2.1 Social economic conditions

Social and economic conditions in the 1930s were quite tough and there are three interesting aspects evident in how the appeal was managed and conducted.

The first aspect was: why did such a small claim in monetary terms (in today’s value it was worth only £27,400) end up in the highest appeal court? The answer to this seems to lie in Leechman’s doggedness in establishing a legal principle which reflected society’s needs and enabled the law to catch up with changes to economic interactions and social condition of the age, i.e. the beginnings of a modern consumer society. Another aspect in the same question was aiding poor litigants.

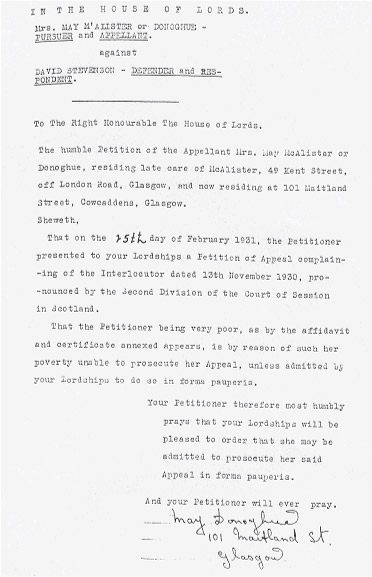

That leads to the question: how did May Donoghue afford the cost of an appeal all the way from Scotland to London? The journey from Scotland to London and into the House of Lords cannot have been an easy one. It must have appeared overwhelmingly expensive in terms of legal and other costs. Not only did she have to retain counsel who were willing to act without reward, but she had also to gain for herself the status of pauper, for otherwise she could not afford to pay the sum into the House of Lords needed as security for costs. Some assistance was offered by her legal team who agreed to work pro bono (without charge). It is fair to assume that one of their reasons for this was because they believed that law was not isolated from social history and needed to provide principles relevant to the burgeoning consumer age. Other assistance came in what we would now call legal aid. May Donoghue asked the House of Lords to waive costs as she was poor; to be declared a pauper (forma pauperis).

The progress of May Donoghue’s petition to be allowed to appear in forma pauperis is recorded in the House of Lords’ journal. It was supported by an affidavit in which she swore, ‘I am very poor. I am not worth five pounds in all the world’. Attached was a certificate of poverty signed by the minister and two elders of her church.

On 17 March 1931, her petition came from committee to the assembled House, consisting of the Lord Chancellor, Lord Sankey, the Duke of Wellington, two bishops, two marquises, twenty-four earls, sixteen viscounts, and eighty-eight barons, among them Lord Atkin of Aberdovey. In such distinguished company, May Donoghue was declared to be a pauper, with all the privileges attaching to that status before their Lordships’ House that she did not have to pay any costs.

The second aspect was: what prompted Leechman to take the chance of appealing outside Scotland? It might be that he believed he had better prospects of success there; in any event he had exhausted all avenues of appeal in Edinburgh. Of significance is the fact that the majority in the House of Lords were the three judges with non-English roots: Celtic majority. As already noted, Lord Atkin was born in Australia and educated in Wales. Lords MacMillan and Thankerton were Scots. The two minority judges who would have dismissed the grounds of appeal were impeccably English.

It may be just that Leechman was hoping that his chances of success would be greater with the stronger equity background of the judges in the House of Lords than in the Court of Sessions. Leechman believed that his father would have felt that Donoghue stood a better chance in London than she had in Edinburgh:

‘My father did not have such a high opinion of the Scottish judges of the time, even in the Appeal Court here. He felt that the judges in the House of Lords, being English and Scottish and using ‘equity’ as part of their base ... would be more equitable in their decision .’

Perversely, in fact, equity had little to do with the majority judgment. Lord Atkin’s neighbour principle was almost self-consciously placed to be in the line of existing authority. We can see this in his reasoning. After asking himself, ‘Who, then, in law is my neighbour?’, [emboldening added] he immediately states, ‘The answer seems to be ... ’; in using these words he is acknowledging there are judicial sources of authority for what should be the answer.

The third aspect was Mrs Donoghue’s legal status. May Donoghue is referred to in the 1932 Appeal Cases as ‘McAlister (or Donoghue) (Pauper)’. Other reports of her case refer to her as ‘May Donoghue’, and also ‘M’Alister’. She was born May McAllister, on 4 July, 1898, spent her whole life in the poorer districts of Glasgow, had a twelve-year marriage and four children, only one of whom, a son, survived infancy. Strangely, by the time of her death, on 19 March 1958, May chose to be known neither as Donoghue, nor McAlister, nor McAllister, nor M’Alister, nor indeed as May, but as ‘Mabel Hannah’, these being her mother’s names.