Stage 1: Identify risk exposures

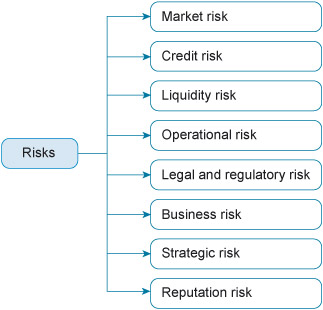

There is no single or definitive way to subdivide risk. The key point, however, is to ensure that the categorisation chosen covers each type of risk and is understood by all those using the results. The process should be tailored to the size of the organisation and the complexity of the environment it faces. A small organisation may only consider a small number of risks and deal with them in a much more informal way than a company like Unilever. For the time being, let us consider the full range of risks – including financial and other risks – which an organisation could face in running its business. One possible way of subdividing risk categories is depicted in Figure 3.

Financial risk

Financial risk is the focus of this free course and encompasses the top three risks in Figure 3. It refers to possible changes to the monetary value of wealth because of variations in cash balances (that is, liquidity) or in resources. Market risks include interest rate risk and foreign currency risk. You have already examined some aspects of financial risk management. You may have learned about gearing or leverage, which indicates the potential risk of future cash flows not being sufficient to service debt. Financial risk management does not take place in a vacuum; rather, it must be part of a larger, overall risk management strategy that takes into account non-financial risks. Managers have to balance the two types of risk. It may be advantageous, for example, for an organisation with a low level of non-financial risk to take on higher levels of financial risk to maximize its risk-return profile while the reverse is also true.

Operational risk

Operational risk is perhaps the most important and wide-ranging source of non-financial risk and accordingly is the only form of non-financial risk against which banks are explicitly required to hold capital. It embraces the risks arising from the failure of systems, controls or people. If key computer systems are not functioning, many organisations will have an impaired ability to deliver their goods and services, thereby adversely affecting earnings. If an organisation has an untalented or untrained workforce, its ability both to deliver current services and its capacity to engineer future development of the organisation is similarly impaired. Indeed, when looking at recent history there are several good examples of how operational failure has put organisations at a disadvantage relative to their competitors. Given the importance of this category of non-financial risk it is further explained in its own section later on.

Legal and regulatory risk

The second major category of non-financial risk arises from legal and regulatory forces which may cause financial losses to your organisation. It is of tremendous importance to certain sectors, such as banking, but much less important to some other industries. One example might be the recent changes in British tax laws that introduced a £2 billion windfall tax on oil companies: see Box 2.

Box 2 Statoil halts North Sea oil development over windfall tax

George Osborne is preparing to fend off a rebellion by the North Sea oil industry over his plan to impose a £2 billion tax on the sector.

The chancellor told the Treasury select committee that officials would contact Norwegian oil company Statoil, which has suspended development work on the new Mariner and Bressay fields to the south-east of Shetland while it studies the implications of the chancellor’s tax on the profitability of its operations.

Osborne’s £2 billion windfall tax on oil companies was a surprise measure in last week’s budget and will be used to offset a cut in fuel duty.

The North Sea oil industry is claiming that thousands of jobs are at risk and Statoil, which planned to operate from Aberdeen, said it would ‘pause and reflect’ before deciding whether to continue developing the fields which are due to come on stream from 2016/17.

Industry body Oil and Gas UK warned that the tax risked thousands of North Sea jobs. It called for immediate talks with the Treasury and an urgent meeting of Pilot, the government-sponsored oil and gas industry forum.

But Osborne defended the windfall tax to the MPs as ‘perfectly reasonable’ and insisted that Statoil had not yet cancelled any proposed investments. ‘They just want to talk to us about their investment plans,’ he said.

The chancellor, who came under fire from Labour MP John Mann for not knowing the exact amount of duty levied on a litre of petrol, insisted investment would increase despite the tax because of the surge in oil price.

The member companies of Oil and Gas UK – which include Shell and BP – met to discuss the new tax. Malcolm Webb, its chief executive, said the announcement had damaged trust in the government. It was now rerunning its survey of its members' investment and exploration plans. ‘The unexpected tax hike announced by the chancellor in last week’s budget looks to have been constructed hurriedly without rigorous analysis of its implications and has damaged investors' confidence in the UK as a stable destination for their capital,’ he said.

The Mariner and Bressay fields have estimated reserves of 640 million barrels. Bard Glad Pedersen, a Statoil spokesman, said the tax would have a ‘significant impact’ on the Mariner project. ‘We have to pause and reflect to evaluate what impact this will have and consider how to proceed after this. This is a project about to be developed. With this tax increase, there is a substantial impact.’

Peter Buchanan, chief executive of the Woking-based Valiant Petroleum, which specialises in smaller, marginal North Sea fields, said it would damage investment in the costlier fields, so North Sea production would decline faster.

‘The UK will import more oil and gas from parts of the world that contribute nothing to the Treasury. So increasing North Sea costs will have unintended adverse effects – it will reduce investment, put further pressure on oil and gas supply in the UK and ultimately could drive oil prices up further.’

The controversy is presenting significant political problems for the Liberal Democrats (Lib Dems) in the [UK] coalition government with reports that the party’s Members of Parliament in Scotland are planning to attack the proposal to protect their local party from a backlash by voters. The party is also struggling to defend seats around Aberdeen, the oil industry’s capital, against heavy pressure from the Scottish National party and Labour in campaigning for the 5 May Scottish parliamentary election. The latest opinion polls show the Liberal Democrats in Scotland are being very badly damaged by their links to the UK government, with their poll ratings 50 per cent down.

The city’s Press and Journal newspaper reports that two influential Lib Dem backbench MPs, Sir Robert Smith and Scottish party president Malcolm Bruce, are preparing to publicly criticise the plan. It has been defended by Michael Moore, the Lib Dem MP and Scottish secretary in the coalition cabinet, as the ‘right and fair thing to do’.

The Scottish National Party’s Treasury spokesperson at Westminster, Stewart Hosie, intensified the pressure by pressing Osborne to reconsider the tax during a Treasury select committee hearing in the Commons on Tuesday. Speaking after the meeting, Hosie said: ‘The tax changes announced by the Chancellor are totally ill-thought through and run the risk of diverting investment away from the North Sea. Statoil have already announced withdrawal from fields south of Shetland.

‘George Osborne must reconsider his plan before it endangers Scottish jobs further.’

Box 3 provides another example of legal risk, the recent fine of $308,000 that China imposed on Unilever for warning it might increase prices on some of its products.

Box 3 Unilever fined by China for price rise warning

Unilever and its rivals have been warning that higher commodity costs mean prices will have to rise

China has fined the consumer products giant Unilever $308,000 (£188,000) for warning it might increase prices on some of its products.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) said that comments by Unilever about possible price rises had created ‘market disorder’.

Both China and Unilever are struggling with higher commodity prices, including higher energy and food costs.

Unilever said it would abide by the agency’s decision.

The company told Chinese media some months ago that prices would have to rise, but Chinese officials said this had provoked panic buying.

The NDRC also said the warning had ‘intensified inflationary expectations among consumers’.

China, like other national governments, is battling to contain inflation, which is at a three-year high in the country.

Unilever, which sells a vast range of brands, including Cif cleaning products, PG Tips tea and Hellman’s mayonnaise, has been warning that it cannot keep absorbing higher raw material costs and will have to raise selling prices.

Its rivals, including Proctor & Gamble and Kraft, have also warned on prices.

All of them are increasingly looking to emerging markets, such as China, for growth.

While the amount of this fine is insignificant given Unilever’s size, the fact that it will not be allowed to raise prices in the huge Chinese market could have a substantial financial impact on the company.

Business risk

Business risk is another non-financial risk that managers must take into account. It encompasses various high-level risks that all organisations face, such as uncertainty about potential sales levels in different markets or the cost of producing goods or services for those markets (Crouhy et al., 2005). It is very difficult to accurately project these variables, particularly over longer time spans.

Strategic risk

A closely related type of risk, which many organisations include in the category of business risk, is strategic risk. This is the risk that arises from chosen strategies that are unsuccessful. One example might be BP’s strategy of partnering with the huge Russian state-owned oil company Rosneft to explore for oil together in the Arctic. This proposed strategy is being successfully opposed by one of BP’s major shareholders, as described in Box 4.

Box 4 BP’s Arctic future hangs in the balance

Among the throng of holidaymakers arriving in Cyprus at the end of this week was one of Russia’s most powerful businessmen.

Mikhail Fridman, however, was not there for the sunshine but to attend the board meeting of TNK-BP, a joint venture between BP and a group of Russian billionaires led by Mr Fridman.

Others attending included Tony Hayward, the UK oil major’s former chief executive; Lord Robertson, the former head of NATO; and Gerhard Schröeder, the former German chancellor.

The board meeting, although scheduled months ago, was anything but routine. It came after a momentous week. It was the first time BP met with its Russian partners since the collapse of the company’s proposed $16 billion share swap with Rosneft, the Russian state oil champion, on Monday night.

