulse beats. In one example, a patient was a young man working as a steward and other doctors had noticed his pulse was missing beats. Galen, however, decided it was entirely normal for this young man (On Prognosis, 14).

This raises questions about who defined ‘normal’: who were the gatekeepers of health? For rich people the doctor could be a sort of personal trainer, working closely with them on all aspects of their diet, exercise, sleep patterns and so on – what Galen called the ‘non-naturals’ – and he would know their ‘normal state’. But poorer people would not have access to this level of care.

Instead, other ways of deciding on what was ‘normal’ were used. For example:

- The belief that ageing happened in periods of seven years, so that things were normal for one age group but not for others.

- Beliefs about the way that age group, temperament and climate interacted (e.g. what was normal for an old person dominated by yellow bile and living in a warm climate).

- The idea of one of the ‘four humours’ – blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile – dominating a person’s body and being their personal ‘normal’.

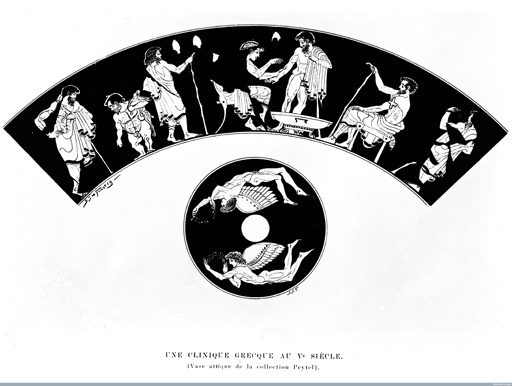

Were those with physical abnormalities defined as ‘healthy’, even if they were not considered to be ‘normal’? In Figure 11, a small container (called an aryballos, a flask with a globular body and narrow neck) from the fifth century BCE appears to show a doctor’s waiting room, with the doctor himself performing bloodletting on one patient.

One of the patients in the queue appears to have a growth disorder, perhaps achondroplasia, and is carrying a hare. Is this his fee for the doctor, or is he a servant or slave of one of the other patients? People with growth disorders could be servants, or craftsmen – even the god Hephaistos was represented as lame.