1 International human rights: an introduction

There are many examples of claims for rights in the international sphere.

One example was reported in September 2002. The British government was asked to make efforts to have a British man held by the Americans at Guantanamo Bay deported to Britain to face charges of terrorism there in connection with the attacks on 11 September 2001. Concerns were expressed about the denial of this man's human rights at Guantanamo Bay. Are alleged terrorists entitled to human rights? Can the denial of their human rights be justified on any grounds?

Another example, from around the same time, concerned a woman in Nigeria who faced death by stoning, once she had weaned her baby, after being convicted of adultery. In another case a teenage single mother was given 100 lashes for adultery, even though she claimed that she had been raped by three men. The court ruling in this case said that the woman ‘could not prove that the men forced her to have sex’ (The Guardian, 20 August 2002).

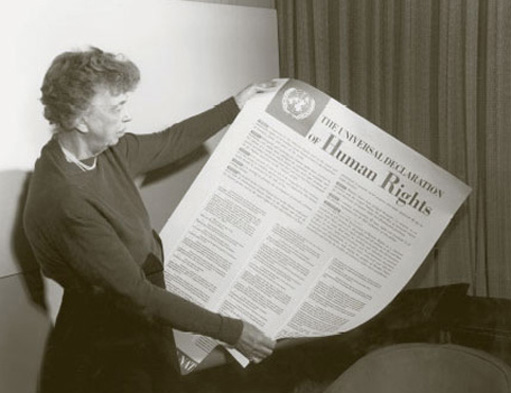

We can hardly imagine the novelty of the idea of universal human rights embodied in the Charter of the United Nations and subsequently codified in the United Nations’ (UN) Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. A radical change occurred in the vocabulary of international politics with the adoption of the Charter, the 1948 Declaration, and later conventions clarifying and extending the notion of human rights. The UN Charter (including the 1948 Declaration) was an important part of the international post-war settlement and it established the UN as an organisation devoted to peace and security alongside human rights and the rule of law. So many states have joined the UN, and signed its Declaration and later conventions, that this has had the effect of consolidating the concept of rights, both the right of peoples to national self-determination and individual human rights.

The 1948 Declaration, in particular, establishes a powerful moral claim for individual rights. It asserts that each individual matters, deserves to be heard, and must not be silenced. Each individual deserves respect and is entitled to be treated with dignity, regardless of their race, gender, creed, colour or mental capacity. The Declaration utilises a common, universal moral language to specify its principles and norms, and signatory countries have come under pressure to implement those rights. Once codified and interpreted, rights become normative.

At the same time, the Charter expresses the intention to recognise the right to national self-determination and the corresponding principle of sovereign equality among the different peoples of the world. Indeed, the ideas of ‘rights’ and ‘culture’ are closely linked in that the advocacy of individual human rights is tied to the notion of the right to ‘self-determination’ for peoples and to statehood for national cultures. The political identity of a national community is an important part of its culture, but different groups in society perceive it differently, depending on their wealth, social position, cultural background, gender, geographical position and age. Furthermore, different national cultures have different political identities. The language of rights and justice is one of the commonest ways of articulating political disputes, and of negotiating rival claims. In short, claims and counterclaims to rights (and justice) take place within national and now international cultural communities.