For a shorter introduction to the geography of tax avoidance, listen to the following podcast.

If you would like to know more, you can read the following extended version:

Little would seem to link the Cayman Islands, Crickhowell in Powys (Wales), U2, and a ‘Double Irish-Dutch sandwich’. But if you type these names into Google and click ‘Search’, in less than a second you’ll be looking at a string of results: ‘Let's all follow Crickhowell and move our businesses 'offshore'’; ‘Bono's hypocrisy on Africa, corporate tax avoidance in Ireland’; ‘The Tax Attraction Between Starbucks and the Netherlands’. A quick read reveals the link: taxation; specifically, ways to reduce taxable profits and the use of so-called offshore tax havens to help realise this goal.

Let’s start with Crickhowell. The connection to taxation stems from this Welsh town’s residents' ‘quest to shame tax avoiders’, which was the subject of a BBC documentary in early 2016. As one of the participants, Irena Kolaleva, told reporters, they had started their question by trying to find out how the use of offshore tax havens works. “Now we've got a moral obligation…We want to bring attention to the problem. It is very simple. If a company is based in this country and employs people in this country, who pay their tax - normal people paying their tax - why do they use legal loopholes paying their tax abroad?" Irena’s question teases out a number of others, from the apparently simple sounding “Just how do ‘offshore’ schemes work?”, to questions invoking big concepts like social justice and the morality of tax avoidance – and they all, well, nearly all, involve questions about geographies, how those geographies are made and their consequences. The task of revealing what the tax expert Richard Murphy calls the ‘secrecy world’ of finance (and its geographies) raises more questions than answers.

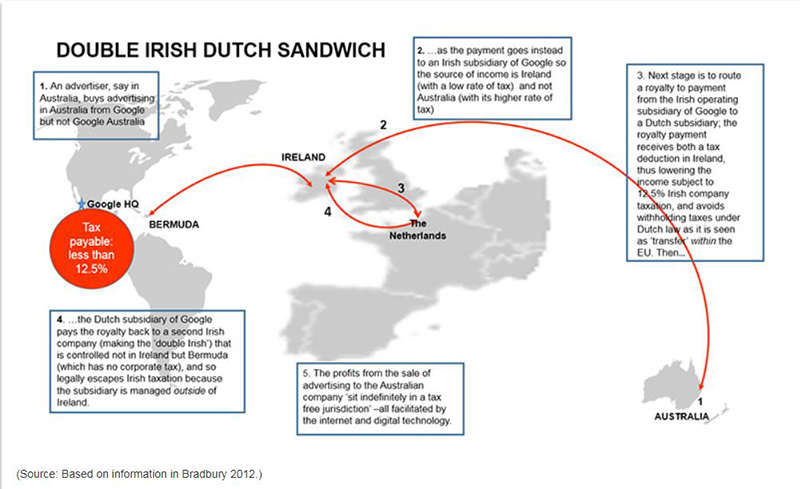

There’s an irony of course in using ‘Google Search’, and it won’t have been lost on you if you’ve been following the news over the past few months. Google itself benefits from tax structures that link Ireland, the Netherlands and Bermuda (another offshore ‘territory’). Recent estimates suggest that the use of this network has enabled the company to boost further its offshore ‘cash mountain’ to more than £30bn.

The image above illustrates a recent avoidance tactic employed by Google in Australia, the workings of which were outlined at a tax conference in Sydney by the Australian Assistant Treasurer, David Bradbury. Bradbury took the unusual step for a political figure in naming Google and its employment of a system called the “double Irish Dutch sandwich”. The sandwich is a tax avoidance technique that uses three ‘rounds’ of shell companies to move profits from Australia, a high tax jurisdiction, to a low one, Bermuda. The name comes from the way the profits are ‘moved’ through jurisdictions and loopholes from one Irish company, then on to a Dutch company and finally to a second Irish company headquartered in a tax haven. This revenue transfer, through a three-stage series of ‘financial shuffles’, allowed Google to end up paying less than 12.5% on the transaction overall (Bradbury, 2012).

Evidently, the potential gains to corporations that result from distributing their revenue through various regulatory spaces, are enormous. And it’s not just Google: Apple, Microsoft, Starbucks… all use similar schemes.

In the UK, where corporate tax is 20%, recent estimates suggest that 100 FTSE companies use 8000 tax haven registered companies to lessen their corporate tax bills; the same estimates suggest that some £20bn per annum in lost taxes results from the use of offshore tax avoidance schemes – roughly the same amount that will be cut from Government departments over the next four years (BBC, 2016).

The movements and flows outlined above and captured in Figure 1 suggest a series of geographies essential to the profits of Google, Microsoft and other major corporations. Yet these are a qualitatively different kind of geography to that traced as the same corporations design, build and distribute their products. Apple, for example, although HQ’d in California, conducts its business across the globe from Europe, to India and Asia, develops its products mainly through US-based research and development; it sources the materials and components from across the globe; assembles the finished products in China and then distributes them throughout the world via distribution centres headquartered in the United States and Ireland.

Both the taxation and production geographies are clearly ‘global’. The latter though, it’s tempting to say, is a geography made through tangible territories, the solid ground housing, say, the assembly plant in China, trackable through the physical export of iPads, iPhones and so on from China to the USA. Stuff, ‘real’ stuff, moves from one territory to another across national borders. The other geography, the one that enables tax avoidance, is slightly trickier to pin down, despite what Figure 1 might suggest.

For although tax avoidance involves places that can be located on a map – the Caymans, Ireland, Holland - this secret world is more virtual than real, enabled not just by communication networks, but by tax jurisdictions and regulations and, significantly, the loopholes in both discovered and created by accounting and legal specialists. This is a geography innovatively shaped by a different set of cartographers to those who lay out the routes for the physical production of, say, Apple’s computers. The cartographers of tax avoidance are highly paid specialists: tax lawyers and barristers, accountants and financial advisors offering discreet, bespoke advice, as well a host of advisors and consultants dedicated to the offshore business.

This is an important reminder of some of the key social relations involved in the secret world of finance and tax avoidance. As the social anthropologist Bill Maurer reminds us: “the claim that pure geography creates [tax] havens conceals the social conditions and actions necessary to the establishment of any financial agreement. Such things do not arise, by themselves, out of the soil” (Maurer 1995, p.135). This brings us back to Irena Kolaleva’s question at the start of this essay: ‘Why do corporations use legal loopholes paying their tax abroad?’ Well, because they can and they can do so legally because current politics produces the enabling legal and accounting framework that renders such movement legitimate.

Finance moves through its secret geographies not simply courtesy of computers, but because the current dominant politic climate legitimises the mobility that creates opportunities for tax avoidance. And the benefits for corporations are significant. For the rest of us, for society, the benefits are less clear. If, as an economist from the IMF has argued, offshore tax arrangements act as ‘fiscal termites gnawing at the foundations of national tax systems’ (Tanzi, 2000,p. 4), then wider society stands to lose out. Arguably then, offshore schemes work to heighten inequality within and across societies. For me, this suggests that just how offshore operates and for whom should be less secret and instead open to questions that involve moral arguments and questions of social justice. In other words, the broader politics of finance and its geographies.

Further Reading

The Open University textbook Material Geographies: A world in the making covers offshore finance in Chapter 3: ‘Making finance, making worlds’. For Open University students, this is part of the module ‘Living in a globalised world’ (DD205).

The article referred to the following articles and programmes:

BBC (2016) ‘Britain’s trillion pound island – Inside Cayman’ [Online]. (Accessed 15 March 2016).

Bradbury, D. (2012) ‘Towards a fair, competitive and sustainable tax base’ [Online]. (Accessed 15 March 2016).

Hakim, D. (2014) ‘Europe Takes Aim at Deals Created to Escape Taxes: The Tax Attraction between Starbucks and the Netherlands’, New York Times, November 14th [Online]. (Accessed 15 March 2016).

Maurer, W. M. (1995) ‘Complex subjects: Offshore finance, complexity theory, and the dispersion of the modern’, Socialist Review, vol.25, no. 3 and4, pp. 113-45.

Tanzi, V. (2000). ‘Globalization, technological developments, and the work of fiscal termites’,IMF Working Paper, vol. 38, no. 1.

Rate and Review

Rate this audio

Review this audio

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Audio reviews

It is reported Hammond is planning on adjusting the VAT threshold next budget, he has two options make it very low say £25k to bring virtually every tradesmen into paying vat or raise it to say £500k to take all sm.all businesses out of vat altogether! The second option is the one that would do most to eliminate the black economy as there would be no advantage in paying cash to avoid vat as it wouldnt be charged anyway. The maths are too complex for this small comment but the tradesman pays the vat anyway to his large supplier, the saved vat is only that in the labour or profit element. Sadly I don't think Hammond is bold! In addition whilst there is much fuss made of say Starbucks avoiding tax it can't avoid the tax on its uk employees nor the rates payable on the shops, even with the avoidance such companies are met contributors to society not least in generating jobs. Thank goodness this is not a tma as my structure is poor but I hope my point comes across! Keep up the good fight Barry Morgan