3.3 Cognitive models

Cognitive theories consider the manner in which people think about and process personal information, by focusing on core beliefs (formed during early life experiences; unconscious beliefs about self, others and the world), underlying assumptions (spontaneous thoughts or prompts arising from core beliefs) and systematic negative bias in thinking. An assumption of this approach is that altered thinking processes precede the onset of depressed mood. Aaron Beck (Beck, 1967a and 1967b) proposed three mechanisms underlying the ‘negative appraisal’ of events in depression: the cognitive triad (negative automatic thinking), negative self schemas and errors in logic (altered processing of information).

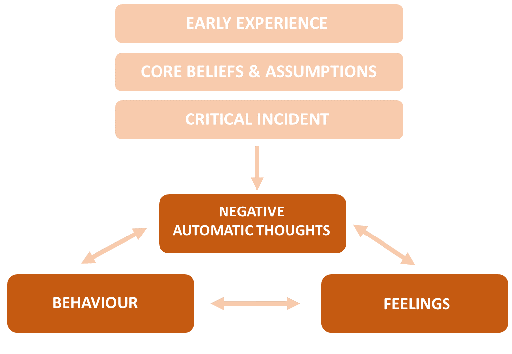

Beck’s (1967) cognitive triad model of depression identifies three common forms of negative (helpless and/or critical) self-referent thinking which occur spontaneously (‘automatically’) in individuals with depression: negative thoughts about the self, the world and the future. The three core beliefs (which encompass feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness) interact and interfere with cognitive processing, leading to impairments in perception, memory, problem solving and reinforce an ‘obsession’ with negative thinking. According to the model (see Figure 1), negative beliefs and expectations may be acquired in childhood as a consequence of a traumatic event(s) such as death of a parent or sibling, parental rejection, criticism or overprotective parenting, neglect or abuse, bullying or exclusion from a peer group. These can predispose the individual to depression. A subsequent stressful life event or a critical incident in later life can act to trigger the schema, and activate systematic negative (biased) thinking whereby the individual tends to focus selectively on certain aspects of a situation or event, while ignoring other relevant information. Negative thoughts will often persist even in the face of contrary evidence. These ‘cognitive distortions’ (i.e. systematic negative biases in thinking), can be self-defeating and a significant source of anxiety or depression for the individual (see Box 9).

Depression typically involves a negative view of oneself, the world and the future.

Box 9 Cognitive distortions (systematic negative biases in thinking) that can contribute to depression (adapted from Beck, 1967a; Burns, 1999 and 2000)

| Dichotomous (‘all or nothing’) thinking | Looking at things in absolute (‘black or white’) categories with no middle ground, e.g. ‘If I fall short of perfection, I’m a total failure’. |

| Overgeneralisation | Generalising from a single negative experience and viewing this as a never-ending pattern of defeat, e.g. ‘I didn’t get hired for the job, I’ll never get any job’. |

| Mental filtering | Dwelling on the negatives, filtering out the positives, e.g. focusing on one or two things that went wrong, rather than all of the things that went right. |

| Disqualifying or discounting or diminishing the positives | Rejecting positive experiences, qualities or accomplishments, insisting that they ‘don’t count’,e.g. ‘I did well on the presentation, but that was just pure luck’. |

| Jumping to conclusions | Drawing negative conclusions even though there is insufficient evidence or not warranted by facts, such asassuming that people are reacting negatively to you when there’s no definitive evidence (‘mind reading’), e.g. ‘I can tell she secretly hates me’; you arbitrarily predict that things will turn out badly (‘fortune telling’), e.g. ‘I just know something terrible is going to happen’. |

| Magnifying or minimising | Blowing things out of proportion or shrinking their importance. |

| Emotional reasoning | Reasoning from one’s subjective feelings. Believing that the way you feel reflects reality. e.g. ‘I feel like an idiot, so I really must be one’, or ‘I feel hopeless; this means I’ll never get better’. |

| Catastrophising | Assuming extreme and horrible consequences of events. Expecting the worse-case scenario,e.g. ‘The pilot said we’re in for some turbulence; the plane’s going to crash!’ |

| ‘Should’ statements | Holding oneself and others to strict rules of what should and shouldn’t (‘ought’, ‘must’ or ‘have to’) be done; criticising or being hard on yourself for breaking any rules. Self-directed ‘should’ statements lead to feelings of guilt and inferiority’; directing ‘should’ statements at others can lead to feelings of bitterness, anger and frustration. Hidden ‘shoulds’ are rules that are implied by your negative thoughts. |

| Labelling | Labelling yourself based on mistakes and perceived shortcomings, e.g. instead of saying ‘I made a mistake’ you tell yourself ‘I’m a failure, an idiot, a loser’. |

| Personalisation and blame | Assuming responsibility for things that are beyond one’s control, e.g. ‘It’s my fault that my friend had the accident; I should have warned her not to drive in the rain’. Finding fault instead of solving the problem, e.g. blaming yourself for something that you weren’t entirely responsible for (self-blame) or blaming others and overlooking ways in which you may have contributed, or denying your role in the problem (other-blame). |

