5 Flavours in alcoholic drinks

Alcoholic beverages come in a vast variety of flavours. Some of these are added deliberately to the drink (quite common for alcopops, fruit ciders and spirits), but in traditional drinks such as beer the flavours occur naturally, coming from the components – hops, grains, water and yeast. You first met these components of beer in Week 2. In this video, Danny Allwood describes some of the flavours associated with these components and where they come from.

Transcript

Within the malt, the yeasts and sugars interact producing lots of different chemicals that contribute to flavour and aroma. Brewing temperature and yeast strain strongly affect this. The main compounds are esters and phenols. In general, more esters are produced when the fermentation step is warmer. Ale yeast prefers warmer temperatures compared to lager yeast and produces compounds such as isoamyl acetate (sweet candy banana), ethyl octanoate (apple skins) and ethyl hexanoate (anise). Not all compounds smell good, though. Warm fermentations can result in ethyl acetate (acetone), which is commonly used in nail polish remover! Other flavours that are yeast dependent are 4-ethylphenol (an earthy aroma) and 4-vinyl guaiacol (cloves).

How the brewer treats the grains during the malting process leads to many of beer’s prominent flavours. Toasting the grains and the drying process have a large effect and also affect the colour. For example, darker grains smell like candy floss due to the presence of maltol.

During the toasting process the amino acids and sugars react together in a caramelisation called the Maillard reaction. Literally hundreds of compounds can result from this with the most common flavours and aromas including caramel, chocolate and coffee.

Hops are some of the most recognisable flavour providers. Bitter compounds such as the humulones – known as alpha acids – are present in the hop flower. The higher their levels, the more bitter the beer will be. Varieties of hop differ in content and therefore bitterness.

The classic hop smell comes primarily from essential oils in hops. You saw in Week 2 that, for a ‘hoppy’ beer, more hops are added at the end of the brewing process. The most common oils are alpha-caryophyllene and humulatriene. These two compounds create the key pine, citrus and sage-like aromas that hoppy beers are famous for.

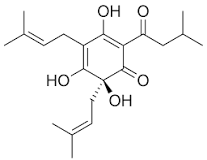

Consider the structure of humulone in Figure 7.

Is humulone likely to contribute to the taste or the smell of a beer?

Humulone is a large molecule with an RMM of 362.46 and as such is highly likely not to be volatile at room temperature. Therefore, it is more likely to contribute to taste rather than smell. Other smaller hops can be used to contribute to the smell of a beer.