3 Chinese economic reforms and energy security

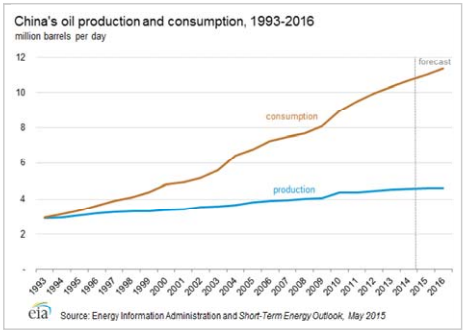

Since the ‘open door’ era started in 1978, the Chinese economy has experienced an unprecedentedly rapid growth, lasting for nearly 40 years. This growth enabled China to become the world’s second largest economy in 2010, after the United States (Leung, 2011). As mentioned in the introduction, accompanying this growth was a rapid rise in China’s energy consumption. According to the China National Bureau of Statistic (NBS) and the BP Statistical Review of World Energy (BP Energy), between 1978 and 2017 China’s energy demands increased nearly 5.5 times, from 571.44mts of oil equivalent (Mtoe) to 3.13 billion Mtoe. In 1993, China turned into a net oil importer from a net exporter, and its oil consumption grew more than five times from 2.41 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 1991 to 12.8 mb/d in 2017 (as shown in Figure 8). In 2008, China surpassed Japan to be the world’s second largest crude importer, and in 2013, it overtook the United States to be the top oil importer on the planet. By 2017, China had to import 422 mts of crude oil to meet its demands, accounting for 69 per cent of the country’s oil consumption (NBS Yearbook, 2007; BP Energy, 2002 and 2018).

In the mid-1990s, when the shortage of domestic oil supply became obvious and irreversible, the Chinese leadership was initially tempted to insist on the Maoist principle of ‘self-reliance’, and attempted to exploit domestic sources. It was only after the promises of the oil field in Xinjiang Province and offshore petroleum exploration in the East and South China Seas failed to materialise, that the Chinese leadership was forced to accept that China would have to rely more on oil imports and to do so for the long-term.

From the late 1990s, China’s top leadership started to consider ‘walking on two legs’ – a policy of utilising both domestic and international resources. The then Secretary-General of the Chinese Communist Party – Jiang Zemin – argued in January 1997 that ‘we will still focus on domestic resources in developing our petroleum industry, … but also need to actively participate and utilize international resources, i.e. to walk on two legs’ (Wu, 2018). Under the new policy guidance, China’s oil imports have shown a constant increase and Chinese NOCs have also gone global, with Africa as one of the significant locations to help it achieve oil security.

These large oil companies had not always been relatively autonomous from the Chinese Communist Party, but evolved out of various reforms and restructurings. The Chinese economic system during Mao Zedong’s era (1949–1976) followed the Soviet model of a planned economy, which allowed little role for the market. Major industries did not operate as commercial entities but were instead directly subordinated to government ministries. Only after a series of government reforms, begun in 1982, aiming to separate the government from the industries were the industrial functions removed from the ministries. Three major state-owned oil companies – the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), the China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) – came into being during this process (Liao, 2015).

Entering the new century, the three Chinese NOCs were listed on the international stock markets, which theoretically would allow them to better integrate with the international system in operation and in efficiency. In practice, the NOCs were allowed to enjoy a prescribed regional monopoly in the Chinese oil market and in return they were expected to share responsibility for helping the Chinese leadership ensure a stable oil supply (Shi, 2006). The mechanism for Beijing to influence the companies’ performance was through the control over the appointment and dismissal of the NOCs’ leadership, which is assessed ‘not only on how well they run their companies, but also on how well they serve the CCP’s [Chinese Communist Party] interests’ (Downs, 2006, p. 23). If they can demonstrate success in both areas the NOCs’ executives have a chance to be promoted to higher positions.

The new millennium ushered in further reforms and new policy initiatives aimed at boosting the international competitiveness of China’s large state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which included the NOCs.