Systems approaches for practice

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 2:06 AM

Systems approaches for practice

Introduction

Welcome to the second part of the course Strategic planning: systems thinking in practice.

As in the first part of the course, this part looks at five systems approaches. These approaches are:

- system dynamics (SD)

- viable system model (VSM)

- strategic options development and analysis (SODA)

- soft systems methodology (SSM)

- critical systems heuristics (CSH)

Part 1 focused on systems thinking in relation to situations of interest, people (agents, actors, stakholders, practitioners), and systems as conceptual tools for enacting strategy. Part 2 focuses more on the practice side of systems thinking in practice, whilst always keeping in mind the continual interplay between thinking and practice.

Note: This short Openlearn course is not teaching how to use the five systems approaches listed above. The course gives a general introduction to the approaches and what they may have to offer in support of systems thinking in practice.

Learning outcomes

After completing this part of the course, you should be able to:

describe three practical dimensions of using systems tools and ideas

describe examples of conventional entrapments associated with reductionism and dogmatism

describe examples of potential entrapments associated with systems thinking claims towards holism and pluralism

understand relevance of systems and strategy for managing uncertainty in changing situations

appreciate the range of systems approaches for managing uncertainty in changing situations.

1 Thinking strategically in practice

There are several ways of classifying different systems approaches. Some like to classify them according to the particular situation which they are deemed to be appropriate. So, for example, according to some, soft systems approaches are seen as relevant to situations of multiple perspectives whereas, say, critical systems heuristics is deemed more relevant to situations of conflict. Others have classified approaches according to particular communities of practice to which practitioners of the systems approaches align themselves (e.g. cybernetics, learning systems, complexity theory etc.). In this part of the course, we appreciate more the actual and potentially adaptive use of systems tools from different approaches depending on the users’ experience as part of the context of use.

Activity 1 The practice of systems thinking

Read section 1.2.7 (‘Our own perspective’) from Introducing Systems Approaches, along with a quick recap on sections 1.2.8 and 1.2.9 (from the first part of this course, which briefly describe the five systems approaches). Make notes on the three practical dimensions of using systems thinking and their alignment with three core ideas of systems thinking in practice:

- understanding inter-relationships

- engaging with multiple perspectives

- reflecting on boundary judgements.

With respect to Figure 1.4 in the reading, describe a key feature of importance in using any systems approach with respect to addressing the three dimensions? How might this differ with the conventional idea that some systems approaches are suited to only some situations?

Discussion

The dimensions outlined by Checkland include methodology, situation, and users. These can be re-ordered in terms of

- understanding inter-relationships (‘situation’)

- engaging with multiple perspectives (‘users’)

- reflecting on boundary judgements (‘methodology’).

Figure 1.4 illustrates the importance of addressing all three dimensions in any practical application of systems thinking tools.This challenges the conventional idea of ‘contingency’ – that particular approaches are suited only for particular situations.

Systems practice challenges the practitioner to be inventive with the use of any set of tools associated with any particular approach in order to ensure that inter-relationships are understood, multiple perspectives are engaged, and that the limitations of being holistic (inclusive of all inter-relationships) and being pluralistic (engaging with all perspectives impartially) are properly taken in to account. The emphasis is not on the tools (systems tools or other tools) being ‘used’, but rather the ‘user’ of the tools.

Activity 2 The systems practitioner

Read the Systems Approaches Epilogue up until (and not including) 7.2.4 ‘Recognising the Possibility of Entrapment’. Make notes on different practitioner communities and their role and significance in developing systems practice. To what extent might these communities relate to your understanding of disciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity?

Discussion

The notes that you write can vary in relation to what you find particularly insightful. Generally, the idea is promoted that systems approaches ought not to be regarded as fetishised or reified (concrete) tools (e.g. like a ‘hammer’ or ‘computer’) but rather as conceptual constructs open to continual adaptation and development according to the practitioner. A key way of ensuring such development is through conversations or interactions with other practitioners. These may be practitioners belonging to one particular discipline (e.g. defined as either a specialist discipline of, say, the viable systems model (VSM) users, or wider discipline of Systems thinking). They may alternatively be practitioners from different disciplines or traditions of practice (e.g. other systems traditions or other academic disciplines altogether like economics, engineering or performing arts). These two ideas fit in with ideas of disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity respectively. The notion of ‘transdisciplinarity’ is not really dealt with in the chapter. My notion of transdisciplinarity is an interaction with wider society. This can be interpreted in terms of ‘other communities of practice’ as described in the third level of interaction, but it might also involve more general public or civic society – individuals in a capacity not recognised as a ‘community of practice’.

Any process of thinking strategically, whether formalised through schools of approaches or otherwise manifest through personal experience and practice, comprises valuable skills and competences. Such value should not be ignored or denied. Rather, systems thinking in practice must be seen as a complementary skill to existing skill sets, including your own. Moreover, it is a skill increasingly acknowledged among professional strategists themselves (see Box 1).

Box 1 Systems and strategic skills

Extracts from a guide on strategy skills presented by the UK government's Strategy Unit.

A key component of thinking strategically is recognising that issues do not exist in isolation. Holding a mechanistic view of policies as levers that have a focused and direct impact on a situation, without considering the wider implications of an intervention, can be short sighted and potentially disastrous. Strategic thinking requires the interrelated nature of circumstances to be recognised up front rather than relying on a post hoc screening to identify unintended consequences and impacts.

…

Systems thinking is both a mindset and particular set of tools for identifying and mapping the interrelated nature and complexity of real world situations. It encourages explicit recognition of causes and effects, drivers and impacts, and in so doing helps anticipate the effect a policy intervention is likely to have on variables or issues of interest. Furthermore, the processes of applying systems thinking to a situation is a way of bringing to light the different assumptions held by stakeholders or team members about the way the world works.

…

Systems thinking is particularly powerful for understanding dynamic complexity, which stems from the relationships between factors in a system. A dynamically complex system cannot simply be broken down into pieces in the same way as a structurally complex system, which derives its complexity simply from the sheer number of factors involved. Where structural complexity can be modelled and managed using databases and spreadsheets, dynamic complexity needs a more organic approach to understand the complex web of influences that often results in various forms of feedback loops. Such loops add a time dimension to system complexity and often magnify or dampen the intended effect of an action in a non-obvious manner.

Jeanne Liedtka, a leading academic in the field of strategic thinking, identifies a number of attributes or competencies of strategic thinking in practice. First and foremost in her view is the attribute of having a systems perspective that she describes as follows:

A strategic thinker has a mental model of the complete end-to-end system of value creation, his or her own role in it, and an understanding of the competencies it contains.

Taking a systems perspective is a distinctive competence in itself, which is a competence that I refer to as systems practice.

Liedtka’s description of a systems perspective for strategic thinking suggests three features of systems practice:

- a core exercise in modelling involving a process of value creation

- reflection on practitioner's role in the situation

- appreciation of relevant competencies.

I'll expand on each of these in relation to strategy making.

1.1 Modelling and value creation

The idea of a mental model enables a clear distinction between situations and systems. A key point in systems practice is not to confuse systems with situations. Do not confuse the map for the territory, to use an important adage from Alfred Korzybski (Korzybski, 1933).

Systems practice involves thinking in terms of purposeful abstraction. Conceptual constructs are abstracted from real-world, complex situations to improve the situation. An example of this can be provided in illustrating a model of strategy making.

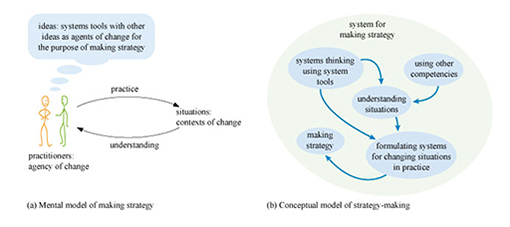

The two models in Figure 1 illustrate the three constituent parts of making strategy (situations, practitioners and ideas). They are depicted in Figure 1 both as a simple mental model and as a conceptual model in the formal sense of the term used by what is called soft systems methodology. In both cases they are systems models because they depict activity serving some explicit purpose.

