The recent AI Safety Summit and press coverage suggest we need to think carefully about these new urban technologies. On one hand, the benefits of these new automated technologies such as driverless cars and delivery robots may be significant. For example, these new technologies may improve accessibility to essential food supplies for older people and may be particularly useful for such purposes during major disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme weather events such as blizzards or heatwaves.

Figure 1: Delivery robots received particular attention in 2018 during the blizzards associated with Storm Emma, and later during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Delivery robots received particular attention in 2018 during the blizzards associated with Storm Emma, and later during the COVID-19 pandemic.

More generally, automated technologies may reduce our dependency on the car as a means of travel and ultimately make cities less reliant on automobility. On the other hand, automated technologies may have unintended consequences which are difficult to tackle.

For example, robots are widely used in factories and to make them work effectively in cities, there is growing concern that the urban fabric may need to become a little like factories.

Figure 2: Autonomous shuttle test. Although a driver had to be present during the demonstration for purposes of safety, this was a hands-free role as AI was in control of the shuttle.

Figure 2: Autonomous shuttle test. Although a driver had to be present during the demonstration for purposes of safety, this was a hands-free role as AI was in control of the shuttle.

Also, if AI is embedded in so-called ‘city brains’ which manage key aspects of cities such as traffic flows, AI might make decisions humans don’t agree with but are powerless to change.

Whether these automated technologies and indeed, technologies in general, are inherently good or bad is difficult to determine. A hammer can be used to rob a bank and used to hammer in nails as part of a DIY project. The same may apply to new automated AI technologies: whether they are good or bad depends on how we use them.

Figure 3: A variety of service and delivery robots are demonstrated in the Smart Cities Experience Centre in Milton Keynes.

Figure 3: A variety of service and delivery robots are demonstrated in the Smart Cities Experience Centre in Milton Keynes.

Cities have been subject to successive waves of socio-technical innovation. These AI-enabled automated technologies are only the latest in a long line of urban technologies. For example, during the last decade sensor networks and big data hubs have been installed in many cities under the auspices of ‘smart city’ developments.

However, while it is tempting to think that AI is the next step in a data-based socio-technical trajectory embodied in smart city initiatives, AIs are quite different to smart city developments and raise particular challenges requiring planning and governance responses.

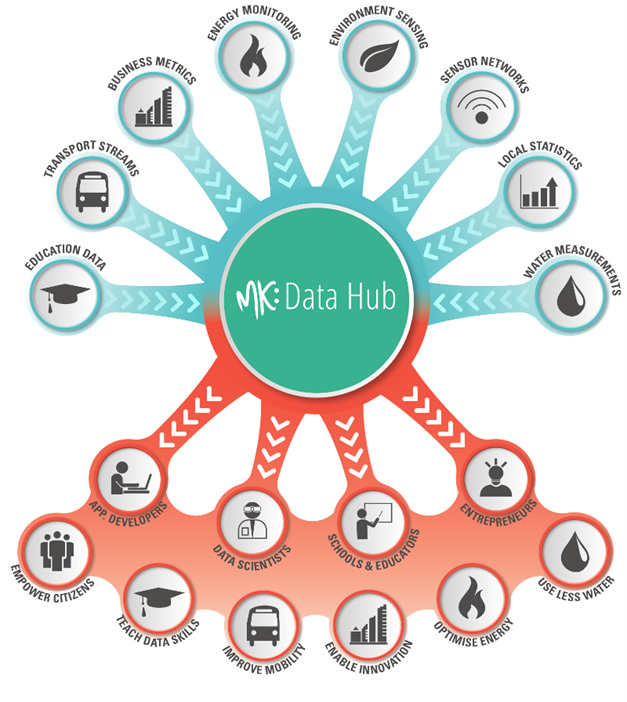

Figure 4: The MK:Smart Data Hub was designed as a data platform for the city with datasets including local and national open data, data streams from both key infrastructure networks (energy, transport, water) and other relevant sensor networks (e.g. weather and pollution data), data crowdsourced from social media and mobile applications.

Figure 4: The MK:Smart Data Hub was designed as a data platform for the city with datasets including local and national open data, data streams from both key infrastructure networks (energy, transport, water) and other relevant sensor networks (e.g. weather and pollution data), data crowdsourced from social media and mobile applications.

First, smart city developments provide data to human actors in urban governance networks for decision-support purposes. In contrast, AI-based technologies draw upon all manner of data to learn, make decisions and act – under human supervision or otherwise. Thus AIs cannot be ignored as without human oversight they may restructure cities in ways not to our liking.

Second, artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics may pose significant practical challenges for urban governance around issues of justice and sustainability. For example, the assumptions such technologies embody in terms of access and availability give rise to a series of pressing issues – which technologies are designed and deployed? How may they inflect and reshape urban environments? Who decides and has ongoing oversight of such urban developments?

Practically, institutional capacities need to be built which enable us to live well with urban AIs and robotics and deliberate, perhaps through their design, what kinds of more sustainable urban futures we may want to attain (and avoid) with these automated technologies. Here, we need to be mindful of the urban inequalities urban AIs may develop and the existing ones they may reinforce; their voracious appetitive for digital data may only further embed smart city developments about which so many concerns have been raised about the ethical use of data. And finally, as many urban AI and robotic systems originate from environments such as factories and warehouses we may need to resist planning and designing new developments promoted in the name of sustainable transport that facilitate the efficient functioning of urban AI and robotics but resemble industrial environments. As with each new wave of urban technological change, we have to preserve the profoundly human characteristics of cities and realise the benefits new technologies such as urban AIs may bring.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews