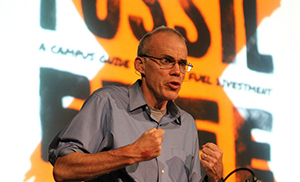

Bill McKibben is a founder of the grassroots climate campaign 350.org and the Schumann Distinguished Professor in Residence at Middlebury College in Vermont. He is a 2014 recipient of the Right Livelihood Prize, sometimes called the ‘alternative Nobel.’ He has written a dozen books about the environment, including his first, The End of Nature, published 25 years ago, and his most recent, Oil and Honey.

Bill McKibben is a founder of the grassroots climate campaign 350.org and the Schumann Distinguished Professor in Residence at Middlebury College in Vermont. He is a 2014 recipient of the Right Livelihood Prize, sometimes called the ‘alternative Nobel.’ He has written a dozen books about the environment, including his first, The End of Nature, published 25 years ago, and his most recent, Oil and Honey.

Transcript

Stories of Change Project

Bill McKibben interview

RH: = Roger Harrabin, Interviewer

BM: = Bill McKibben, environmentalist, author, leader of 350.org, participant

RH: Alright look, Bill, I’m doing some climate change documentaries and I’d like to record your thoughts for those. They are looking at climate science, climate politics and climate energy solutions. And then I’m also – separately but with a major overlap – doing some what the Open University call ‘legacy interviews’, long-form interviews, in which we talk to key players round the world on energy at some length about what got them interested in it and we probe solutions and problems a little more deeply. The idea is that they will remain on a special website with the Open University for scholars in the future, wondering, ‘What were they thinking about then?’ to look back at. If we can, can we start talking about the politics? You know, we see American politics unfolding in the bizarre way that it is: can you give me your estimation as to where you think the politics are on this in the States at the moment?

BM: Well, look, the politics in the States have always been fraught – of course, they’ve always been pretty fraught in most of the world. The problem always has been the power of the fossil fuel industry; it’s the biggest, richest industry on Earth and it’s headquartered in the United States – that’s where the biggest companies are located. They’ve been able to prevent serious action on climate change for a quarter century, but that resistance is beginning to break down, in the face of two things: 1) a powerful, growing movement demanding action. You know, we had 400,000 people in the streets of New York last September; we’ve got a massive divestment campaign going on around the world. It’s beginning to soften up the power of the fossil fuel industry. The other thing that’s going on – equally as important; the other half of the pincers – is the ever-falling price of solar panels. The fact that we’ve now got renewable, clean energy, pretty much at the same price as dirty energy, means that it’s no longer possible for these guys to pretend that the future isn’t coming. So I think that politics is probably better right now than it’s ever been, but that’s not good enough because the science is worse than it’s ever been. If we’re ever gonna catch up with physics, we’re gonna need a really concerted effort – one that we don’t yet have – to move rapidly, rapidly, rapidly toward renewable energy and to keep fossil fuel in the ground.

RH: It would be difficult to be optimistic about what’s happening in the States, though, wouldn’t it? You’ve had President Obama, who’s committed to this issue in his second term – and, theoretically, in his first term but actually in his second term. When she was Secretary of State, Hilary Clinton really wasn’t very greatly interested in climate change, so she’s one potential President, come this time next year, or come next year. Then we have her Republican opponent, whoever it might be and they seem obliged to cast doubt on the very science of climate change. And, in the meantime, you’ve got 66%, according to a recent survey, of Generation X in the USA not sure whether climate change is manmade or a problem or not.

BM: I don’t think the survey’s right: I think it’s extremely clear in most of the polling data that most Americans, millennials and everyone else, understand that climate change is a serious problem and are going to work on it. I don’t worry that much about who the particular politicians are who are in charge of things. If we build movements, (and we are building movements), the politics will move. But I’m not convinced they’ll move fast enough. I wrote the first book about climate change and I wrote it 25 years ago; we needed to get to work right then and there, if we were actually going to head off global warming. It’s too late now to do that, but we can keep it from getting worse than it has to get. That’ll depend on how powerfully we’re able to move the politics; that doesn’t mean obsessing about the particular personalities, or who’s gonna get elected President. The job of movements is to change the zeitgeist and if we can change the zeitgeist, then the policies will follow.

RH: What sort of a movement do you have in mind and do you have any historical comparisons?

