4.3 The disintegrating one: Kepler-1520 b

This is one of the most fascinating ‘planets’ discovered to date. When it was first discovered, Kepler-1520 b was known as KIC 12557548 b, and it took a while for it to be officially acknowledged as the 1520th planetary system named by the Kepler team. The reason for this is that it is very unusual, and no similar planet had ever been found previously, or even predicted.

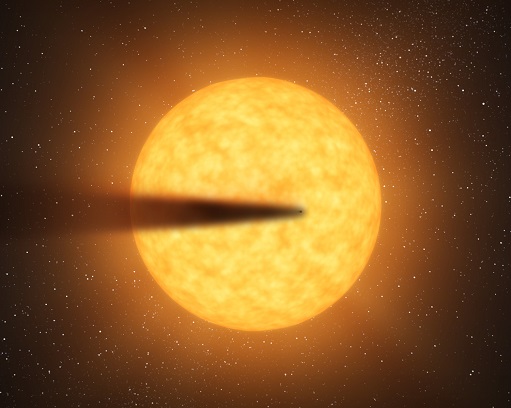

Kepler-1520 b is probably roughly the size of Mercury, and is likely to be a rocky planet, but the transits don’t look normal. The depths of the transits change a lot, which makes astronomers think they are caused by a cloud of dusty material around the planet. Different amounts of dust are seen each time the planet transits. Obviously a solid spherical planet cannot produce a changing transit depth because the cross-section of the planet would always be the same. Only something which changes size can change the amount of starlight being blocked, to create a transit depth which is different from one orbit to the next. This led astronomers to the dust-cloud explanation.

If the transits are caused by a transiting dust cloud, each individual transit should be very slightly deeper in blue light than red. This prediction comes about because dust scatters and blocks blue light far more effectively than it scatters and blocks red light. This same property causes sunlight to appear red at sunrise and sunset: at these times we see the Sun through a long, almost horizontal path through Earth’s atmosphere. The long path takes the light through a lot of dust, and many of the blue photons are scattered, while the red photons pass through. In 2015, researchers from The Open University detected the difference in depth between the red and blue transits of Kepler-1520 b, confirming the dust-cloud hypothesis.

Where this dust is expected to come from is quite remarkable. Kepler-1520 b’s proximity to its star would result in surface temperatures of around 2000 °C and astronomers believe the rocky surface facing the star is being turned directly to vapour, perhaps having already lost much of its original mass.

The compelling thing about Kepler-1520 b is the way the material from the planet is spread over a large distance. This may allow astronomers to use transmission spectroscopy to measure the composition of the disintegrating rocky surface. Unfortunately, Kepler-1520 b is very distant and so appears faint. It would be really exciting if we could find a similar disintegrating planet orbiting a bright, nearby star.