3.3 Wine: the blood-making drink

Wine played a crucial role in ancient societies: it was the drink of choice of the Greeks and Romans. They drank it mixed with water, as drinking either water or wine on its own was considered unhealthy. Unmixed water could make people physically ill. Unmixed wine, for its part, could lead people to act in a crazy way: in Greek and Roman stories, cruel tyrants are often represented as drinkers of neat wine. It is now known that wine kills the bacteria found in untreated water, and that some ancient wines might have had a rather high alcohol content. The ancients, however, explained their mixing of the two drinks in terms of the key concept of ‘balance’ for health.

Figure 11, depicting the scene of a man vomiting, is represented on the tondo (the circular bottom) of a kylix, a Greek wine cup. On the sides on the cup you find representations of people at a symposium, a type of party where wine was consumed in large quantities. The image on the tondo is a reminder of what can happen when you have too much of a good thing.

The Greek medical author Mnesitheus wrote that wine was the greatest blessing, if used correctly:

It can be mixed with liquid drugs and it brings aid to the wounded. In daily intercourse, to those who mix and drink it moderately, it gives good cheer.

Mnesitheus is here referring to the use of wine in ancient wound dressings, and as a vehicle for ancient drugs. Today, you would explain these uses by making reference to the antibacterial properties of wine. Bacteria, however, were not known to the ancients. Instead, they argued that each type of wine had properties linked to its particular taste, smell, and colour. White wine, for instance, was considered especially moistening, and therefore helpful in drying conditions. Red (or ‘black’) wine, for its part, had ‘haematopoietic’ properties; that is, it could make blood.

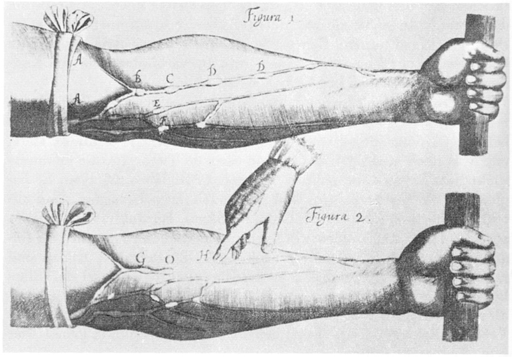

To understand this, you need to go back to ancient theories of digestion. The ancients believed that, after the food had been ground up in the stomach, some of it went to the liver, where it was transformed into blood. That blood then contributed to the good functioning of the body’s organs. The Greeks and Romans believed that the body constantly produced new blood – they did not know about the circulation of blood which William Harvey discovered in the early seventeenth century: Figure 12 shows one stage of his reasoning.

Some foods, they suggested, were particularly good at making blood and, of these, red wine was the best of all. No doubt the similarity in appearance between blood and wine influenced that belief. Galen wrote that:

Of all wines the red and thick are most suited for the production of blood, because they require little change before turning into it.

Black wine was recommended, for instance, to women who had heavy periods or lost much blood after birth. On the other hand, women who wanted to conceive were not advised to drink too much. Soranus writes that ‘the satiety due to heavy drinking hinders the attachment of the seed to the uterus’ (Gynecology, 1.38). Some wines were thought to have the power to make women infertile. The philosopher Theophrastus (fourth century BCE) writes that:

So at Heraclea in Arcadia they say there is a wine that makes men who drink it mad, and women sterile.

After the first days of her pregnancy, however, a woman was allowed to drink a little bit of weak wine before her meals.