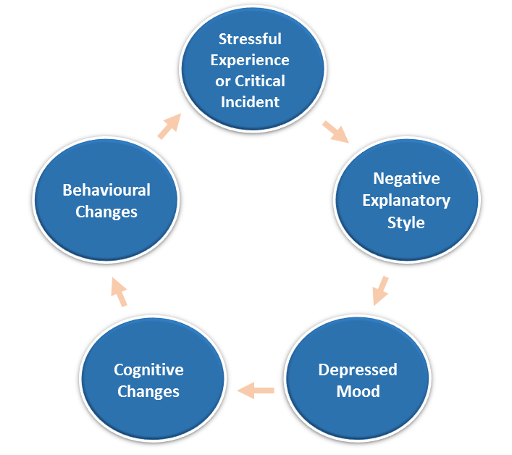

If negative interpretations of situations are not challenged, the patterns of thoughts, feelings and behaviours become increasingly repetitive and intrusive and can be repeated as part of a debilitating cycle (see Figure 2). However, while correlation between cognitive style and development of depression is suggested by this model, it is unclear whether maladaptive cognitive processes and negative thinking such as those described above are a consequence rather than a cause for depression (i.e. they may accompany and persist in depression, but do not predispose or predict the onset of depression).

Seligman’s ‘learned helplessness’ theory, another psychological explanation for depression, considers depression to arise as a consequence of a person’s futile attempts to escape ‘negative’ situations (Seligman, 1973-1975). Seligman based this theory on experiments conducted in dogs. When dogs were subjected to mild electric shock delivered through the floor of their housing, but had access to a partitioned area, escape was possible by crossing over to the ‘shock-free’ area. When restrained, however, and escape was no longer possible, they eventually stopped attempting to escape. When subjected to repeated ‘inescapable’ shocks in this way, they not only failed to escape even when it was later possible to do so, but also exhibited some symptoms associated with depression in humans (e.g. passive, lethargic behaviour in the face of stress and loss of appetite). While such experiments do raise ethical considerations, at the time they did offer an explanation for depression in humans as a condition whereby an individual would learn that they are helpless as a consequence of having lack of control over what happens to them.

Abramson, Seligman and Teasdale (1978) reformulated this hypothesis to include a cognitive process whereby an individual could ‘attribute’ or explain the ‘cause’ for an event. The attribution model is based on three ‘causal’ dimensions: (i) whether the cause is internal or external to the individual, (ii) whether the cause is stable and permanent, or transient in nature, and (iii) whether it is global (affecting all areas of life) or specific. Abramson et al. argued that people who attributed failure to internal, stable and global causes were more likely to become depressed, as they would come to the conclusion that they were unable to influence or control the situation for the better. Attributions to internal factors are tied to feelings of worthlessness, whereas attributions to stable and global factors are linked to feelings of hopelessness and despair.

For example, if a person loses their job, and they attribute this to some failing on their part (internal dimension), and they also see things as not working out for them in other areas (global dimension), and view this as a long-term pattern of failure and disappointment in the future (stable dimension), then they are likely to become depressed. On the other hand, if they view the loss of a job as being due to circumstances beyond their control (external dimension), as an event that was unique to the situation (specific dimension), and as something that did not represent any pattern in the future (unstable dimension) they would be likely to handle this well emotionally, according to this model.

Abramson, Metalsky and Alloy (1989) further revised the model, integrating Beck’s (1976) theory with a reformulated learned helplessness model to derive the ‘hopelessness theory of depression’. In keeping with the diathesis-stress model of depression, the theory considers depression to arise when people with a negative attributional style interpret a stressful life event in negative terms. These interpretations give rise to hopelessness, seen as an immediate cause of a particular ‘subtype’ of depression. Once again, however, whether ‘helplessness’ or ‘hopelessness’ are symptoms (or manifestations) rather than a cause of depression, remain unclear.