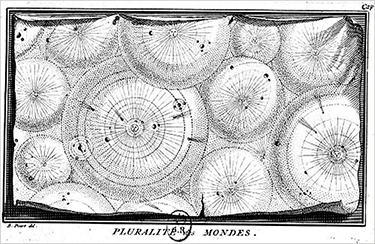

1 A plurality of worlds

Before looking at equity’s foundations in contemporary law there is an important problem to address – namely, that there is no one definition of equity – it is not homogeneous. Rather, ‘equity’ incorporates different ideas and concepts, including justice, fairness and even equality. It is therefore heterogeneous and embraces a plurality of different legal and non-legal worlds. Important for the following discussion is that it is in part due to this diverse or heterogeneous character that equity is able to operate beyond narrow legal considerations and penetrate wider socio-political and economic discourse. But, as will be discussed in the later sections of this course, just because equity has traditionally represented a range of different and largely virtuous ideals such as fairness, does not mean it continues to do so. [To further explore definitions of equity and other words in the course, search for the term in the Oxford Reference collection.]

Gary Watt claims that it ‘is true that equity, like charity, cannot be wholly contained within the confines of systematic general law, but this is not because these ideas lack coherent meaning, it is simply that these ideas have meanings which go beyond meanings that can be categorised in general law’ (2012, p. 8). In other words, something of equity – we may choose, for example, to refer to its ‘essence’ – escapes concrete or settled definitions. F. W. Maitland, who defined equity largely in terms of the historical development of its rules and doctrines, noted the variability of equity’s character. In the opening pages of his famous course of lectures on equity delivered at the University of Cambridge at the turn of the twentieth century, he had this to say on the matter:

What is Equity? We can only answer it by giving some short account of certain courts of justice which were abolished over thirty years ago. In the year 1875 we might have said ‘Equity is that body of rules which is administered only by those Courts which are known as Courts of Equity.’ The definition of course would not have been very satisfactory, but now-a-days we are cut off even from this unsatisfactory definition. We have no longer any courts which are merely courts of equity. Thus we are driven to say that Equity now is that body of rules administered by our English courts of justice which, were it not for the operation of the Judicature Acts [1873–75], would be administered only by those courts which would be known as Courts of Equity.

This, you may well say, is but a poor thing to call a definition.

How to deal with a lack of a concrete definition

It is proposed here that you embrace equity in all its heterogeneity, because to do so is to acknowledge equity as a manifold idea that will in turn provide richer meaning to both law and wider social discourse. There are two main forms of equity you are asked to consider.

First, equity as a division or branch of private common law (distinct from public and criminal law), comprised of rules, doctrines, principles and procedures that are largely occupied with matters relating to private and commercial property in its many and variegated forms. This will generally be referred to here as the ‘law of equity’. This is the form of equity referred to, for example, in law reports. It is also the body of doctrine expected to help counter different forms of opportunistic behaviour using various remedial strategies – for example, injunctions.

Second, there is equity that enfolds a range of virtues such as fairness, equality and justice, as well as being associated with other broader idealised or utopian notions – that is, how individuals and communities ought to live in better, fairer and more equal ways. As a collection of virtues that expect or demand something better, this ‘equity’ will be considered in terms of its capability to disrupt normative social conditions and practices, including mainstream legal reasoning. This radical twist to equity equates in part to Davina Cooper’s ‘everyday utopias’:

Everyday utopias don’t focus on campaigning or advocacy. They don’t place their energy on pressuring mainstream institutions to change, on winning votes, or on taking over dominant social structures. Rather they work by creating the change they wish to encounter, building and forging new ways of experiencing social and political life.

As with the law, equitable ideas often concern private property and how, for example, it is held (possessed, owned), used and (re)distributed in capitalist societies.