2.1 Shaping the body from birth

Boys and girls were swaddled differently. Females had their breasts more tightly bound than males, and the area around the hips more loosely because this form was thought to be more attractive when they grew up:

She should then wrap one of the broader bandages circularly around the thorax, exerting an even pressure when swaddling males, but in females binding the parts at the breasts more tightly, yet keeping the region of the loins loose, for in women this form is more becoming.

This shape was also considered better for childbearing. Swaddling was practised for the first two months or so, until the body was considered ‘firm’. The first part to be released was the right hand, to encourage right-handedness. Babies were also unwrapped, bathed and ‘massaged and modelled’, the aim again being ‘so that imperceptibly that which is as yet not fully formed is shaped into its natural characteristics’ (Soranus, Gynecology, 2.32).

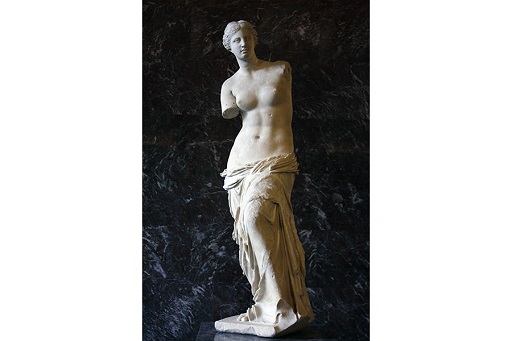

This shows that, even from childhood, a different ideal was expected for a woman’s body. Many Greek and Roman statues also depict women with a softer body than men, as seen in the Venus de Milo, a statue from the Hellenistic period (332–31 BCE), which has wider hips than male statues of a similar date.

The Roman goddess Venus was equivalent to the ancient Greek goddess Aphrodite. Another famous image of her was Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos, as described on the Perseus Project [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . You will see that it is now lost, but we know about it from Roman copies of the Greek original. Comparing these two images of Aphrodite/Venus with the representations of the male body you saw in Ancient ideals, you will notice that a different approach was taken to showing the genital organs.

As you discovered last week, women were thought to be ‘colder’ than men and so unable to transform their blood into semen. Notoriously, the philosopher Aristotle described women as ‘deformed males’. This meant not only that they had different body parts, but also that they were thought less likely to develop certain diseases:

Speaking generally, unless the menstrual discharge is suspended, women are not troubled by haemorrhoids or bleeding from the nose or any other such discharge, and if it happens that they are, then the evacuations fall off in quantity, which suggests that the substance secreted is being drawn off to the other discharges. Again, their blood vessels are not so prominent as those of males; and females are more neatly made and smoother than males, because the residue which goes to produce those characteristics in males is in females discharged together with the menstrual fluid.

So, although women’s bodies were different, they could also be healthier as a result.