BM: Well, I mean all movements, in some ways, are the same: they look to challenge the power of the status quo, which is often the power of money with a different kind of currency – passion, spirit, creativity. Sometimes we need to spend our bodies and go to jail. What’s different, perhaps, about this movement is that it’s the first one a) to be on a global scale and b) to arise in the time of social media. At 350.org, which we started seven years ago with nothing – myself and seven college undergraduates – has grown to the point where it now has held, we think, about 20,000 demonstrations in every country on Earth except North Korea. It’s helped spearhead the fastest-growing anti-corporate campaign, this fossil fuel divestment movement, that, maybe, there’s ever been, and is engaged in every continent, except Antarctica, in big fights to try and stop new extractive projects – fights that are going pretty darn well: from the tar sands of Canada to the big coal mines of Australia. And we’re just one part of this movement. There’s a … I think you would correctly call it a, sort of, fossil fuel resistance. One of the things that’s interesting about it is it has no great leader; there’s no Dr King for this movement. And that’s OK, I think – in fact, it may almost be a blessing in disguise, that we have a sprawling, protean movement ‘cause we’re up against an adversary, the fossil fuel industry, that’s sprawling and protean and everywhere itself. So we need to be in its face, on every continent, in every language, all over the place and this kind of spread out movement that we’ve got seems to be doing an increasingly good job of that.

RH: Just before we come back to the campaign, and I do want to come back to that, can you tell me why it’s called 350.org?

BM: So 350 is the most important number in the world, though no one knew it until 2008, when Jim Hanson at NASA, the world’s greatest climate scientist, put out a paper with his colleagues saying, ‘We now know enough about carbon to know how much is too much.’ Any value for carbon in the atmosphere greater than 350 parts per million is not, as he put it, ‘compatible with the planet on which civilisation developed or to which life on Earth is adapted.’ That’s strong language for a scientist to use and stronger still when you know that we’re already well past that, at about 400 parts per million and rising – about two parts per million per year. That’s why the Arctic melts, the ocean acidifies, California withers, you know. It’s a very grim but important number. The reason we chose it for this campaign that we were launching is not just because of its importance as a number; it’s also because we knew we needed to work around the world – I mean, they don’t call this ‘global warming’ for nothing – and we understood that Arabic numerals would cross linguistic boundaries better than phrases and slogans. So I think we’ve done our part to really inject that number into the planet’s information bloodstream and to good effect.

RH: But we’re already past your target, as you admit, we passed the target this year.

BM: We passed the target long (ago)

RH: Yeah, we passed 400 parts per million this year, we’re way past your target.

BM: Sure. We passed 350 long before we started 350.org. Our job, obviously, is to get back to it someday.

RH: OK. The other question I wanted to ask you before we went on is, what is that delightful bird in the background, or is it a bizarre effect of Twitter?

BM: No, no, I’m just sitting out on the porch here in the Vermont spring and there’s, I think, a hermit thrush in the background.

RH: Wonderful. OK, let me go back to the campaigning. You talked about the people using social media; you are arraigned against, as you admit, the most powerful firms, or the wealthiest firms (some of them) on the planet. Just for the upcoming election in the USA, the Koch brothers, whose wealth lies in coal and also oil, they’re putting in, I think, is it $900 million into the campaign? A lot of it will be to candidates who want to resist any change on the climate.

BM: Yes, between the two of them, the Koch brothers are the richest man on the planet <chuckles> and they’re gonna spend, yes, $900 million on the campaign, which is about twice what the Republican National Committee, or the Democratic National Committee, spent in the last federal election. So this would be Koch brothers, party of two. That’s why the Republican Congress constantly is trying to pass the Keystone Pipeline; I mean the Koch brothers are the single biggest lease-holders in the Alberta tar sands. It’s why our Kleinwood policy is so skewed. And one could just throw up one’s hands and walk away and give up; on the other hand, I think that we’re winning this fight, slowly but surely. It’s indicative that the Keystone Pipeline’s actually never gotten built; four years later, we’re still keeping 800,000 barrels a day of the dirtiest oil on Earth underground that investors are beginning to walk away from the tar sands, leaving billions upon billions of dollars on the table ‘cause they know that it’s no longer a good deal. I mean, just this week, the residents of Alberta tossed out their Conservative government and elected a left-leaning government that said they’d no longer lobby for the Keystone Pipeline. So we’re beginning to make progress and we’re doing it in the way that movements always have to. Given the physics of the situation, it should’ve been a no-brainer to stop the Keystone Pipeline. But we had to send more people to jail than over anything in this country in 30 years, the biggest civil disobedience action in three decades. Then we had to follow it up with constant, ceaseless campaigning; in every place that the President’s gone for three or four years, there have been people talking, holding signs about Keystone. And now, wherever Hilary Clinton goes to campaign, the same thing. So it’s a relentless effort, just like it’s a relentless effort in Australia to stop the new Galilee Basin coal mines; or a relentless effort across the UK to try and take on the people who want to frack it; or in Poland or in China or in all the other places where we work.

RH: OK, let me come back to that again, but you mentioned one thing there about people going to jail: this is a theme of yours. What is your interest in jail?

BM: Actually, I don’t think anybody should have to go to jail. I think it’s ridiculous, given that science has had a consensus on this issue for 25 years. But, and the lesson we learn from the civil rights movement and things is that, civil disobedience is one tool in the activist’s toolbox and that at moments when you need to underline the moral urgency of something, to draw attention to something that someone doesn’t know about, then sometimes civil disobedience is a good tool. When we started the civil disobedience campaign against the Keystone Pipeline, no one in this country had ever heard of it; by the time we were done, pretty much everybody had heard of it: it had become the iconic environmental fight of our time in the United States.

RH: And what were people arrested for?

BM: People were arrested for … well, I spent three days in Central Cell Block in DC for, I think the charge was ‘failure to yield’ <chuckles>. We were all sitting down in front of the gates of the White House.

RH: And you wouldn’t move on? And you were recommending – I saw you talk in the UK – I think you recommended that if you want to do anything about climate change, you should be willing to go to jail: you should plan to spend x amount of time in jail. Could you spell that out, your thoughts on that?

BM: The one thing I’ve tried to say, because I don’t take any of it lightly. I mean, when we were doing that campaign and when we do others, one of the things I try to say is: a) all our civil disobedience should be highly civil and b) I don’t think that young people should be the main cannon fodder here. If you’re 22 right now, in our economy, an arrest record might not be the best thing on your resume. One of the unmixed blessings of growing older is: past a certain point, what the hell are they going to do to you? And so it always pleases me when there’s a lot of grey beards like me showing up to do that part of the work. Young people are leading this climate fight all over the world, but this is one way that the rest of us can pitch in.

RH: Is that something you’ve actually noticed in the States, older people being willing to get arrested, get a criminal record?

BM: When we were doing the Keystone Pipeline protests, we didn’t ask people as they were getting arrested, ‘How old are you?’ ‘cause that would’ve been rude. But we did ask them – I think, cleverly – ‘Who was President when you were born?’

RH: <Laughs>

BM: The two biggest cohorts came from the FDR and the Truman administrations. So, yeah, people were stepping up and now I hear people occasionally say, ‘This is on my bucket list.’

RH: OK. On the bucket list to get arrested?

BM: Yes.

RH: <chuckles> Right, OK. And I think you were saying, when you came to the UK, somebody asked you at a public talk, ‘What can we do if we want to challenge climate change?’ And you said, I think it was, ‘Be willing to spend four days a month protesting and be willing to spend one of those days in jail.’ Something like that.

BM: I don’t remember saying that. I’ve never, sort of, run the math in that way in my mind.

RH: It may have been a flippant comment, but it’s one that stuck in my mind.

BM: I don’t remember it.

RH: And do you think we will be seeing older people moving into protest in the UK, in the way you say they were also in the USA?

BM: What do I know about the UK, you know? But I hope so and I think all over the place, people who are parents and grandparents are beginning to really think about the world that they’re leaving behind. Everybody does, as they get more towards the end of their lives or their careers. I was very moved to watch the amazing work that The Guardian has done in the last few months on climate change and, as Alan Rusbridger, the editor, has said, at some level, it’s because he’s getting ready to retire and thinking about the world in a different way. Rusbridger is already, probably, the greatest newspaper editor in the English-speaking world, but to see him go out with this amazing, crusading fight on climate change has been quite tonic for me.

RH: Before we just finish the politics bit, what hopes do you have of a global agreement on climate change in Paris? And do you think that our focus on those big global agreements is helpful, or do you think there are other factors at play now?

BM: What happens in Paris will be just one step along the way. I was pretty sure that Copenhagen was gonna be a debacle and the reason was that there was no movement at home to do anything about it. You know, there was no pressure on any of these governments. The UN by itself doesn’t do anything; it just reflects the politics and pressures of its member countries. So I imagine Paris will go a little better than Copenhagen, precisely because we have a movement now. But I imagine, also, that it won’t do anywhere near what needs to be done, and so no one should think that it’s going to be the end of the road.

RH: ‘cause there are many actors now, aren’t there? Businesses, some businesses and cities and other non-governmental organisations – there’s quite a broad range of actors. Much broader and, probably, deeper than there was at the time of Copenhagen, would you agree?

BM: Yeah, I think that’s probably true. I mean, there were a lot of different civil society people at Copenhagen. The difference is there’s now a kind of mass movement around these things: hundreds of thousands of people on the streets. The other difference is there’s more business interest on the side of change than there was. The fact that since Copenhagen, the price of a solar panel has dropped 75% continues every day to rewrite the rules of this game. It’s now entirely possible and plausible to move rapidly, rapidly, rapidly and relatively cheaply toward renewable energy. That makes the stalling tactics of the fossil fuel industry harder to get away with.

RH: Right, OK. Let me move onto the energy interview now. Can I start by asking you when you first became interested in energy?

BM: I was interested in these questions around climate beginning in the late 1980s. I had just written a long piece for the New Yorker magazine – I’m a writer by trade – about where everything in my apartment in New York came from. I followed all the, kind of, systems: the water system; where Consolidated Edison was getting its oil and things for the power system; on and on. And the impression that it left me with was that the world was a more physical place than I’d realised. I grew up in a suburb, like most Americans, and suburbs are, kind of, devices for hiding the operations of the planet, so I didn’t really have a sense of its physicality. And after that long, year-long piece I did, and I think it set me up well to be reading the early papers on climate change, I was struck by how vulnerable we were to these massive shifts that were coming. So I wrote, what became, the first book for a general audience on global warming: a book called The End of Nature that came out in 1989, which is now more than a quarter century on. That book, which was successful – I mean, it ended up in 20-some languages and on the best-seller list in some places – set the course of much of the rest of my life.

RH: And where did you go from there? Obviously you identified, at that point, that energy was going to be an issue, or the key issue.

BM: Where I went from there was for ten or fifteen years, writing and speaking about these questions on the theory that what was lacking, or the reason we weren’t taking action, was that the message hadn’t gotten through; that there wasn’t enough information out there. At a certain point, I realised that I was wrong about that: that we had won the argument, we just were losing the fight. And that’s ‘cause the fight was not about data and analysis; the fight, as fights usually are, was about power. So if we were going to have a chance, we would need to amass some power of our own to match the money power of the fossil fuel industry. So, at a certain point, I turned less to writing and more toward organising.

RH: And are you still a writer? Are you still making a living from writing, or are you getting funded from another source now?

BM: No, I’ve never been <chuckles>. I still make my living the old way, such as it is. I’ve never taken any money from 350.org or any other environmental group.

RH: But you’re now spending much of your life campaigning on energy issues.

BM: Yes, exactly right. Well, our job is to slow down, weaken the power of the fossil fuel industry; we’re trying to keep carbon in the ground. I wrote a piece a few years ago in Rolling Stone, that became their, I think, most widely-shared piece ever, which argued that the fossil fuel industry had about five times as much carbon in its reserves as any scientist said we could safely burn. Once you know that fact, then the fossil fuel industry … these companies are no longer normal companies; they’re rogue companies. And that’s led to the … if they carry out their business plan, if they dig up everything they’ve got and burn it, then, literally the planet tanks. So that’s led to this huge, ongoing divestment movement, which started in a few colleges in the US two or three years ago and now has spread to the point that the Church of England and Prince Charles and the Rockefeller family and on and on and on, have begun divesting. At the same time, we’re also working very hard against any of the big expansion plans of the fossil fuel industry; trying to, kind of, freeze their new infrastructures. So whether the fight’s about the tar sands in Alberta and the Keystone Pipeline, or about the Galilee Basin in Australia and the plans by the groups like Adani for massive new coal mines there, we fight everywhere we can because if that carbon escapes from underground and it’s burned then we can’t stabilise the planet’s climate ever.

RH: Scientists do make a distinction between the different fossil fuels, with coal being twice as dirty as gas and oil being somewhere in between. Calculation from University College London concluded that we had to leave in the ground 80% of the coal we had found, 50% of the gas and 30% of the oil, because we would continue to need oil to run cars in the interim, while we were trying to figure out good alternatives. Do you agree that the fossil fuels can be split in this way?

BM: Do I agree that they can be …?

RH: That they can be separated in this way and should be looked at distinctly, each on its own merits.

BM: Yeah, I think that argument’s increasingly outdated. I mean, one of the problems of having written about this 25 years ago was that there are plenty of times when I feel like I wanna say, ‘Oh, if only you’d listened to me then.’ 25 years ago, there was a pretty good calculus to be made for how you could use natural gas, maybe as a bridge fuel or something like that. But at this point, the Arctic’s melted; I mean we’re in a kind of emergency situation. So the idea of bridge fuels and things is less attractive than it was. We have to make the leap straight to renewables; the good news is they’re getting cheap so fast that that’s increasingly possible to contemplate. And I think that, yes, we’re gonna continue for a while to use some oil and some gas; the dumbest thing to do, however, would be to set up any new fossil fuel infrastructure – new pipelines, new wells, that kind of thing – because that locks you into using them for another forty years and we clearly don’t have forty years. So our job is to wind down all the fossil fuel just as fast as we can and replace it as fast as we can with sun and wind, which we’re capable, now, of doing.

RH: I was looking through presentations from Shell, recently, to its shareholders and Shell feel very strongly that they still need to get more oil and gas out of the ground, if they’re going to fulfil the demand as envisaged in the International Energy Agency scenario that would lead us, probably, to a two degree temperature rise. So, in other words, even if we stick to the two degrees, we’re still going to need to find more oil and gas.

BM: We’ve got five times as much oil and gas already in our reserves, as would take us past two degrees. Shell may be the single most irresponsible company in the world. They looked at the melting Arctic, which scientists had said would melt if we continued to burn hydrocarbons – and indeed it did. And Shell looked at that and instead of saying, ‘Hmm, maybe we should go into the energy business instead of the fossil fuel business, maybe we should start investing in solar’, they looked at the melting Arctic and they said, ‘This will make it easier for us to drill for yet more oil.’ And they were first in line for the permits to do it. They define irresponsibility - man, one hopes that we can head off players like that.

RH: You could also argue that they define realism. If you look at the trend scenarios for energy, you see that at the moment, renewables are the tiniest fraction. So I was talking to Saleemul Huq, who you may know, from Bangladesh, yesterday, and he said that in Bangladesh, he was lauding the virtues of solar power for poor people in rural Bangladesh. But solar power is still just 1 or 2% of Bangladesh’s total energy need; the rest of it is coming from natural gas and Bangladesh is drilling its own natural gas. There is no way that we can fuel the world on renewables at the moment.

BM: I think that that’s actually wrong. In this country, for instance, half the new electric capacity last year, or close to it, comes from solar power. It’s still a small number, but the trend is enormously fast and if we build on it quickly then we can do it – and there’s no reason not to.

RH: OK, let me stop you there because that’s the trend for new investment; that doesn’t take into account all the investment that we already have that’s going to last the decades.

BM: Yes, yes. Well no one’s talking about shutting down … I mean, there’s no possible way to shut down everything tomorrow that we’re already doing. But new investment’s the interesting question, right? And if we’re installing 50% of new capacity for our renewables then it’s just a matter of years before we’re getting to 50% of generation from renewables, as stuff retires. It’s not that we can’t do this, if we really wanted to. If we took on a, kind of, World War II scale approach, where we converted all our efforts to doing it, I don’t think anyone doubts that we could do it. The question is how fast we’ll do it, how much effort we’ll put into it: and I would argue that in a world where your major physical features are now beginning to break; where the Arctic is melting; where the ocean is rapidly acidifying; where we’re seeing enormous increases in drought and flood, I think I’d argue for more effort than you’re arguing for.

RH: You talked about the divestment campaign; what is the aim of that campaign? Is it to bankrupt the firms or just to bankrupt them morally?

BM: I think, more the latter, although <chuckles> I’ve been impressed with how quickly it’s accomplishing both. Our original aim was to politically bankrupt them; to make it harder for them to hold such sway over this debate. But, you know what? The analysis has spread so fast. I mean, three years ago, it was me in the Rolling Stone; now it’s the World Bank and the IEA and the Bank of England and everybody else saying, ‘You gotta be really careful now, investing in these companies. It’s a big carbon bubble, there are gonna be lots of stranded assets.’ It’s beginning to –

RH: To be fair, they’re saying, ‘It might be a carbon bubble.’

BM: Excuse me?

RH: To be fair, they’re saying not that it is a carbon bubble, but that there might be the possibility of a carbon bubble, which is different.

BM: Well, I mean, I think that there’s very little argument that we have far more carbon than we can burn. That’s what Mark Carney said not long ago; that’s what Deutsche Bank said in the last few months. I mean, everybody recognises it; it clearly is a carbon problem. If we burn it all then the temperature goes up way more than the world has agreed to do; that’s, sort of, the definition of a bubble, right?

RH: Fund managers in the City that I’ve spoken to, (most of them, not all), believe that Shell and companies like Shell have 30 years, probably, left before they really have to start tightening down on their fossil fuel operations. And they’re willing to continue investing, certainly, for a decade or two before they have to start thinking about pulling funds out.

BM: People always think they’re gonna time the market and get out at the peak, but I think that they’re probably wrong. I mean, our students and people were saying, ‘Get out of coal’ three and four years ago, as we started this divestment campaign. Anybody who listened made a lot of money as a result because coal stocks have tanked. Now gas and oil stocks look like they’re poised to do the same.

RH: Well, coal is down, what, two thirds, isn’t it? Something like that, 60% coal stocks have dropped. You think that’s because of divestment, or do you think it’s because of slowing global demand.

BM: No, no. I think it’s because the argument that environmental campaigners have been making is sinking in: we can’t burn this stuff. So there’s now a big movement around the world to stop doing it. The Chinese don’t want to burn anymore; America doesn’t want to burn anymore; it’s filthy stuff. And we’re beginning to recognise the same thing about oil and gas. Ask Shell how much fun they’re having, trying to get their rigs out of the Port of Seattle and up into the Arctic. There’s protests everywhere these guys turn and there will be more of it all the time.

RH: When you say ‘more of it’, it is very difficult to protest in the Arctic.

BM: Yeah, it’s difficult to drill in the Arctic, too. The point is that if you’re gonna drill in the Arctic, you need to use a place like Seattle as your home port and next week, there’ll be thousands of people in kayaks, blocking Shell’s effort to move their rig out to sea. The Mayor of Seattle has called on the Port of Seattle to revoke Shell’s lease on their facility there. These guys are pariahs and we’ve got them on the run in as many places as we can.

RH: Well, you say they’re pariahs; they’re still very close to governments and still … they’re very heavily funded.

BM: Oh yes, they’ve still got lots of money. Rich people will always have friends; the good news about politicians is they’ll be bought by whoever comes up with the next sum of money and as the solar industry grows and the wind industry grows, they’re beginning to have some of that same political sway too.

RH: Some would argue that the solar industry in the USA have bought too much influence previously and you had that horrendous collapse, didn’t you, which was very embarrassing.

BM: That doesn’t strike me as particularly … I mean, the Republicans tried to make a big deal out of Solyndra, that company in California. But, in fact, solar jobs have been increasing left and right: the Solyndra factory now belongs to Solar City, the fastest-growing solar installer in the country; last week, Elon Musk announced his new battery storage plan. So many people ordered it in the first week that they’re now, apparently, planning to increase the size of the factory they have under construction in Nevada. I think it’s pretty clear which direction history’s gone.

RH: You see, that’s really curious, isn’t it? Because Elon Musk, who you mentioned, who founded the Tesla electric sports car and is something of a visionary in this field, he’s brought out this battery pack, a home battery pack, where you can store energy that you’d create from your solar power or your wind power, or maybe buy energy cheaply when it’s off-peak and store it for when it’s on peak. But if you look at the maths on that, it really doesn’t add up: you’d have to keep this unit for years and years to make any money back off it, if at all.

