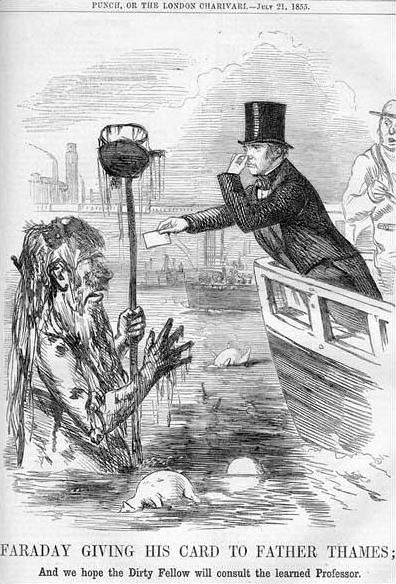

Michael Faraday hands Father Thames a card during one of the 'great stinks' - a Punch cartoon from 1855

Poor Old Father Thames, once the object of poetic admiration, and much bepraised in mellifluous strains, has now to endure the most vindictively abusive epithets ever lavished upon unfortunate river god. And why this cruel reverse?

Michael Faraday hands Father Thames a card during one of the 'great stinks' - a Punch cartoon from 1855

Poor Old Father Thames, once the object of poetic admiration, and much bepraised in mellifluous strains, has now to endure the most vindictively abusive epithets ever lavished upon unfortunate river god. And why this cruel reverse?

Not from any faulty on his part, but simply because the metropolis was frightened some years ago out of its propriety by some well-meaning but short-sighted sanitary doctors. The cholera swept through the town with destructive violence, and people at last believed that it and typhus - its kindred scourge - drew their strength from the ill-drained houses and reeking cesspits. Like all converts, their zeal was greater than their discretion.

They listened to the solemn denunciations of cesspools which issued from Whitehall, and the cesspools were filled up. But the filth which used to find its way to the cesspool had to be carried somewhere, and the Thames was at once selected for its receptacle.

So, as cesspools have disappeared, and houses have been better drained, the whilome [formerly] silvery Thames has become filthier and filthier, until at last it threatens to produce still deadlier maladies than cesspools in every street would have done.

In fact, in our reforming zeal, we have merely changed a hundred thousand small cesspools for one moster one. We undertook only a part of the necessary work, and that not the most important part.

When the old Board of Health resolved that every house should be drained, they ought alos to have found a sufficient means of carrying off the filth so removed from houses; but the task was too much for them, and, carrying off the honours of originating sanitary reform, they left the heaviest part of the work to parochial delegates.

So our streets were well-drained, the filth is entirely carried off; but all goes to a sewer lying in the heart of the town, perfectly open - the great silent highway which bathes the terrace upon which stands the Legislative Palace, and so peculiarly fashioned that it retains the filth it receives for days. Fancy an open sewer stirred up twice a day by some powerful mechanism, and we have the Thames as altered by well-intentioned but blind sanitary zeal.

And for three years more, at the least, we must make up our minds to bear the nuisance unless, indeed, science can in the meantime discover any palliative. At the end of that time, part, if not all, of the great main drainage system, which the Thames' stench of last summer forced the dilatory authorities to adopt, will be in action.

The price London will have to pay for the relief is heavy; but, great as may be the burden on the ratepayers, there are few, we believe, who would object to meet it at once if the work could be at once accomplished. Of that, however, there is no chance.

Gigantic operations of this kind require some years for their completion, and no one will be so unreasonable as to expect them done off-hand.

It may be questioned, however, whether the Board of Works has displayed all the despatch which might fairly be required of it. The main drainage system adopted consists, as our readers are probably aware, of six immense tunnels, three on each side of the river, and intended to carry as far as Barking the whole of London sewage.

At Barking the sewage enters a reservoir, where it is to be deodorized; and thence, at high water, passed into the middle of the river, it being anticipated that the whole mass will be at once carried off by the ebbing tide.

Of these tunnels, however, only one - the high-level sewer on the north side of the river - has been commenced. We are not aware that the difficulties in the construction of this particular sewer are so great that it required a much longer time for its completion than the others, and we cannot therefore understand why they should not be forthwith commenced. There is no lack of contractors able and willing to execute such works, nor can there rightly be any want of money, inasmuch as the Bank of England has engaged to advance all the sums necessary for carrying out the scheme.

It only rests, therefore, with the Metropolitan Board to invite tenders for the different works, and it is to be hoped that no further delay will be allowed to take place.

Looking at the question merely from a pecuniary point of view, it is most desirable that the operations should be hastened, as the Thames, under present circumstances, is necessarily a source of great and continually increasing expense.

Cost, however, what it may, the stench of the great river must, if possible, be kept under. The destruction caused by a pestilence is not to be reckoned by hundreds of thousands or even millions of pounds; and even if we escape some fearful outbreak of disease this summer, the public sustain an amount of inconvenience and injury from the state of the river, which would be economically got rid of by a large pecuniary outlay.

As it is, it is cruel to keep Members of Parliament at their posts, although the business they have to do is of the most pressing character, and when the election committees sit, and the rooms and corridors are crowded with the witnesses and parties interested, the state of the unlucky Members engaged in the always unpleasant task will be most pitiable. They will not be able to open the doors on account of the noise, and they cannot open the windows on account of the stench.

But Members of Parliament are much better off than many other classes. They can get away for part of the day, and breathe fresh air. The unfortunate people who live close to the banks of the stream must, most of them, stay continually within its baleful influence.

Cholera may, happily, not break out; but in any case the fetod odours the river regularly omits must produce much sickness and suffering in those exposed to them.

Nor is it an unimportant matter in a metropolis like this, in which intercommunication is comparatively so difficulty, that one of the best, cheapest, and most frequented highways is practically shut up.

Whatever, therefore, the cost, the Board of Works must go on with its disinfecting operations. It is of no use promising us health and comfort five years hence, if we are all to be poisoned this summer or the next.

Our appreciation of the new main drainage system will not be the less, even if by clever doctoring the Thames should be kept tolerably inodorous for the next two or three summers.

The Board of Works has a great many minor functions, but it has two great duties which, at any sacrifice of others, it must fulfil: the one, to press on with the utmost energy the main drainage of London; and the other, to keep the Thames in the meantime from destroying the dwellers on its banks.

- The Morning Chronicle, 20-07-1859

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT? If the Chronicle was hoping to only have to endure a couple of stinky summers, it was going to be disappointed - the sewer work would drag on until 1865, and the Victoria Embankment - the final part of the massive project, the Victoria Embankment, wasn't officially opened until July 1870. However, the works themselves were a great success; the cement built sewer system lasted well into the 20th Century - and had London's population not expanded so rapidly, the tunnels would probably still be happily carting sewage away from the City now. However, with many more people, and much more built-up area, London sewers have been crying out for a 21st Century upgrade. That work is now underway.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews