1.1 Modifying the antibiotic target

As you saw in Week 2, antibiotics are selectively toxic because they target structural features or cellular processes in the bacterial pathogen that are different or lacking in the host’s cells. Recall how penicillin and other related β-lactam antibiotics work by binding to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), preventing them from binding to their normal target, peptidoglycan. Or how trimethoprim prevents dihydrofolate reductase reacting with dihydrofolic acid.

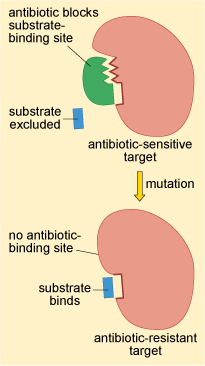

Changes to the structure of the target that prevent efficient antibiotic binding but still enable the target to carry out its normal function will confer antibiotic resistance (Figure 2).

This resistance strategy is widespread among bacteria. For example, the oxazolidinone class antibiotic linezolid disrupts bacterial growth by preventing the initiation of protein synthesis. The target of linezolid is the bacterial large (50S) ribosomal subunit. Changes to the 50S ribosomal subunit structure have been identified in clinical isolates of S. aureus and S. pneumoniae that are resistant to linezolid (Woodford and Ellington, 2007).

As you will see in Week 4, changes to the structure of antibiotic targets are often caused by genetic mutations. However, the structure of antibiotic targets can also be modified to prevent antibiotic binding by adding chemical groups. For example, resistance to linezolid can be caused by either genetic mutations (see Week 4) or the addition of chemical groups to the bacterial 50S ribosomal subunit, both of which prevent or reduce linezolid binding (Long et al., 2006).

You will return to look at how changes to the structure of penicillin-binding protein (PBP) contributes to resistance to cephalosporins in the case study at the end of this week.