4.2 Intermediate forms

In essence, the argument about intermediate forms runs as follows. If whales evolved from a terrestrial ancestor through the accumulation of small differences over time, we should expect to find the fossils of a number of 'missing links', i.e. creatures with a mixture of terrestrial and aquatic characteristics. In fact, we might expect to find a succession of such animals, each a little bit more whale-like and a little bit less well adapted to life on land than its predecessor.

To make things more complicated, each of these intermediate forms must have been a fully working animal: it must have been able to breathe, to move about its environment, to feed itself and to reproduce. For a long time, biologists speculated about what these animals might have looked like. Surely at some point there must have been a creature that was at home on neither land nor sea, and so unable to compete with the animals already fully adapted to either habitat.

The problem of intermediate forms is by no means a new one. In The Origin of Species, published in 1859, Charles Darwin included a whole chapter on some of the difficulties facing his new theory. He started with the problem of intermediate forms:

Firstly, why, if species have descended from other species by insensibly fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms?

And a little later in the same chapter:

It has been asked by the opponents of such views as I hold, how, for instance, a land carnivorous animal could have been converted into one with aquatic habits; for how could the animal in its transitional state have subsisted?

Let's examine Darwin's questions one at a time. First, the scarcity of intermediate forms in the fossil record.

Question 6

What does the theory of 'punctuated equilibria' suggest about the chances of finding intermediate forms in the fossil record?

Answer

The theory suggests that we are more likely to find fossils of the animals that occupy the relatively stable periods (the 'equilibria') than we are to find the fossils of the animals that form part of the periods of rapid change, especially if that rapid change took place in small or isolated populations.

Now let's think about the nature of those animals.

Question 7

Can you think of any modern animals that are at home on land and in the water?

Answer

The TV programme contains a number of examples. Otters are wonderful swimmers and can chase and catch fish, but they also move about well enough to hunt on land [p. 186]. Seals and sea-lions are clearly most at home in the water, but they can still chase each other about on the breeding beaches. So it is possible to imagine an early ancestor of the whales leading a similarly amphibious existence.

Studies of the chemical make-up of proteins (particularly antibodies) in present-day species have shown that modern whales are closely related to the artiodactyls, a group of hoofed mammals that includes cows, sheep, deer and hippos. For some 100 years after the publication of The Origin of Species, all the known fossils of early cetaceans were either clearly terrestrial animals or primitive whales like those examined by Simpson. But recent finds have included the remains of creatures that might have had a more amphibious existence. These animals also lived in the Eocene (55 to 34 million years ago), in or around the warm, shallow waters of the Tethys Sea, an ancient ocean that stretched from modern Spain to Indonesia.

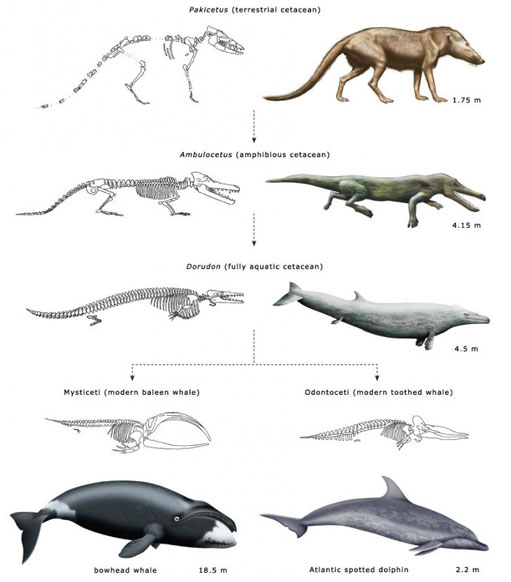

Figure 5 shows three representative animals in a postulated evolutionary sequence from an Eocene terrestrial ancestor to modern odontocetes and mysticetes.

Pakicetus is approximately 50 million years old. It lived by the side of shallow marine estuaries and was probably a wolf-sized ambush predator. It had long legs, an upright stance and may have spent much of its time running down small fish in the shallows.

Ambulocetus ('walking whale') is approximately 48 million years old, somewhere between Pakicetus and Dorudon. It was an amphibious animal with many of the characteristics we would expect in a transitional form. It could probably clamber about on land like a crocodile, but it was also a powerful swimmer, using its large feet and flexible spine like an otter. Intriguingly, it seems to have had a fluid-filled cavity linking its jaw and inner ear, similar to that found in modern dolphins (Figure 3), and it may have listened for the vibrations of approaching prey by resting its jaw on the ground - a strategy seen in today's crocodiles.

Dorudon is somewhere between 40 and 36 million years old. This animal lived in warm, shallow seas, where it fed on small fish and molluscs. It was about 4.5 m long and, like modern cetaceans, fully committed to a life in the water.

The Eocene was followed by the Oligocene (34 to 24 million years ago). The Tethys Sea disappeared as India ploughed into Asia, and the early whales found themselves having to live in deeper, colder waters. It didn't take them long, in evolutionary terms, to split into the two main lifestyles we see today. The toothed whales came to hunt fish and squid using high-frequency echolocation, while the baleen whales began to feed by filtering water, grew ever larger and sang their low-frequency songs across the oceans of the world.