3 Doctors and excrement

In this section, you’ll see how some forms of ancient medicine used waste products, why, and how these would have affected people’s health.

Both urine and faeces – normally animal rather than human faeces – were used as medicines. Pliny the Elder praised a range of types of urine, including that of eunuchs which, he said, would work against any magical spell to prevent fertility. He describes a woman healer called Salpe who used urine to strengthen the eyes and also to cure sunburn; he adds that it could also remove ink blots. Human male urine was thought to cure gout, which is why, he claims, fullers never suffered from the condition – their work protected their health. Urine was also mixed with ash or soda and used for a range of skin conditions, including rashes and burns. He claims that:

Each person’s own urine, if it be proper for me to say so, does him the most good, if a dog-bite is immediately bathed in it, if it is applied on a sponge or wool to the quills of an urchin that are sticking in the flesh, or if ash kneaded with it is used to treat the bite of a mad dog, or a serpent’s bite.

In other situations it was not one’s own excrement that was of most use. Galen recommends the faeces of a child who had only consumed lupines (a member of the pea family), bread and wine. He also suggests that some people were willing to try a boy’s urine as a cure for eye disease – although most would not.

So, at least by the second century CE, there was clearly some unease among patients about these therapies. As you have already seen, people in the ancient world liked the smell of excrement no more than people do today. Galen insists that some animal dungs did not smell anywhere near as bad as people might have expected, but he also mentions a special odour-free dog dung, from a dog who has only been fed on bones. It was white, and good for throat complaints.

Scent therapy (both foul and perfumed) was used in ancient Greek medicine to treat women suffering from the ‘wandering womb’. If the womb was thought to have moved upwards in the body, foul smells would be put at the nose for the woman to sniff. These would repel the womb and make it move down. At the other end of the woman’s body, sweet smelling substances would entice the womb towards them.

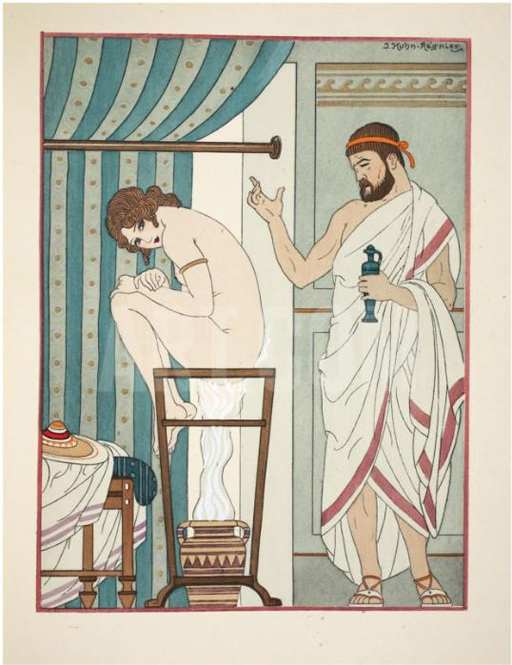

One more complex gynaecological process using scent therapy was fumigation. Women sat over a heated pot from which would rise up vapours of a particular scent. The vapours were thought to help move a woman’s womb into its correct position. In ancient Greece, the process would take place outdoors and would last for several days.

If the womb was thought to have turned around so that menstruation was not happening, the doctor was advised to apply substances thought to have a ‘warming’ effect. These were listed as follows:

cow’s dung, bull’s gall, myrrh, alum, all-heal juice, and anything else that is similar – apply a great amount of these, and evacuate downwards with laxative medications that do not provoke vomiting and are mild, in order that purging does not become excessive.

If a fumigation was performed, the pot would contain sweet-smelling herbs or spices, or animal substances, including, in one recipe, a puppy. This may have related to dogs having multiple births – litters – and the desire to encourage fertility in women too. In Week 5, you will look at the ideas surrounding conception and birth in ancient Greece and Rome.