5 Bias in judicial decision-making

Up until this point, this course has been primarily practical, focusing on the nitty-gritty of doctrinal law, how judges make decisions, and how understanding these provides tools to answer practical problem questions that are commonly asked of law students to help them develop their legal skills and knowledge. But now you have a working understanding, we are now in a position to look at a deeper socio-legal issues of bias in legal reasoning.

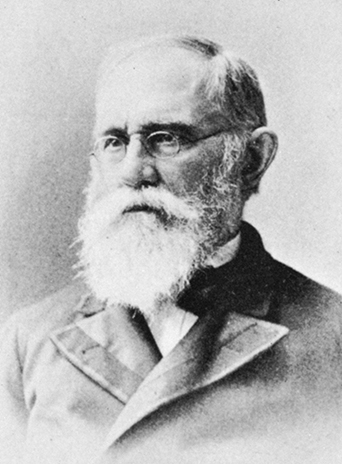

At one extreme, some doctrinal lawyers (lawyers who study the rules and principles) believe that the cases and statutes that form part of the black-letter law always provide the answer, and that judges have very little discretion as to how they decide a case. This view is sometimes called ‘formalism’ and is associated with academic lawyers such as Christopher Columbus Langdell, dean of the Harvard Law School in the late 19th century. If the law does not leave a judge any discretion, then it seems there is no scope for bias to creep in. The law is the law and it does not matter who the judges are (Holland and Webb, 2019, p. 129). Formalism is sometimes called ‘the official theory of judicial behaviour’ because it gives the impression that adjudication is not political (Posner, 2008, p. 41). This can be attractive to a judge who wants to avoid controversy.

But in the 20th century, a group of American lawyers, many of whom were also practising lawyers began to question the neutrality of law. At the other extreme, Felix Cohen called doctrinal law ‘transcendental nonsense’ because he thought it was ‘entirely useless’ for predicting how a judge would behave (Cohen, 1935). They were called legal realists, because they sought a more realistic picture of law. If judges do have freedom to decide cases, it may be important who the judges are.