The swap, and an alliance to explore together in the Arctic, had been vigorously opposed by Alfa-Access-Renova (AAR), the vehicle through which Mr Fridman and his partners – Leonid Blavatnik and Viktor Vekselberg – hold their stake in TNK-BP.

Within days of the alliance being announced in January AAR claimed BP had broken the TNK-BP shareholder agreement. An international arbitration tribunal blocked the share swap following the protests.

Finally, after months of stalemate and with the original share swap agreement about to lapse at midnight on Monday, BP and Rosneft made a joint offer to buy out AAR from TNK-BP.

The three sides came tantalisingly close to a deal on Sunday that would have seen Mr Fridman and his partners receive about $32 billion for their 50 per cent stake in TNK-BP. The offer was a mix of cash and shares in BP.

Talks continued throughout Monday but no agreement could be reached. With Rosneft pushing for the share swap to be completed before a buy-out of AAR was concluded, the talks finally broke down.

On Tuesday, despite months of acrimonious wrangling, BP and AAR presented a united front, issuing a joint statement saying they would ‘intensify their efforts to ensure TNK-BP’s continued success following the lapse of the BP-Rosneft share swap transaction’.

Despite the warm words the collapse of the Rosneft alliance is a blow for Bob Dudley, BP’s new chief executive, who had presented it as a way for the company to rebuild itself after last year’s Gulf of Mexico spill and find a new area of growth in the Arctic.

Shareholders have not been impressed and expressed frustration with the way the deal had been handled. Mr Dudley, say some institutional investors, now needs to present a clear strategy for growth.

Whether it is all over remains to be seen – doing business in Russia is anything but a linear exercise. BP said earlier this week it continues to talk with Rosneft and AAR. Rosneft has seemingly blown hot and cold, signalling it is ready to talk to BP’s rivals such as ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell about teaming up in the Arctic but also announcing on Wednesday that talks with BP and AAR had yielded fresh proposals from BP on cooperation.

BP declined to comment on how the talks in Cyprus had progressed. Long-term industry observers believe a deal could still happen, noting that BP is keen to team up with Rosneft, while the Russian oil champion needs BP’s technical expertise to explore in the Arctic and is keen on the share swap – something that no other oil major is likely to agree to. What all of that means is that the cards are very much in Mr Fridman’s hands.

Reputation risk

The final category of non-financial risk faced by all organisations is reputational risk. Reputation has been defined as how stakeholders view the organisation (Schultz et al., 2000). A positive reputation can increase the loyalty of customers, employees and suppliers and can therefore provide significant financial or operational advantages. In contrast, though, a negative reputation can have a severely detrimental impact. To provide an example of this risk, Box 5 describes a situation which could impact negatively on Unilever’s reputation.

Box 5 Unilever and Nestlé accused over sustainable palm oil scheme

Plantation owners and pressure groups are calling on food producers such as Unilever and Nestlé to stop exploiting an environmental offset scheme to buy palm oil from unsustainable sources.

The $50 billion palm oil market keeps the world in soap, margarine, cakes and chocolate. Growing demand and spiralling prices, which have swung between $800 and $1,200 a tonne in the past 12 months, mean plantation owners are clearing forests to plant more palm trees.

To reverse this trend, the industry-backed Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil promotes practices for the increase of yields from existing palms, including use of fertilisers.

Plantations signing up to the standards are certified by the RSPO, and big European food producers have committed to using only certified sustainable palm oil by about 2015.

But most food producers buy GreenPalm certificates to fulfil their sustainability obligations while continuing to buy palm oil from less rigorously run plantations.

The certificate trading scheme, backed by the RSPO, offsets consumption against the production of an equivalent amount of sustainable oil.

Under the scheme, a buyer pays the current market $1,100 a tonne for ‘any old palm oil’ and about $3 a tonne to the sustainable seller of certificates, according to Alan Chaytor, executive director of New Britain Palm Oil, a sustainable producer.

‘Buyers have little idea where their oil comes from and the vast majority is from uncertified sources.’

Unilever, the biggest palm oil buyer, last year bought virtually all its sustainable oil via GreenPalm certificates.

The Anglo-Dutch maker of Flora margarine and Dove shampoo says the complex supply chain and the fact that it requires a variety of processed oils make it harder to buy sustainable oil physically.

Kellogg and Avon both recently agreed to buy GreenPalm certificates to cover 100 per cent of their palm oil usage.

But Nestlé, which meets half its sustainable palm oil commitment this way, is seeking to deal with vertically integrated companies that deliver segregated, sustainable oil.

United Biscuits says 70 per cent of its supply is segregated, traceable and certified.

This categorisation of three financial and five non-financial risks is commonly used but each organisation should develop its own typology to suit its industry and market position.