Technology and art have always been connected, from the first tools and pigments used to make prehistoric cave art, to the present-day questions that artists ask of our relationship to the world around us. Technology has had a huge impact on what the human eye can see, using the properties of the lens to make scientific instruments that extend our gaze out to the stars and down to atoms. Perhaps we don’t spend much time thinking about how we capture images from light through a lens, but it has taken hundreds of years to move from seeing through a lens to keeping the results. That is the breakthrough of photography: a permanent, and portable record of a moment in time, ‘writing the light’. This is how we're able to share a view through a lens. Since the first photographs, the technology for keeping images seen through a lens has moved from chemical to electrical, but the questions about how we interpret images are, if anything, becoming more complex to answer.

...it has taken hundreds of years to move from seeing through a lens to keeping the results.The history of looking through a lens has a surprisingly old beginning. The discovery of how to polish a clear stone, known as rock crystal, was made thousands of years ago, probably by artists looking for new ways of making decorative art who enjoyed the effects of light being bent by curved surfaces. Bronze Age objects that have optical qualities have been excavated in Crete, at the Palace of Knossos (c. 1400BCE) and other sites, including the city of Troy (c. 2,200BCE). The Nimrud lens, from the Palace of Nimrud (Kalhu), Assyria (North Iraq) now in the British Museum, dates back to 750BCE, and is a rock crystal ground and polished with one slight convex face. It is slightly magnifying, but there is no other evidence that the Assyrians used lenses, so it is probably a decorative glass inlay. It is more certain that the ancient Romans knew about magnification: glass lenses have been found able to magnify about two and a half times (2.5x).

A portrait of Gennadios on a medallion

What did they use lenses for? Some suggestions are that magnifying glasses were needed to create the fine detail on distinctive miniature gold-glass portraits e.g. Portrait of Gennadios. However, Ancient Greek and Roman science did not understand refraction (how light is bent through a lens) and did not use lenses to correct short sight (they thought the eye sent out beams, rather than receiving light waves).

A portrait of Gennadios on a medallion

What did they use lenses for? Some suggestions are that magnifying glasses were needed to create the fine detail on distinctive miniature gold-glass portraits e.g. Portrait of Gennadios. However, Ancient Greek and Roman science did not understand refraction (how light is bent through a lens) and did not use lenses to correct short sight (they thought the eye sent out beams, rather than receiving light waves).

The history of optics began in the 1200s CE, with the invention of spectacles to correct vision; this life-changing breakthrough emerged through parallel developments in China and Italy. As lens making became more accurate, artists began to realise the possibilities for using a lens to help with making an image, at the same time as they asked questions about the effects of light on how we interpret what we see.

This matters if you want to paint a realistic human figure; the Renaissance artist Piero Della Francesca made detailed measurements to understand how to translate three dimensions into flat paint, using a technique of plotting points on a model which is still used in CGI filming techniques. This artistic breakthrough is the invention of perspective, which puts painted objects into a convincing relationship with each other: a room filled with furniture and people that looks similar enough to a ‘real’ space filled with solid objects. Leonardo da Vinci wrote about the phenomena of light on surfaces, understanding that different intensities of light on a human face vary with the angle that the light strikes; these observations were formalised in the 1700s as a natural law, now used in computer rendering of digital images. Artists have continued to experiment with depicting the world as realistically as possible, right up to hyperreal paintings.