The two models are drawn from my perspective. Neither provide complete pictures of reality but in their different ways they enable me to convey important components of strategy making. The models themselves can then be used as a baseline for debate on how to make strategy. Each of the five systems approaches referred to in this course use models of one kind or another. They are not physical tools like a hammer or a can opener, but conceptual tools. Figure 1 (a) illustrates this at two levels. At a first-order level, you can see the tools illustrated as part of individual thought bubbles. The tools making up systems approaches are themselves models used for understanding and practising in the real world. At a second-order level, the whole diagrammatic representation of Figure 1 (a) itself represents, as the caption says, a model.

This way of considering a situation will stop you feeling trapped and frees us from a sense of impotence. You will be less inclined to say ‘the system is against me’ and ‘how can I beat the system’. Instead, I hope you will see systems as opportunities for designing better strategy.

1.2 Reflective practice

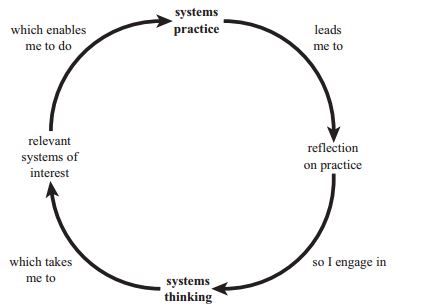

Thinking strategically is theory informed by action. Thinking and practice are of course integral. But it is this integral relationship between thinking and practice that demarcates systems practice as a distinct competence. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship in terms of a learning cycle using a simple causal-loop diagram.

1.3 Competencies

Box 2 continues from the listing of competencies in Box 1.

Box 2 Systems competencies 2: systems practice

- Systems practice is reflective practice.

- Part of the skill of an aware systems practitioner is their ability to use systems thinking as part of a process of learning (by them or with others), in which the outcome is some improvement to a situation of concern.

- The particular form of learning at the core of systems practice is concerned with enabling effective action among stakeholders in complex situations. This involves collaborative action or social learning.

- Systems practice recognises the significance of making boundary judgements and continually exploring purpose.

- In addition to problem solving, systems practice can help identify what other problems might be relevant to a situation.

- Systems practice is a transdisciplinary skill used to complement and support an existing skill set from a single discipline.

- Part of the transdisciplinary skill is in using a systems literacy that helps facilitate interdisciplinarity.

- Systems practice draws on, but is different from, systems science or complexity science in that it attends to judgements on boundaries and values as much as judgement on facts.

Activity 3 Systems thinking in practice in other skill sets

From the list of competencies in Box 2 make a note of any competencies that you feel represent an existing strength in your own practice and one that is less strong.

A further competence might be described in terms of a willingness to be disturbed. Thinking differently can be experienced as discomforting in that it often requires disturbing conventional ways of thinking and doing. This is related to recognising traps and thinking of strategies for avoiding them and/or escaping from them.

The next section describes three common traps and gives a rationale for the selection of the five systems approaches chosen as a means of avoiding or springing the traps.

2 Practical traps in systems thinking

The five systems approaches were chosen on the basis of their respective emphasis on purpose and usefulness.

What you read for Activity 1 refers to three general purposes that can be summarised:

- understanding interrelationships and interdependencies

- practice in engaging with different perspectives

- responsibly questioning judgements on interrelationships and perspectives.

Activity 4 Traps in systems thinking

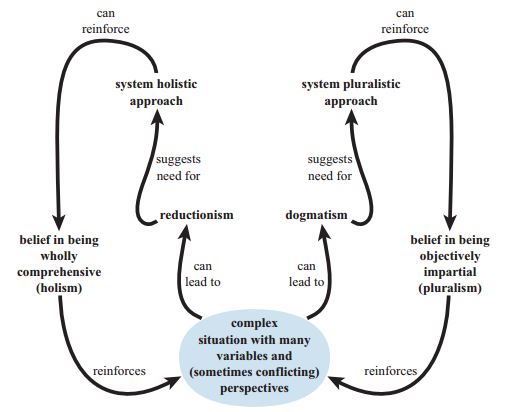

Read 7.2.4 ‘Recognising the possibility of entrapment’ from the Systems Approaches Epilogue. How might the traps of reductionism, dogmatism, holism and pluralism be associated with the three purposes of systems thinking in practice?

Discussion

The traps can be aligned with the three purposes of systems thinking in practice as follows:

- understanding interrelationships and interdependencies: associated with trap of reductionism

- practice in engaging with different perspectives: associated with trap of dogmatism

- responsibly questioning judgements on interrelationships and perspectives: associated with traps of holism and pluralism.

The following section explains these alignments more fully. Items 1-3 above can be understood in terms of three purposes associated with purposeful systems thinking in practice –

- understanding inter-relationships

- engaging with multiple perspectives

- reflecting on boundary judgements.

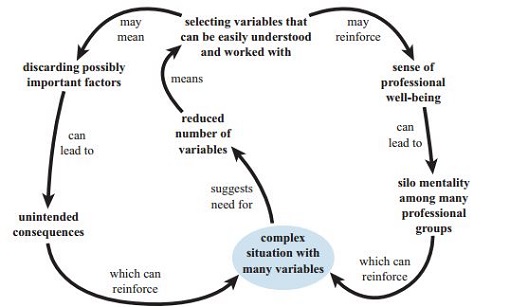

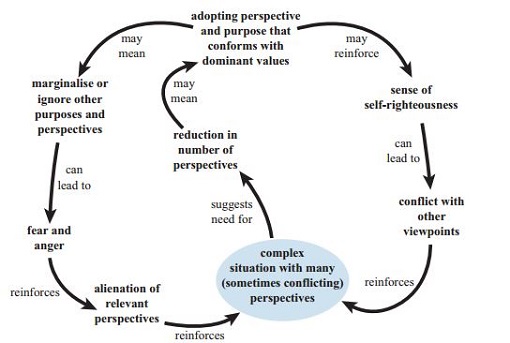

Purposes 1 and 2 are associated with avoiding traps in conventional thinking. Purpose 3 is associated with avoiding a corollary trap in systems thinking. Each trap can be illustrated in terms of a causal-loop diagram. The three traps are represented below in conjunction with particular systems approaches used for avoiding and/or escaping from, or springing, the trap.

2.1 Trap 1 Dealing with reductionism

This is a concern about having a limited understanding of the situation because of silo thinking or narrow-mindedness.

The two approaches that address this in particular are system dynamics and the viable system model. Figure 3 illustrates the trap of reductionism

2.2 Trap 2 Dealing with dogmatism

This is a concern about restrictive practice through ignoring other perspectives of the situation.

The two approaches that address this issue in particular are strategic options development and analysis and soft systems methodology. Figure 4 illustrates the trap of dogmatism

2.3 Trap 3 Dealing with holism and pluralism

This is a concern about avoiding responsibility for boundary judgements made in systems thinking.

The tool that addresses this issue in particular is critical systems heuristics. Figure 5 illustrates the trap of holism and pluralism.

Each of the five approaches attends to all three traps and associated purposes. However, while each of the five deals with all three purposes, historically each was born out of a particular emphasis on one over the other two purposes. This does not suppose that any one approach only fulfils one purpose to the exclusion of the other two. The maturing of each approach over 25 years has meant that they have evolved to serve all three purposes.

Your exploration of the usefulness of each systems approach in the Tools stream will be undertaken in an area of practice that is both appealing to you and rich enough in terms of comprising many variables and contrasting perspectives.

3 Your area of practice

Thinking strategically always begins with the situation – context matters. To appreciate the value of each approach it is helpful to have situations embedded in:

- a common area of practice for applying any or all five approaches

- an area of practice that is of particular interest to you.

In applying systems thinking in practice, you may like to choose an area of practice that prompts situations of interest to you.

Five important criteria can help you to choose an appropriate area of practice:

- interest – the area must invite your own personal interest, which may usefully be an existing or aspiring professional area of practice, but which may alternatively be an area of more general interest

- practice – the area must have an associated central element of practical change, signalled by an adverb or doing word such as control, regulation, management, or reduction

- scope – don't define an area of practice too narrowly (perhaps use ‘immigration control’ rather than ‘checking passports’), and try to include different hierarchical levels (practice may have local, national or international ramifications, or practice may include elements of policy planning, management planning and operational planning)

- perspectives – the area of practice should invite different viewpoints

- uncertainty – there should be significant possibilities of unforeseen change.

Some possible areas of practice are listed below, chosen because I think they match the criteria, but feel free to consider others that may be of more interest to you.

- local community service support

- financial regulation

- drugs control

- education assessments

- health support for the elderly

- reduction in child mortality

- poverty reduction

- ecological sustainable development.

Activity 5 Developing ideas for an area of practice

Nominate an area of practice, indicating why it is of interest, and then choose one situation of interest associated with the area of practice, and suggest two systems of interest that might be developed in order to strategically improve the situation.

Table 1 provides an example of the distinction made between ‘area of practice’, ‘situation of interest’ and a ‘system of interest’.

| Term | Example | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Area of practice | hospital management | generalised role or area of responsibility, identifying generic types of concerns |

| Situation of interest | current concerns about funding at Mouseville hospital | more specific area of concern, situation or event that is perceived by someone as calling for some kind of intervention |

| System of interest | system to manage resources at Mouseville hospital | particular arrangement of activities associated with a situation designed to achieve a particular purpose |

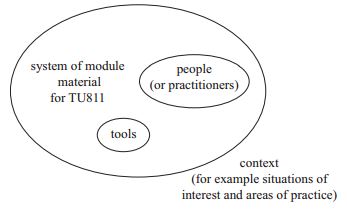

The relationship between three factors associated with strategic intervention context, people, and tools − can be represented by a systems map that identifies boundaries between the three factors.

The diagram below illustrates the map in relation to the way in which The Open University course TU811 ‘Thinking Strategically: systems tools for managing change’ was conceived. The course aimed towards taking participants on a Tools stream of learning based on gaining practical experience in using and adapting tools from the five systems approaches. A parallel People stream of learning was created enabling critical reflection in the use of the ‘tools’.

Three important boundaries are located in the systems map:

The major boundary is between the system of interest and everything else – everything else being the context. It is partly a marker to indicate the issue currently of interest. It is also a reminder that beyond it is a world of all manner of unpredictable influences, and the world is also likely to be affected by whatever the system of interest does. This outer area is often called the system's environment. Among many other factors the environment for this module consists of the area of practice that you choose to work with.

Another boundary marks out the practitioners. I've placed it inside the system of interest. Of course any real human practitioner is part of a great many systems of interest, so I could have put the practitioner blob half in and half out of the system of interest, to indicate this other life out in the environment.

The third boundary marks out the tools the practitioners use. Again, I could have put it half in and half out, because there are all manner of conceptual tools available, in addition to those associated with the five systems approaches.

The distinction between the two latter subsystems is reflected in the separation between the Tools and People streams.

Activity 6 Context Matters

Read the beginning of section 1.2 and continuing into 1.2.1 in Introducing Systems Approaches. Then read the final section of 7.3 ‘Context Always Matters’ from the Systems Approaches Epilogue. The first reading provides a description of three media stories of 2009 – the Hillsborough football stadium tragedy in the UK, sea piracy in Somalia, and protection of Orangutans in Indonesia; all three of which encapsulate ‘messy’ situations. The second reading provides a brief sketch of possible uses of tools from each of the five systems approaches in dealing with each of the three situations. The reading describes the three stories in terms of:

- i.key inter-related variables

- ii.different perspectives

- iii.boundary conflicts.

In reflecting on your own area of practice (e.g. your own professional practice or an area of practice that you may have an interest, such as health, business management, education, sustainable development, family welfare etc.) make some brief notes on:

- a.some key interrelationships between variables

- b.some contrasting perspectives

- c.some possible tensions among practitioners regarding levels of uncertainty or conflict in perspectives.

From your brief introduction to systems thinking in practice in this course, describe how systems approaches might offer support towards designing systemic strategies to improve the situations that you have noted.

Discussion

In this introductory course you will not be expected to have gained know-how in the application of any of the five systems approaches introduced. But generically, you hopefully will have gained some appreciation of the potential in your chosen area of practice for systems tools to provide:

- i.a more holistic picture of the variables and their inter-relationships

- ii.a means of depicting perspectives as systems of interest using different modelling techniques (SD, VSM, SSM, cognitive mapping, CSH reference systems…)

- iii.a means of resolving issues of conflict by making boundaries of what’s in and what’s out explicit – countering claims of holism, and making boundaries of perspectives (viewpoints) explicit – countering claims of pluralism.

The context of using systems thinking in practice involves not just the variables (complicatedness), perspectives (complexity), and boundaries (conflicts) in the area of practice, but also your own experiences and enthusiasms drawn from whatever background or tradition of practice that you may come from. Systems tools – whether from the five systems approaches or other approaches – are not necessarily introduced as yet another alternative set of tools, but rather a complementary set of ideas that may help enhance your existing practice.

4 Summary

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That's how the light gets in

The Leonard Cohen verse was used at the beginning of the first part of this course. I thought of the bells that still can ring as tools collectively constituting the five systems approaches. To some extent they are disembodied and externalised. You can learn the techniques of ‘bell ringing’ through practicing with the use of systems tools in your own area of practice, and in so doing make use of them as a practitioner.

But behind the techniques in any situation there are the bell ringers. Not only do they have the experiences that they bring to bear on the skill of bell-ringing (tool use), but also the uniquely human qualities that determine how and why they do it as they do, and that allow them to enjoy and appreciate it. Such practitioners are the users of the tools – including myself, you and others studying this course. Practitioners are what the People stream is about, as it takes a look at how people think, how their thinking differs, and how they wield the tools.

Thinking strategically in practice requires prime attention to the present context and the foreseeable future. I have emphasised the importance of relationship between:

- situations of interest (in areas of practice) as raw material for using tools

- practitioner or tool user attempting to improve the situation

- actual tools used.

The term ‘tools’ is used in a generic sense to incorporate the systems thinking and systems practice ideas embodied in the systems approaches introduced in this course. Other ideas from outside the systems approaches can provide an additional source for reflecting upon the use of systems tools. Systems thinking and systems practice provide conceptual tools for dealing with three features of complex situations of change encountered when thinking strategically:

- making sense of countless interrelated and often interdependent variables

- engaging with multiple contrasting and often conflicting perspectives

- dealing effectively and constructively with boundary tensions arising from inevitable uncertainty about interrelationships and interdependencies and conflicts between contrasting perspectives.

The five approaches were chosen because of their respective pedigrees in supporting strategic decision making in different and changing contexts. Each approach embodies all three imperatives of systems thinking and systems practice summarised above. But each approach also has an historic slant towards one imperative. System dynamics and the viable system model are particularly significant in dealing with interrelationships among variables. Strategic options development and analysis, and soft systems methodology are particularly significant approaches in dealing with multiple perspectives. Critical systems heuristics is particularly significant in dealing with boundary tensions.

The important point to take forward if practising any of the five systems approaches is to continually reflect on how the approaches and their respective tools can enrich your existing capacities for thinking strategically in dealing with present messy situations in order to improve them for the future.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Martin Reynolds.

This free course is adapted from a former Open University course Thinking strategically: systems tools for managing change (TU811).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Text

Activities 1, 7: Chapter 1 from M. Reynolds and S. Holwell (eds.), Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide, DOI 10.1007/978-1-84882-809-4_1, © The Open University 2010. Published in Association with Springer-Verlag London Limited.

Activities 2, 4,7: from Chapter 7: M. Reynolds and S. Holwell (eds.), Systems Approaches to Managing Change:A Practical Guide, DOI 10.1007/978-1-84882-809-4_7, © The Open University 2010. Published in Association with Springer-Verlag London Limited.

Box 1: extract from: Box 4: Cabinet Office (2004) Systems Thinking in Practice, [online], Prime Minister's Strategy Unit, http://interactive.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/strategy/survivalguide/skills/systems.htm49 © Crown Copyright 2004.

4. Extract from: Cohen, L. (1993) Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs, New York, Pantheon Books. © Leonard Cohen (1993).

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2016 The Open University