3.1 The acquisitive model of learning

The three models are introduced in turn, and each is followed by an activity that invites you to apply the model to your studies.

This model of learning starts from a focus on the observable behaviour of the learner and on the idea that this can be changed by feedback from the learning environment. It is associated with the idea that learning has to do with reproducing some desirable behaviours or measurable outcomes.

The learning process is seen as a process of accretion. Learners add to their store of knowledge those items that are required for them to achieve their current goal. Teaching, therefore, starts with the analysis of what is to be learned, so that it can be broken down into component parts which can be taught stage by stage. Each part is taught in a predetermined order and tested before the next part is learned so that the desired behaviour builds up incrementally.

It is essential to this process that learners have feedback regularly on how effectively they are achieving the desired learning outcome at each stage. If the learning is part of an education or training programme, the feedback is likely to result from some form of assessed performance and to include the response of a tutor. Feedback gives the learner information about how close they are to achieving the required outcomes so that they can modify and develop what they do in the required direction.

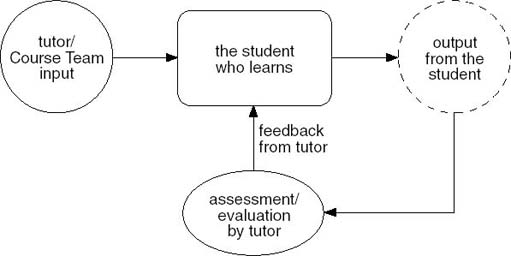

This approach to how learning happens has some similarities to an input/output model, with a feedback loop for correction of what has been recalled (see Figure 1). It also has some similarities with everyday thinking about learning, in that people commonly think of learning as knowing more: knowledge is a fixed object which one has more or less of, and learning is the process of acquiring more of it. The test of having learned is evidence that one can reproduce a near-exact replica of the knowledge or skill that was the objective of the exercise.

This approach to learning emphasises the desired outputs of the process but says little or nothing about what the learner should be doing or thinking while learning. The person doing the learning is simply a 'black box', taking in the information and generating the output, whatever that is.

The limitations of this model have frequently been recognised. Learning is not a passive process of absorption of an input, unmodified. It is an active process where the same input does not reliably produce the desired output. The same input and feedback will not produce good results with all earners, or even with the same learner all of the time. What goes on when we learn, and the influences that affect that process, have been left out in this model.

Also, for many things that we have to learn, successful learning cannot be adequately demonstrated in some form of behaviour. Much of what we must learn, for example, comprises not of details to be remembered, but ideas to be understood, and techniques for analysing and evaluating information. We also have to learn about attitudes, which may require us to change our perceptions, or to understand feelings different from our own. A simple input/output model will not take us very far with this kind of learning.

Nonetheless, in spite of its flaws, the acquisitive model is often implicit in the way we teach and learn. It has been used to produce effective learning opportunities for some purposes, and it can be modified in a number of ways to take into account the active role of the learner during learning. It can be modified, for example, to help the learner make a more coherent whole of topics learned in small, isolated chunks. In addition, some of the core ideas about breaking down what is to be learned into a paced programme of study, and providing regular feedback, have proved important for effective learning in a wide range of areas.

Activity 4 suggests that information which we simply need to know or to apply in problem-solving exercises might be learned by applying a modified acquisitive approach. Try out the activity to see whether this might suit the way you wish to study some parts of this course.

Activity 4

Memorising

There are units on OpenLearn that explain terms or concepts which may well be new to you and which would be useful for further study. Consider, for example, T551 Systems Thinking and Practice [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . The whole terminology used there of system, boundary and environment along with distinctions between systemic and systematic, reductionism and holism, interconnectedness and feedback is being used in a particular way, even if the words themselves are familiar. If this is new to you, you would need to find a way of familiarising yourself with some key terms and information. One way to do this is to select some key items from learning material and to re-organise them in two different ways:

-

in the form of a spray diagram

-

in the form of a set of questions on which you can test yourself or get someone else to test you.

Most of the hard work of sorting out what a system is and how it can be used as an aid to thinking has been done already, but reading through the learning material is not usually enough to enable us to remember the key points. One way of helping yourself to do this is to create a situation which gives you feedback on gaps in your knowledge.

Take the second suggestion listed above, which is to make up a set of questions from the material. Skim over the T551 course in question to get an idea of the course contents. If you studied this course, the list of questions might look something like this:

-

Name the three ways of thinking described.

-

How does positive feedback differ from negative feedback?

-

What is the full definition of a system of interest?

-

How can you distinguish between hard and soft complexity?

-

In what ways are levels and boundaries related?

When you've done some studying, you should try testing yourself to check out your memory of what could be considered basic information within the course. Better still, ask someone else to do so after a day or two, so that your immediate memory of the questions has faded.

If you do need to check up the answers, as you do so, you could draw a diagram or make further notes in your learning file to help you remember the key points.

You can use a similar approach to help you remember key points from the study of very large amounts of text. This is what we do when we reduce our notes to headings and try to memorise these in preparation for an exam. The headings are there to provide a reminder of all the details which we can then unpack in order to make arguments appropriate to the questions we have to answer.

Re-organising information, or reducing detail to summary lists and diagrams which we can reconstruct and check out through self testing with feedback, is useful for building up recognition and memory. It helps to create mental structures which support our need to review what we know and to use it flexibly, according to the immediate requirement. This kind of activity has been devalued because of its link with pre-examination cramming. But it can have a useful role for remembering both detailed information and summaries of key points. That is, it is a study skill to use at regular intervals.