3 Keeping your finger on the pulse

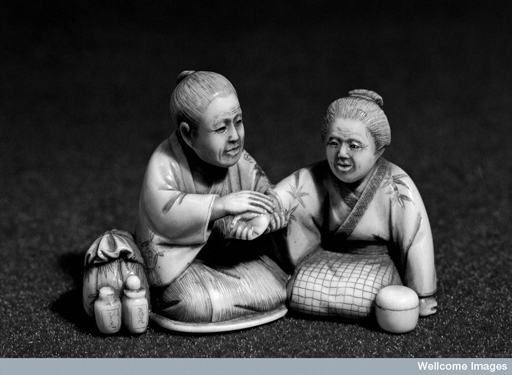

Taking the pulse is a very familiar part of modern Western medicine, but it’s also found in Eastern medicine, to the point that the hand on the wrist would become the mark of a doctor. Measuring the pulse was important in the ancient world too, but for different reasons.

You took your own pulse earlier, and here you will explore the different meanings that can be given to it. You will also encounter a disease of the past: lovesickness, which was briefly mentioned in Video 3.

The interest in the pulse goes back to Praxagoras of Cos in the fourth century BCE, but it is also mentioned in Egyptian medical papyri. The Papyrus Ebers states that it is possible to feel the heart by touching any limb, because vessels go out from the heart to the whole body. But the ancient pulse was about quality more than quantity. When ancient Greeks and Romans felt the pulse, they were sensitive to many aspects no longer considered: size, frequency, strength, speed, fullness, order, equality and rhythm.

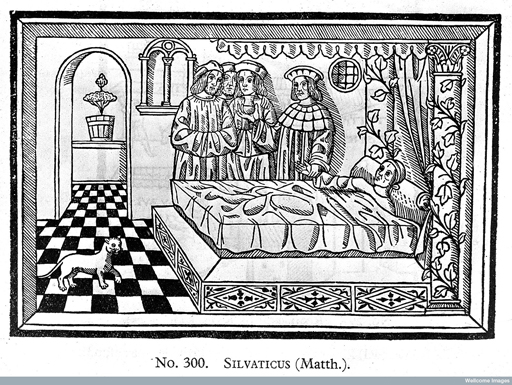

Galen wrote many books on the pulse and gave it a key role in prognosis because it showed how much vital force there was in the body. He even said he had diagnosed an intestinal tumour from measuring the pulse alone. He knew it was the arteries that moved, but he believed that these carried ‘air’ (aer), or ‘breath’ (pneuma), and he wondered if the movement he felt came from the arteries themselves or from the air in them. Most of his surviving treatises on the pulse were written in the 170s CE, where he recorded vivid descriptions, such as the ‘ant-like’ pulse and the ‘wave-like’, ‘worm-like’, or ‘mouse-tailed’ pulse; a ‘goat’s pulse’ is a short beat and then a stronger one. In Chinese medicine, similar distinctions are still made; for example the ‘unravelling’, ‘clay ball’, ‘soup fat’, or ‘darting shrimp’ pulse.

However, the awareness of the subtle differences in pulse was not something that could be learned simply by taking a watch or clock and counting; it had to be taught person-to-person. The focus on quality rather than quantity may therefore reveal something about knowledge and power. As a patient, you can’t easily know all these variations for yourself. Indeed, Galen claimed that not all doctors knew what they were doing either:

They consider a pulse that is not large to be large, or sometimes one that is not swift to be swift, or one that is not slow to be slow.

Activity _unit1.3.1 Activity 8

Measure your pulse again and this time concentrate on what animal it most resembles! Make a note of what you think below.