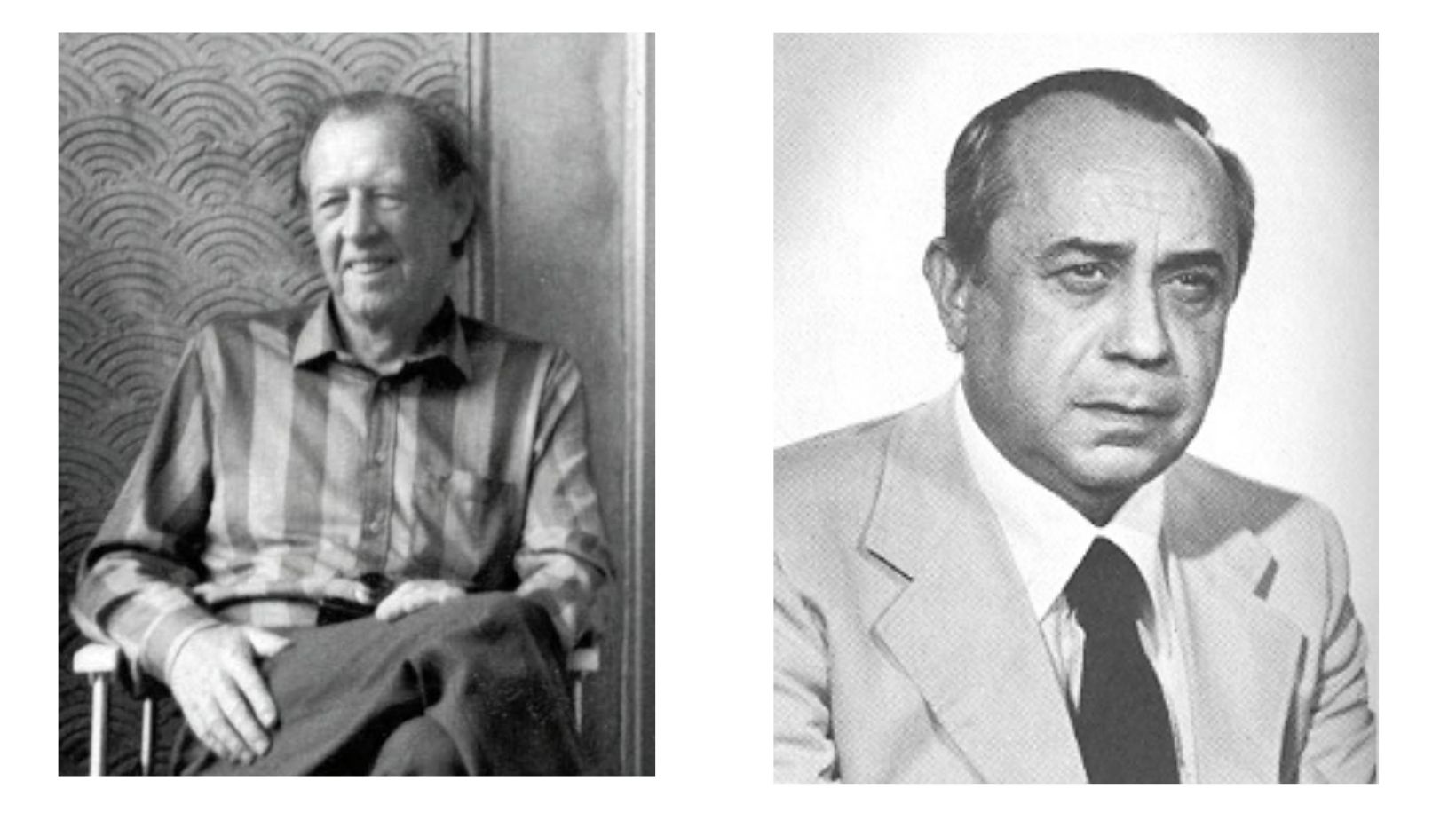

Raymond Williams and Leonardo Sciascia

Raymond Williams and Leonardo Sciascia

This year marks the centenaries of Raymond Williams and Leonardo Sciascia, two outstanding intellectuals, critics and novelists. As intellectuals of the left, their overriding focus was on the contours of modern societies: the cultures, democracies and centres of power. Their work brought them global reputations but the starting points, the essence of their writing to which they always returned, was life experience drawn from the margins and across the borders of different worlds.

Their work brought them global reputations but the starting points, the essence of their writing to which they always returned, was life experience drawn from the margins and across the borders of different worlds.Raymond Williams’s early experiences in his village close to the Wales-England border were recurring themes in both his fiction and non-fiction writing. His father, a railway signalman, was a key source for his early novels, notably Border Country, while his intellectual formation as a Welsh student who became an academic in the cloistered environment of Cambridge University informed his ground-breaking work on culture.

Leonardo Sciascia was from Racalmuto, a small working-class town located deep in the hills of the Sicilian province of Agrigento, where his father worked in the sulphur mines. That environment, its people, land and territory, remained an enduring preoccupation in his work. It was a place he never really left, apart from brief periods in Rome, Palermo and later as a member of the European parliament. His book, Le Parrocchie di Regalpetra (published in the English edition as Salt in the Wound) was based on his experience as a schoolteacher in his hometown. His descriptions of poverty, fascism, and corruption in the Church and town hall were based on real events and became dominant themes in his later writing.