BM: People seem to disagree with you and seem to be lining up to buy it. You know, there’s some of us, an increasing number of people, who actually also care about the fate of the planet when we do the maths, you know? So we’re eager for making the transition to solar energy. And now that it’s at grid parity, across most of the United States, indeed, most of the world, there’s more and more people who wanna figure out how to do it. The good thing about these solar batteries is they’re a way to tell the utilities to screw off, if they won’t let people do it and, well, I think that’s increasingly gonna happen. 3,500 bucks – which is what they’re charging – is a much lower price point than people expected and well within the realm of possibility. I mean, people spend $3,500 on a good bicycle.

RH: Goodness, you must get a good bicycle for that much. But this may be playing into the narrative that you’re weaving, in that people will look at the cost of the battery and they’ll think, ‘Well, actually, I can afford this; I wanna be an early adopter; I wanna be part of this revolution, I’m gonna buy it.’ And, if enough people do buy it and then the production increases then the price will come down and it will be affordable to more people. But the early market, in the solar industry, was driven largely by government subsidies; in a case like this one, it may be driven by a well-wishing public.

BM: Look, anybody who bets against technology in these ways is nuts. I mean, the first iPhone was expensive too; if you bought Apple stock, you were a smart man.

RH: Do you have Apple stock? <chuckles>

BM: I don’t.

RH: <chuckles> Do you have Tesla stock or Solar City stock?

BM: No, I’m a writer, remember?

RH: You’re not such a smart man?

BM: I’m a writer; I’m not a rich man.

RH: Let me ask you about other things. If you manage to get pressure put increasingly on fossil fuels, people who agree with you and are also worried about climate change are worried that you will just drive those big companies into biofuels and they will be looking to try to get energy from biomass, which will be as harmful, in some ways, as getting it from coal.

BM: Yeah, I have complete faith in the ability of the fossil fuel companies to make an endless number of stupid decisions. But, sooner or later, they’re gonna notice that the world wants to head toward distributed energy; toward sun and wind. I mean, price of solar panels has fallen 98% in the last forty years. What does that tell you? Solar power is the only resource we’ve got that gets cheaper and cheaper the more of it you use. So I think that eventually, these guys will get a clue and do the right thing. They could’ve owned this industry, if they’d gotten smart ten or fifteen years ago; but they didn’t and so they’re gonna be playing catch up.

RH: But I notice you keep harking back to solar. Now, solar is a powerful force in California and can be across the southern belt of the USA but here in England, it’s still a long way from grid parity. Where you are, in the north-eastern states, I guess it’s still a long way from grid parity, too; and by the time you get up to Canada or large other parts of the world, solar is really, absolutely not ready yet and won’t be ready for maybe, what, ten, fifteen, twenty years, depending on how near the poles you are.

BM: It may not be ready but I’m talking to you off the solar panels on my roof right now; that’s what’s powering the computer we’re talking over. Look, if you live in an igloo in the North Pole, it’s not gonna be your choice of power, at least during the winter. But the good news is that with the nice high latitudes, we’ve got winds blowing all over the place; the Danes generated 40% of their power from wind last year. Now that’s just another form of solar energy, in a way; you know, the contrasts between hot and cold, that’s what causes the wind to blow. So I’m not worried; it looks to me like northern Europe is leading the world in figuring out these things. The Germans and the Scandinavians are the gold standard.

RH: If you look at developing countries, say like Bangladesh, for instance, they are installing a lot of solar but they’re still trying to get as much gas out of the ground as they can. They need it to fuel their garment industry which, at the moment, cannot be fuelled by solar power and if you want to create jobs that are going to pull people out of poverty, we’re still going to need fossil fuels for a long time, are we not?

BM: I don’t think so. I think that we’ll quickly find that everything you can do with gas, you can do with renewable energy. And I think … I mean, I watched the first solar panel go up … I didn’t watch it go up; I saw the first solar panel in Bangladesh, fifteen, twenty years ago. I was up on the roof of a little school, where it had been installed, with the guy who installed it; they’re now putting up sixty or seventy thousand a month. The people who are doing it are great heroes and, frankly, I’m less concerned about the garment entrepreneurs in Bangladesh than about the people there and around the world, who have lived in real energy poverty, who’ve never had light. The quick spread of solar power around the developing world over the last two or three years is one of the great human rights stories of our time and it’s beautiful to see. And it’s something that didn’t happen with fossil energy, you know? 200 years of fossil energy did very little for people in rural Bangladesh, sub-Saharan Africa, most of India; ten years of solar energy is doing an immense amount more.

