4.1 Natural honey

Honey is a natural product that has been widely used in traditional medicine for centuries and is still used in modern medicine.

The antibacterial properties of honey were first reported by the Dutch scientist van Ketel in 1892 (Dustmann, 1979) and it is active against up to 60 types of bacteria. Table 1 summarises some of the clinically important bacteria mentioned in this course that honey has antibacterial activity against.

| Bacterial type | Clinical importance |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Hospital and community acquired infections |

| Vibrio cholerae | Cholera |

| Escherichia coli | Urinary tract infections, septicaemia, wound infections |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Wound and urinary infections |

Honey can be both bacteriostatic and bactericidal, depending on the concentration used. Its antibacterial activity is related to the following four properties.

- High

hydroscopicity Honey has a high sugar content and is

hydroscopic ; that is, it absorbs moisture from its environment. This causes bacteria to dehydrate in the presence of honey. - Acidity

Honey is acidic, with a pH between 3.2 and 4.5. At this acidic pH, many bacteria cannot grow.

- Hydrogen peroxide content

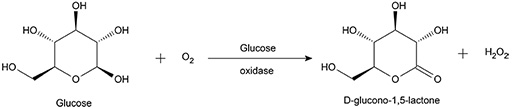

When it is diluted, honey produces the chemical hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) from glucose. This chemical reaction requires the enzyme glucose oxidase (Figure 10). H2O2 can kill bacterial cells.

- Phytochemical factors

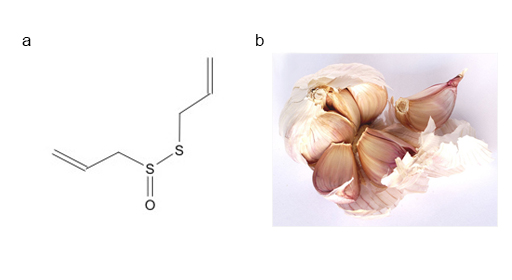

Honey contains a large number of phytochemicals which are chemicals produced by plants. Many phytochemicals have antibacterial properties. For example, allicin (Figure 10), produced by crushing garlic, has antibacterial activity against several bacterial pathogens, including MRSA and P. aeruginosa.