Education informed their respective interrogations of wider cultures. Williams’s writing on culture was influenced by the students in his extra mural classes in Sussex as much as his younger, more affluent Cambridge undergraduates. Some of the best work of both was produced in the late 1950s and early 1960s when post-war European societies were defined by the growth of working-class popular culture, the expanding role of the state and the constraints of the Cold War. Williams’s seminal Culture and Society, an appraisal of the UK’s literary history was published in 1958, the same year that his essay ‘Culture is Ordinary’ appeared. His argument that culture involved the ‘everyday’, that it was ‘lived’ and was increasingly significant within the expanding spheres of film, television and advertising, was advanced a couple of years later in The Long Revolution, which maintained that these cultural transformations would be a match for the democratic and industrial revolutions that had gone before. Sandwiched between these two works was Border Country, his novel rooted in the Black Mountains of his early years and the changes experienced by a young man who after leaving his hometown community for London, returned to find it still recovering from the General Strike and the Depression.

Williams and Sciascia belonged to the left-wing anti-fascist generation of the 1930s and were members of their respective communist parties.In the same period, Sciascia followed Le Parrocchie di Regalpetra (1956), with Sicilian Uncles (1958), a collection of novellas depicting the exercise of power at pivotal moments, including the Allied invasion of Sicily and the prospects for the island’s future seen through the contrasting (and illusory) spectacles of American and communist Sicilians. However, it was The Day of the Owl (1961), that won him most recognition by bringing the Mafia – whose existence was then still denied by politicians and criminals – to a wider public. Through Captain Bellodi, the northern Italian police investigating officer, he explored the culture, mentality and political contexts in which the Mafia thrived, and set out the familiar scenarios in which they operated. In this and his other short detective novels (often inconclusive and without happy endings) he suggested that to understand the Mafia you needed to know Sicilian history and culture.

Williams and Sciascia belonged to the left-wing anti-fascist generation of the 1930s and were members of their respective communist parties. Williams, who was an undergraduate comrade of Eric Hobsbawm, did not stay long in the small British party. But he became a pivotal figure in the New Left that emerged out of the divisions in the communist world in 1956, and which produced much influential analysis of advanced capitalism in the West. He was one of the main authors (along with Stuart Hall and E.P. Thompson) of the May Day Manifesto, published on the eve of the student and worker unrest of 1968, which put forward a radical critique of contemporary capitalism in the period of the Harold Wilson Labour governments.

Statue of Sciascia in Racalmuto

Statue of Sciascia in Racalmuto

Sciascia, as with many post-war Italian intellectuals (including his friends Italo Calvino and Pier Paolo Pasolini), was a member of the mass Italian Communist Party (PCI), and at one point was a Palermo city councillor elected on its ticket. His hopes for Sicily, rooted in the Enlightenment’s pursuit of truth and the search for a sense of state, is often contrasted with Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s brilliant novel, The Leopard, in which the island’s long history of domination by foreign powers gave rise to unrelenting fatalism about its future prospects.

As genuine intellectuals they were unsuited to the alignments and loyalties of political parties (Williams spent a solitary year in Plaid Cymru in the late 1960s), but in their advanced years became more active in public debates.As genuine intellectuals they were unsuited to the alignments and loyalties of political parties (Williams spent a solitary year in Plaid Cymru in the late 1960s), but in their advanced years became more active in public debates. For Williams, a frequent book reviewer, essayist and broadcaster, some of his most original thinking can be found in Politics and Letters, a series of interviews with New Left Review in which he expanded on his interests across drama, literature and politics. One of his last novels, Loyalties, drew on his reflections of the predicaments, betrayals and divided allegiances that faced some of the 1930s generation: another account which extended across the borders of his different worlds.

In the 1970s and 1980s Sciascia, who like his friend Pasolini left the PCI and aligned with the small, contrarian Radical Party, came to greater prominence with his critique of power and corruption during the ‘years of lead’ when the Italian state was held ransom by terrorists of left and right, and further compromised by the violence of the Mafia. In The Moro Affair, his own investigation of the Red Brigades’ kidnapping of former prime minister Aldo Moro – and an incisive demolition of Giulio Andreotti and other leading Christian Democrats, a decade before their party fell into oblivion - Sciascia was unforgiving. ‘Neither Moro nor the party he presided over ever had a sense of state’, he reminded Italians. ‘Indeed, what attracts at least one third of the Italian electorate to the Christian Democratic Party is precisely its total, reassuring – not to say – invigorating lack of an idea of the state’.

As intellectuals from the margins, Williams and Sciascia continue to inspire. Williams liked to see himself as a ‘Welsh European’, a description that has been growing in the aftermath of Brexit and debates over the future of the UK. Sciascia once described Sicily, an island on the boundaries between Europe and Africa, as a ‘metaphor of the modern world’. That description has perhaps never been more relevant, with the questions of justice, reason and state security he first raised in a Sicilian context now at the heart of many global predicaments in the era of mass migration, international criminality and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews