2.1 Analysing ethanol by wet chemistry

As you learned in Week 1, the alcohol in alcoholic drinks is ethanol, and a molecule classes as an alcohol if its chemical structure includes the –OH functional group.

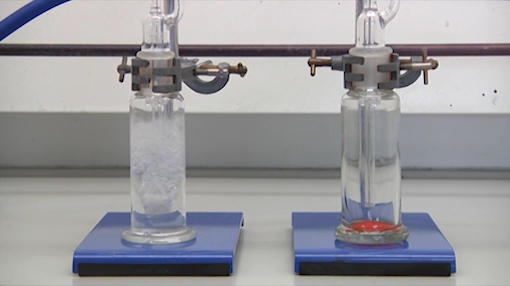

The following video demonstrates the chemistry used in roadside testing breathalysers. The breath of a test subject is exposed to an acidified purple solution of a substance known as potassium dichromate. If alcohol is present, the solution changes colour from orange to brown, and finally to green. The depth of the colour change can indicate how much alcohol is present although normally this is not sufficient for quantitative analysis – therefore, the secondary blood or urine test is required for law enforcement reasons.

Transcript

At this stage it is worth pointing out that sometimes this test does not give the results we would expect.

What do you think is meant by the term ‘false positive’?

A false positive arises when a positive result is obtained for a substance without this substance being present.

You may be familiar with the concept of drug testing in athletes. Sometimes, a test subject may test positive for a particular substance that the athlete denies ingesting. If the athlete is telling the truth and has not ingested the substance – but the substance is detected anyway – this is a false positive.

The same concept applies to alcohol testing. Several factors can cause false positives in breath tests for alcohol. These tests assume a particular ratio of blood alcohol to breath alcohol. If the concentration of alcohol in the mouth is artificially increased, this ratio is invalid. For example, recent use of mouthwash – which contains ethanol – can lead to false positives. Stomach gases brought up by belching will also contain alcohol. This means that, while these tests are generally qualitative (i.e. tell you whether or not alcohol is present), quantification (determining the exact amount of alcohol) is required by law.

The wet chemistry principle (that is, using a solution to test breath) described here is one very simple method of detecting alcohol and has been in use since 1938 when the first breathalyser – known as a ‘drunkometer’ – was produced. In recent years, however, this technology has been superseded by more advanced fuel cell technology, capable of accurate quantification of blood alcohol levels. These fuel cells systems are small, portable and highly accurate and consequently now represent the gold standard for roadside alcohol testing. However, the chemistry you have learned about here is still often used in commercial over-the-counter single-use test kits.