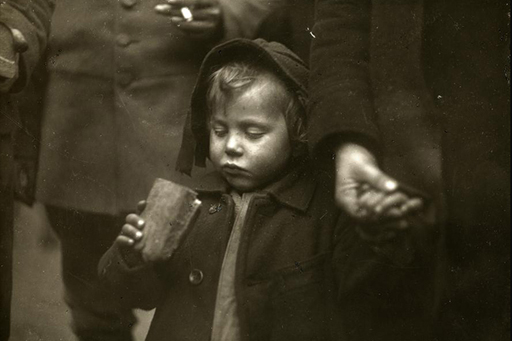

2.2.2 Hunger: a child’s perspective

Look at this account of the experience of hunger. Although it is a fictional account, it is likely to have been autobiographical to some extent. The author and his character share the same year of birth (1902), and would therefore have been too young to fight in the war, but old enough to experience and remember the deprivations on the home front.

‘This is going to be a hard winter,’ sighed my mother on one of those days, as Kathinka put the meal on the table. The meal consisted of a couple of slices of fat-free sausage, daintily cut-up turnips, which were held together by a thin sauce, and three potatoes per person. The bread could well have been used to make models of small men. It was like clay. We sat waiting, almost praying, in front of this meal. Perhaps, we thought, it would change miraculously to match our desires. While I was opening my napkin apathetically and lethargically – for we had been eating the same thing almost daily for months – my mother put her hand on the back of my neck, ran her hand almost fearfully through my hair and said softly and indistinctly: ‘I can’t do anything about it … tomorrow perhaps I can get a couple of eggs and some meat … don’t be so sad … perhaps I can also get some white flour …’ She wept. ‘But mother,’ I lied, ‘this tastes very good, although of course the other things would be even better.’ I picked up my spoon and dug enthusiastically into the pale turnips. Then Kathinka, who has been allowed to eat at our table since the beginning of the war, stopped me, gave me a reproaching look, and folded her hands. We sat stiffly in the chairs, and as a company of new recruits marched through the street to the firing ranges, singing songs as ordered, I prayed loudly and defiantly, ‘Dear Lord Jesus, be our guest and bless what you have given us.’ From the bread plate the slogan of the year glowed in red letters: ‘Better war-bread than no bread.’

Then we bowed our heads quietly over the meal. Kathinka gave me her potatoes; my mother gave me two slices of sausage. Afterwards I had to lie down so the meal would settle. Kathinka, however, was asked to go next Sunday to her parents, who live on a farm in Upper Franconia, and to get some butter. My mother gave her one of her prettiest blouses and, for her old father who liked to read books, three volumes of Felix Dahn’s The Struggle for Rome. ‘Thank you,’ said Kathinka and wiped her hands with joy on her apron, the pocket of which was embroidered with a small black, red and white flag. ‘Ha, I’ll bring butter rolls back – they won’t catch me. . .!’ She meant the military police, who for the last month have been posted at the train stations, checking every arriving passenger for forbidden foodstuffs. We trusted Kathinka, because we knew where she hid the butter rolls. In her woolen bloomers. The shamelessness of the war had not yet reached the point where the police were allowed to search there.

Hunger, as well as the fear of enemy action, made for traumatic childhood experiences. We think of shell shock affecting soldiers, but even children could be affected by trauma. It is likely that we will never know the long-term effects of such suffering, and of course, for many it was only to be exacerbated by the even more horrific treatment of civilians and soldiers in the Second World War.