6.1 Close-in planets are easiest to find

One thing that really stands out about the transiting planets is how incredibly close most of them are to their parent stars. This isn’t just a fluke of the systems viewed by Kepler – the same is true of other transiting planets. Remember, HD 209458 b orbits its star in just three and a half Earth days.

The following video is an animated montage of the orbits of the 726 Kepler systems with multiple transiting planets. These systems with several planets are some of the most interesting that Kepler has discovered. The orbits of the Solar System planets are shown on the same scale with dashed lines, but the planets themselves aren’t to scale – there is a key showing how the sizes of the planets are represented. The colours represent the surface temperature of the planets based on the temperature and distance of their parent star.

It’s very easy to see that the Kepler exoplanets orbit much closer to their stars than the planets in the Solar System, resulting in extremely compact systems.

What’s going on here? Is our Solar System especially strange? No. There are probably plenty of stars out there with planets orbiting as far out as Jupiter or even Neptune. It’s just much harder to spot them when they transit.

Imagine a child playing hide and seek in the garden where there’s a decent-sized tree to hide behind. The child always chooses to stand directly behind the tree, instead of at a distance from the tree where the seeker could easily move a little bit to their left or right and see him or her.

The same thing happens for exoplanets in wide orbits. Unless the planet’s orbit is tilted by exactly the right amount, you will not see it transit, just as the child can’t successfully hide a long way behind the tree. But if the planet is in a tight orbit, like most of those found by Kepler, even if the system isn’t perfectly aligned there’s still a good chance it will transit. Of course, rather than hiding behind the star, the transiting planet is ‘hiding’ in front of the star from our point of view!

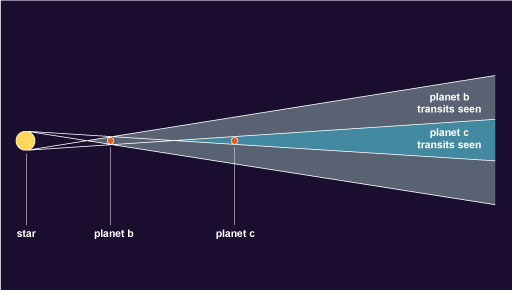

Figure 7 shows why close-in planets have a higher probability of transiting than planets which are further away from their star. Here we see that the range of angles from which we can observe the closely orbiting planet b transiting its star is much greater than the ranges of angles from which we observe transits for planet c in a wider orbit.

So, close-in planets are the most likely ones to transit, but there is also another reason why it’s easier to find close-in planets. Like HD 209458 b, hot Jupiters have incredibly short ‘years’, many taking fewer than five Earth days to orbit their parent stars. Because they complete their orbits quickly, they also transit more often than planets further away from their star. Both of these facts make it particularly easy to find close-in transiting planets. So, it is no surprise that most of the ones that have been found are close-in.