3.2 Facial reconstruction

In 1977, the skeleton of a man aged between 35 and 55 was discovered at Vergina in Greece in what is now known as ‘Tomb I’. The grave goods showed this was a wealthy person, as they included a gilded silver diadem, a helmet, a ceremonial shield and a cuirass (a type of armour). Two small ivory portrait heads were also discovered. Could this be the grave of Philip II, the father of Alexander the Great?

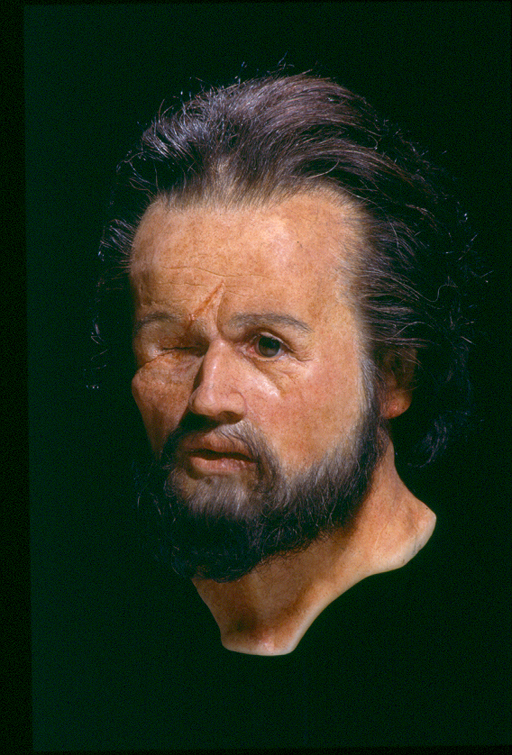

A team consisting of Jonathan Musgrave (anatomist), John Prag (archaeologist) and Richard Neave (medical illustrator) argued that it was. They used a literary source describing the injuries Philip sustained, including an arrow entering his right eye. A groove and a bump in the eye socket, they argued, showed that this skeleton had suffered such an injury and had subsequently healed.

However, the grave goods have now been dated to around 317 BCE, a generation after Philip was assassinated in 336 BCE. The groove and bump have been reinterpreted as normal features or damage to the skull after death. Scholars now emphasise the lack of other marks on the skeleton; this is surprising when other ancient authors describe damage to Philip’s collar bone and to the upper leg, which would have left him lame.

In another tomb on the same site, however, an adult male skeleton has a lance wound on the leg, which would match an injury Philip incurred in a battle in 339 BCE. Perhaps this one is Philip, and the other skeleton is that of Philip Arrhidaeus, the successor to Alexander, who was physically or mentally disabled and never fought in battle. The cuirass looks like the one Alexander the Great wore in a famous mosaic from Pompeii: did Philip Arrhidaeus inherit some of his older half-brother’s armour?

Activity 4

Can you find out how Philip Arrhidaeus died? Does the skeleton found show any sign of this?

Comment

While anatomical science can do much to show the faces of the people of the past, some details such as the shape of the lips or the colour of the eyes cannot be known, and at this point the reconstructor has to make his or her own decisions. The face needs to be believable. If an image of the deceased person survives – whether from a mosaic or from a portrait on their grave – it can be difficult not to be influenced by this when making a reconstruction from their skull.