RH: Can I suggest, though, that that statement, it may look a little naïve to some people because you have said, rightly, that rural people in Bangladesh are being massively helped by solar power and you don’t care much about the garment entrepreneurs. But it’s the garment entrepreneurs who are creating jobs so those people can earn money and pull themselves out of poverty.

BM: I think 85% of Bangladesh, or 80%, still lives in rural areas –

RH: It’s just under 50% now.

BM: – and I think the good news is that as we begin to provide solar power and things to those communities, people will no longer need to flee them in order to go live in a shack on the edge of the capital city. That’s been the prevailing pattern around the developing world for a long time, in part because those were the only places where you could electric hook-up, get any kind of power. But that’s no longer true and there’s a real possibility for equitable development across the developing world: It is already very good news for all kinds of people. Now, of course, Bangladesh has deeper problems: they relate to the fact that most of the country is low on the Bay of Bengal, it’s a river delta, the Brahmaputra river delta, and they’re going to be badly, badly affected by rising sea level. They already are: there’s lots of internal displacement of people already, from places where the salt front is making agriculture impossible. So, yet another good reason why people in Bangladesh, I think, are very happy to see the spread of renewable energy.

RH: There’ll be some people in developing countries who’ll balk at what you’re saying and they will reply to you, ‘Look, I don’t want to live in a rural area in a hut with a solar panel that allows me to have a black and white television for an hour and a half a day and a telephone and a lightbulb for my children to study. I want to live in town; I want to live in an air-conditioned apartment with plenty of energy; I want to have a good job; I want to buy consumer stuff and I want to be like you.’

BM: That’s important for people to pursue the things that are important to them and that will continue, no matter what I say and what I do. The thing is: we have to obey the rules of physics. And if we don’t, the people who will be affected first and foremost are the most vulnerable people on the planet and that’s why people all over the world have joined this climate effort. I told you a minute ago that 350.org has organised in every country on Earth except North Korea; we can go look at the pictures from around the world – including places like Bangladesh, where great civil society advocates are joined in this climate fight ‘cause they know who’s lives are first on the line.

RH: Bill, before we finish, I want to ask you a question. You kind of answered this already, but I wonder if me asking you the question formally will elicit a different answer. It’s basically: how optimistic are you about what’s happening now?

BM: I’m optimistic that there’s a big movement that’s arisen; I’m pessimistic that we waited a long time to get it started because the science is very grim. In general, I try not to spend too much time worrying about whether we’re winning or losing; just get up in the morning and see what we can do to push us further along.

RH: You didn’t really answer that. I mean, it sounds to me, from that and your previous answer that, actually, you really are rather pessimistic that we won’t be able to make the energy transition in time.

BM: I wouldn’t say that that’s correct. We’re not going to stop global warming; we waited too late for that. We can still keep it from getting entirely out of control, but only if we act rapidly and dramatically – and we’ve got a narrow window, the scientists tell us, and that window is closing fast. We have this ‘deus ex machina’ at the last minute, the rapid fall in the price of renewable energy; that can be a game-changer, but only if we can stand up to the power of the fossil fuel industry. We shall see.

RH: You also have a rapid fall in the cost of oil and gas.

BM: That’s <chuckles> … well, we shall see. I mean, we have great volatility in the price of oil and gas. It’s nothing like … if you look at the curves of price for oil and gas, go stack ‘em up against what’s been happening with fossil fuel; you’ll see oil and gas bounce up and down, year after year, all over the place. What you see with renewable energy is a steady, steady, steady downward fall. And the reason, if you think about it, is clear: these aren’t fuels in the same way that oil and gas are. They’re technologies, right? I mean, the fuel’s free – the sun comes up every day. What we’re buying is technology, and technology gets better year after year after year. It doesn’t get scarcer or harder to find; just the opposite.

RH: So that does offer grounds for optimism, that last statement.

BM: That part of it cheers me up.

RH: OK <chuckles> glad we’ve done that a little. So Bill McKibben, thank you very much for your time.

BM: Thank you, Roger.

<End of interview>

Rate and Review

Rate this audio

Review this audio

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Audio reviews