Sometimes events unfold in a way that seems almost too good to be true. When PhD student Ross Findlay discovered that the Winchcombe meteorite fireball shot past his childhood home, a little bit due west of Tewkesbury, he was excited about the possibility of small fragments being found in the farmland he grew up in. Alas, the rocky fragments of meteorite made landfall just a little further east, but this didn’t mark the end of Ross’s involvement in the recovery and analysis of the first UK meteorite in 30 years.

Ross is undertaking a PhD studying meteorite samples, many of which are recently recovered falls just like the Winchcombe meteorite, but also a few that have been collected in cold deserts like Antarctica. However, he has never before worked on a meteorite that was collected less than 100 miles from his laboratory at The Open University in Milton Keynes. The reason being is that meteorite falls in the UK are not very commonplace. Ross’s work had him well-placed, both geographically and academically to help classify the newly-recovered Winchcombe meteorite, since he was in the lab the same week it was recovered, working on very similar rocks.

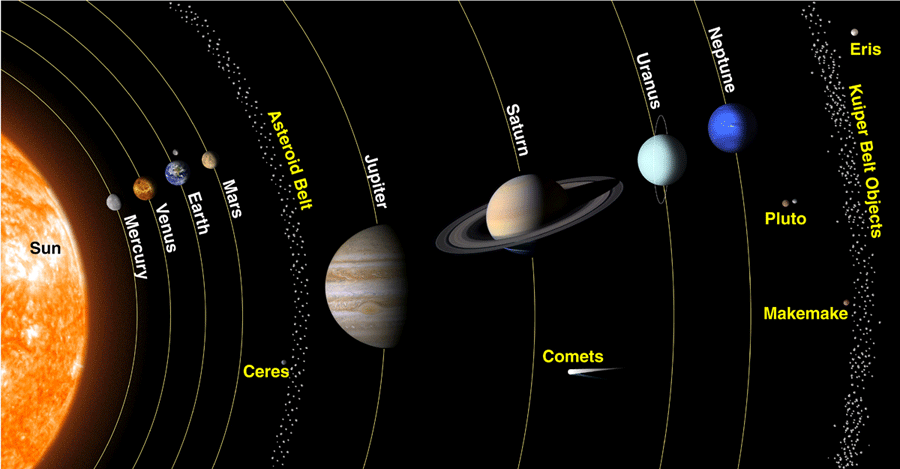

The Winchcombe meteorite.

The Winchcombe meteorite.

Ross explained: “My work centres around understanding how water evolved in the early Solar System, including how our own planet came to possess such vast oceans. To do this I look at water rich meteorites called CM chondrites, which probably come from very old asteroids formed early in Solar System history, and may have even brought water to Earth when the Solar System was in its infancy. I use the element oxygen to trace what water was up to all those years ago and how it may have interacted with the early rocks. That’s not the only use for oxygen though, as it has another neat little trick up its sleeve! All meteorite “families” have a unique oxygen isotope signature, a bit like a fingerprint, allowing us to get a really good idea of what type of meteorite it is and where it belongs in the meteorite family tree.”

Dr Richard Greenwood, who works alongside Ross supervising his PhD work, was involved in the identification and recovery of the meteorite in the village of Winchcombe. As soon as he saw the almost jet black, extremely fragile rock for the first time he knew it was very primitive, which suggested it could be a water-rich carbonaceous meteorite, like the CM meteorites Ross studies.

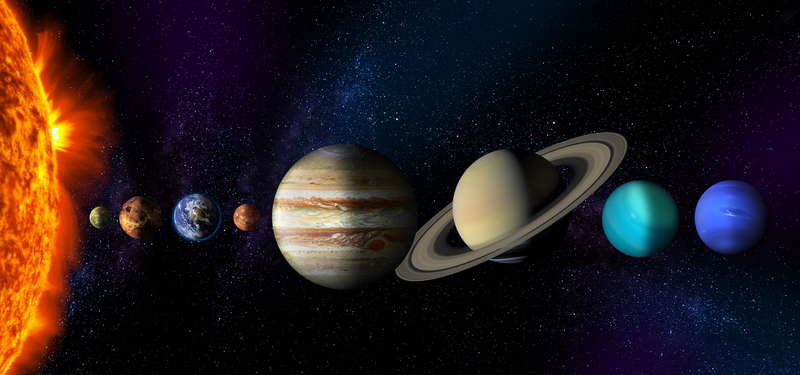

Ross went on to explain: “Excitingly, the fact that the meteorite was photographed by an extensive camera network allowed some scientists to reconstruct the orbital trajectory of the rock, indicating that it may have come from the outer asteroid belt, a region where water would have existed in the early Solar System.”

The inner and outer planets of our Solar System.

The inner and outer planets of our Solar System.

The Open University is equipped with an excellent oxygen isotope facility, and much experience in the analysis of extra-terrestrial samples. Consequently, a mere four days after the Winchcombe meteorite fell to the ground, Ross was looking at the numbers churned out by the mass spectrometer in one of the fastest “outer space to mass spectrometer” analyses ever made! The preliminary oxygen isotope data certainly support a carbonaceous chondrite classification. At the time of writing, there was still much to learn about the Winchcombe meteorite, with the bulk of the rock carefully curated at The Natural History Museum in London ready for further analyses.

For Ross, it was certainly a whirlwind and surreal couple of weeks. Out of all the groups of meteorites, of which there are over 40 in our collections on Earth, the Winchcombe rock was almost identical to the type of meteorites Ross studies, and of which there are relatively few samples available for scientists to study on Earth.

“To put the cherry on the cake, it landed in my home county of Gloucestershire, and was then tracked down by my supervisor! What a lucky person I am, indeed!”.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews