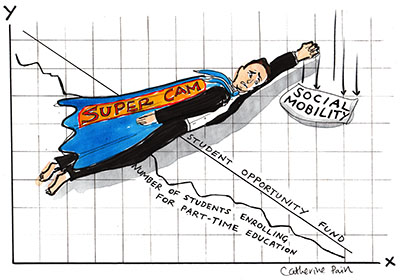

The prime minister has pledged to double the number of students from disadvantaged backgrounds entering higher education by 2020. David Cameron has signalled an all-out attack on poverty and has thrown down the gauntlet to universities to deliver on social justice.

The prime minister has pledged to double the number of students from disadvantaged backgrounds entering higher education by 2020. David Cameron has signalled an all-out attack on poverty and has thrown down the gauntlet to universities to deliver on social justice.

He will be aware that many universities already have a proud history of widening participation to students from groups traditionally under-represented in higher education. Disadvantaged youngsters were 70% more likely to enter higher education in 2014 than they were in 2004.

The universities which have had most impact in widening participation include Bolton, Edge Hill, Greenwich, London Metropolitan, London South Bank, Sunderland, Teeside and Wolverhampton. Until 1992, these were all former polytechnics, and are now known as “new” or post-92 universities, which tend to have missions to support students from all backgrounds to succeed.

I fear, in challenging higher education to address social mobility, the prime minister may be thinking only about more of those ubiquitous 18-year-old school leavers aiming at full-time undergraduate study. But given the gradual demographic fall in the number of 18-year-olds since 2011, there will not be enough of these potential students to have a significant impact on aspirations for a more equal society – to say nothing of addressing Britain’s skills shortages.

My own research suggests the key disadvantaged group on which universities could have a quicker, and more transformative impact, are mature learners who are limited by personal circumstances to part-time study.

These part-time students include everybody from adults who missed out at 18 and aspire for a second chance while working and learners with low or alternative entry qualifications, to poorer learners in low-status jobs – often women who are seeking a transformative life chance to benefit their families.

Their needs cannot be met by the inflexibilities inherent in mainstream full-time higher education. If universities were further given incentives to offer more attractive, flexible and affordable part-time courses, the prime minister’s aspirations for a more equal society could be met through higher education.

Yet the most recent data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency demonstrates that the number of students enrolling for UK part-time higher education decreased by 6% between the 2013-14 and 2014-15 academic years.

The proportion of undergraduates studying part-time continues to fall, and is now down to 25% of the total. This dramatic decline is acutely relevant to Cameron’s pledge: part-timers are the most vulnerable in the sector.

Securing student opportunity

The crucial source of funding, which enables many in the higher education sector to support activities to help disadvantaged students to succeed, is the Student Opportunity Fund. Money from this is distributed to universities in England who charge fees between £6,000 to a maximum £9,000 for full-time students, and £4,500 to £6,750 for part-time students.

The fund is used to meet the needs of a wide range of students, recognising that learners from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to complete their studies and need customised support.

Learners from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to achieve a “good” pass (a first or upper second class honours degree). For example, last year students from neighbourhoods with the lowest higher education participation rate were 11% less likely to achieve a good degree than those from areas with the highest participation. Mature students are also 11% less likely than younger students to gain a good degree, and part-time students are 18% less likely than full-timers.

All universities offering part-time learning depend on the Student Opportunity Fund. At my own institution, The Open University – where 18% of all new student registrations are from a low socio-economic background – dedicated learner support and inclusive materials are embedded in the student experience. With 16% of our undergraduates declaring a disability, the university also targets them with pre-entry advice and technologies, including specialist equipment to support study independence. This ranges from voice recognition software for physically disabled learners to the conversion of print materials into an electronic form, read out in a synthetic voice, for blind students.

Demands for such support has increased in recent years, as the number of disabled students across the sector has risen. We are also experiencing far more students presenting mental health issues. My research suggested that characteristics such as disability may overlap with low socio-economic status, as people can be excluded from employment opportunities and reliant on benefits. As a result, students enrol in university with a potentially toxic set of barriers to learning.

Uncertain future

Universities are bracing themselves while the Department of Business and Skills (BiS) considers options for higher education funding following the government’s spending review. The annual higher education grant letter from the Higher Education Funding Council for England, which sets out how much state funding universities receive, will have to be sent by May at the latest.

The sector fears that the funding universities receive to attract disadvantaged learners will be restructured, reducing the amount spent on measures to widen participation – including the Student Opportunity Fund – by 50% over the next five years.

The government could address these fears, by safeguarding rather than cutting the fund. There is a pressing need for it. Protecting it will enable universities to support the prime minister’s pledges for a more just society by supporting those universities which enable the most disadvantaged in society to achieve the goals of greater chances in life.

This blog post is part of Society Matters. The blog seeks to inform, stimulate and challenge our understanding of this changing world and of our humbling role within it.

Want to know more about studying social sciences at The Open University? Visit the Social Sciences faculty site.

Please note: The opinions expressed in Society Matters posts are those of the individual authors, and do not represent the views of The Open University.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews