2.1 Literal or not? The role of genre

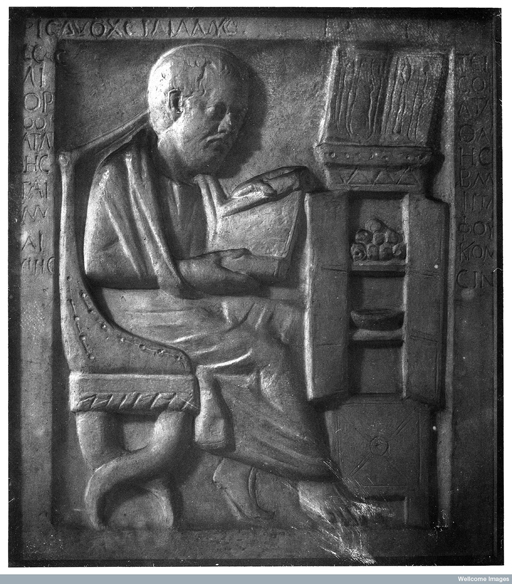

The range of material available when studying health in ancient societies is very wide. As you’ve already seen, it includes poetry and other forms of literature, but also texts written by doctors. In addition to literary evidence, there are also objects associated with health, and the physical remains – bones – of people who lived in the ancient world. You’ll be looking at these in more detail in future weeks.

One of the dangers of ancient source material is that it’s all too easy to take a text out of context. You need to be aware of who wrote it, when it was written, who the intended audience may have been, and the conventions of the genre in which it was written. Medical texts appear to be written for other doctors, but in the section ‘What is health? Ancient answers’, you encountered Celsus, who wrote on medicine but for a general audience of elite Romans.

When reading Galen, in particular, you also need to be aware that he likes to promote his own skills, so he presents other doctors as nowhere near as clever as he was. Things may have looked rather different from their point of view!

As you have seen in the sections ‘Health and the gods’, ‘What is health? Ancient answers’ and ‘Who is telling us this?’, poets and historians are also sources for ideas about health and illness. However, it can take some effort to work out how seriously to take what they say. For example, in Lucian’s Timon [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] you read that gold is very good at stopping bleeding, but this isn’t meant to be taken literally – Gnathon has been hit by Timon but is suggesting some money would make him feel a lot better about this. If you search for information on Lucian, you will find that his writings are satirical and intended to amuse. Lucian wrote at a similar time to the great doctor Galen.

Activity _unit1.2.2 Activity 7

Read the two epigrams from first century CE satirical writer, Martial, below then answer the questions that follow.

Until recently, Diaulus was a doctor; now he is an undertaker. He is still doing as an undertaker what he used to do as a doctor.

You are now a gladiator, although until recently you were an ophthalmologist. You did the same thing as a doctor that you do now as a gladiator.

There is some genuine unease being expressed here about doctors being bad for your health – after all, they were advocating drugs which could be poisonous – but this is used for humorous purposes. How do you react to the medical profession? Do jokes about doctors told today show similar fears to those expressed by Martial?

You’ll return to doctors and their attempts to restore health later in the course. Next, however, you’ll think about another approach common in ancient Greece and Rome – magic – and how separating ‘textual’ sources from ‘material culture’ may be problematic.