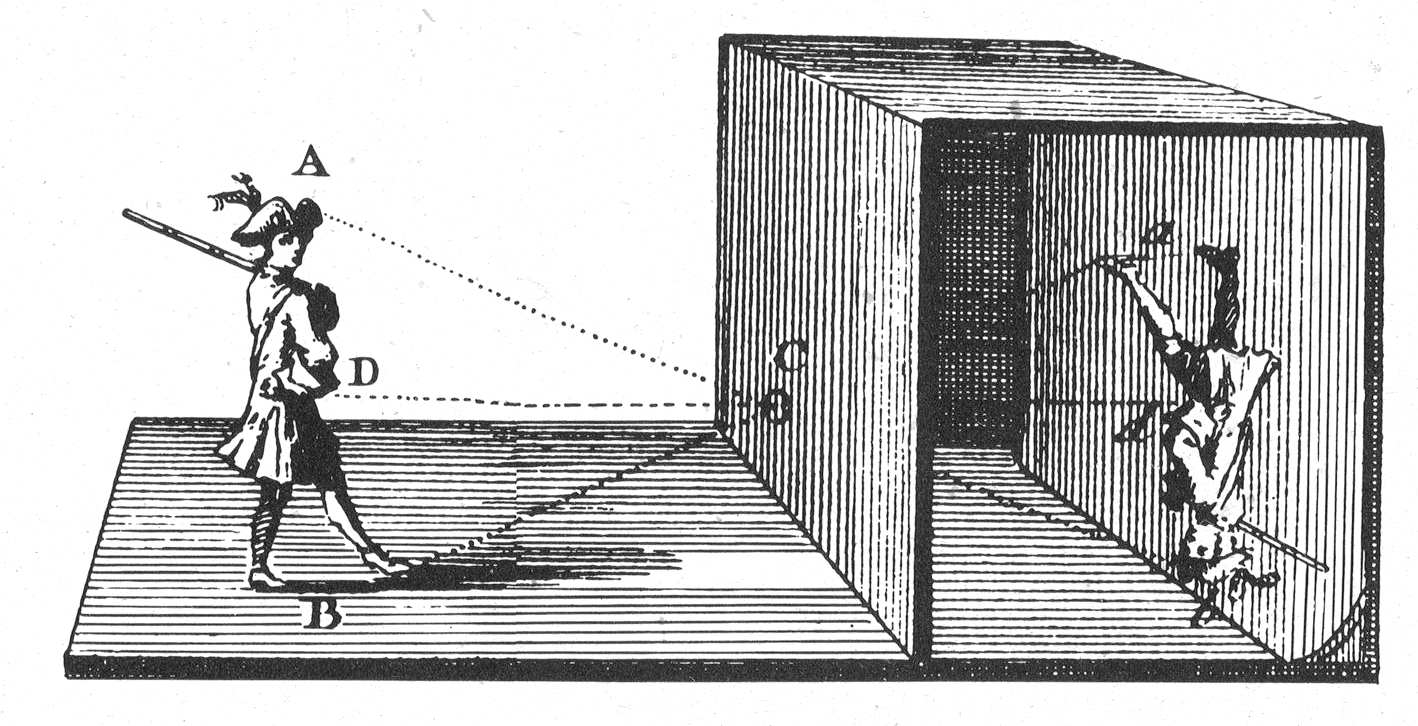

Today we associate cameras with photography, but the first cameras were boxes with lenses, designed to throw an image onto a flat surface in the form of a paper screen. These devices are called camera obscuras, and they are a stage on from pinhole cameras in using lenses. They have been used since the mid-1500s, by scientists, artists and architects to create small images from life, by tracing outlines of the captured image onto the paper screen. One of the best known Dutch artists of the 1600s, Vermeer, used one he called an ‘optical chamber’ to set up the props seen in his paintings as a projection that he could transfer to canvas.

Illustration of the camera obscura principle

Illustration of the camera obscura principle

In 1608 a true telescope was created by Hans Lippershey, using two lenses; from this moment, telescopes evolved through the refinement of their lenses to the deep space telescopes used by astronomers now. Looking beyond our world on the earth has been transformed by looking through a lens.

Understanding how to represent light and space in scientifically accurate relationships changed how objects were drawn, particularly for something that couldn’t be brought into an artist’s studio. The early telescopes, or spyglasses, used one lens to magnify distant objects; in 1609 this gave Galileo a view of the moon with mountains and valleys, a solid landscape. Until then, the moon was said to be translucent because Christian theology linked the properties of light from the moon to beliefs about the beauty of Mary, mother of Jesus; direct observation through a lens challenged this interpretation.

Explorations of the smallest details of life on earth became possible with the invention of the microscope, but as with looking down a telescope, the challenge was to interpret what was revealed. Drawing the observation was an act of interpretation, as well as a means of sharing new knowledge, a painstaking process of repeated looking undertaken by Robert Hooke and published as Micrographia (1665). For the first time, readers could see a flea presented as a complex insect, a ‘minibeast’ of the micro world.

Robert Hooke's flea from Micrographia

Robert Hooke's flea from Micrographia

All of these new ways of seeing, miniature worlds, making images of everyday worlds convincing, and finding new landscapes beyond the earth were contributing to knowledge before the birth of photography, but the crucial difference was the arrival of a chemical means of fixing the fleeting image that appeared through a lens. The arrival of photography did not solve the challenges of understanding what we could now see, but it extended the possibilities of what we could explore.

Explore further: To learn more about the impact lenses have made in our lives, check out our 'Life through a lens interactive' where you will get to explore the history of lenses and more.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews