1.3 Constructing a new image

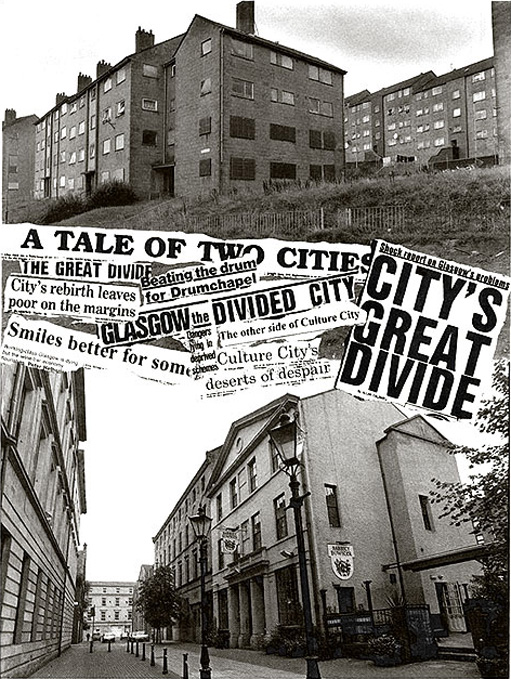

The image ‘Glasgow's miles better’ was deliberately constructed by the City Council, avowedly to make Glaswegians feel better about Glasgow but in fact largely on behalf of business. But it begged a question – ‘miles better for whom?’ Certainly, the city centre was better for shoppers and visitors and the new roads were literally ‘miles better’ for motorists, but the spiralling problems of the housing schemes provided stark counter-images. In other words, as with all images, the image of ‘miles better’ was partial and selective. It was a particular, preferred representation. It excluded other aspects of the city. It was not promoting housing estates like Drumchapel, and they benefited either little or not at all.

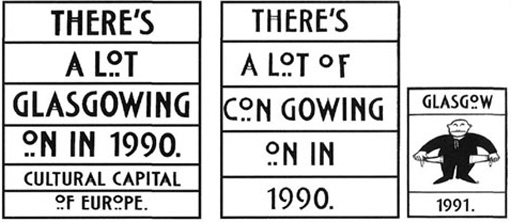

For many people, 1988 marked the arrival of Glasgow on the national scene in Britain, with the National Garden Festival (see Figure 8). For many Glaswegians it proved to be a missed opportunity to gain a lasting amenity, but for those promoting the city it was an important step. In 1990 Glasgow was European City of Culture. By the mid 1990s Glasgow was attracting international conferences (such as Rotary International in 1997 and City of Architecture and Design 1999). But the image of ‘City of Culture’ was particularly strongly contested. On the one hand Glasgow was looking outwards towards Europe in a new way – very different from the late nineteenth and the early part of the twentieth century. From another perspective it was failing to look inwards: the promotion of European and international culture was accompanied by a denial and marginalisation of Glasgow's own local culture. It was also argued that the city would be bankrupted in the process.

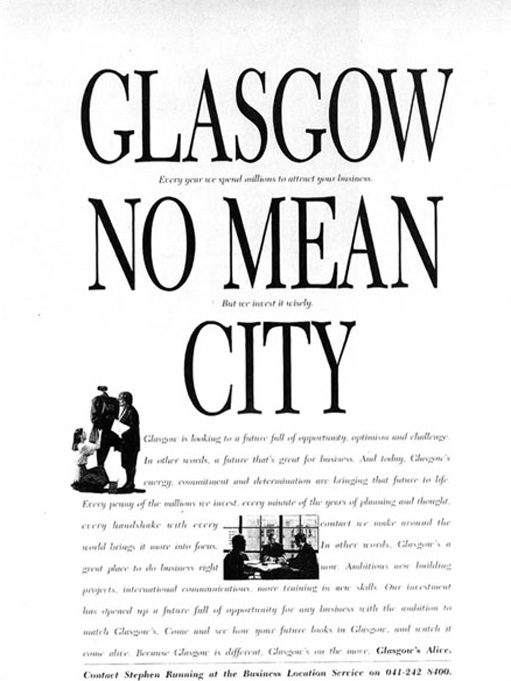

The economy of Glasgow has undergone a major transformation since the inter-war period. In common with many other ‘old’ industrial centres, the majority of the city's workforce is now engaged in service sector employment, a far cry from its image as an industrial city par excellence. In part this transition reflects Glasgow's changing position in both the national and international economies. In the 1980s substantial inward investment in the form of business services and tourist-related activities has further altered its traditional economic base. Public and private sector agencies have been to the fore in promoting the city as a place in which to invest and the dominant image of Glasgow is a much more ‘positive’ one. From being a city characterised by violence and conflict, Glasgow is now marketed by the Glasgow Development Agency's Business Location Service as ‘no mean city’ in which to do business. This demonstrates that the same image can provide different interpretations, in this case one negative and one positive. It also serves to reinforce the point that images are built up over time, providing layers of representations. Contrasting images also illustrate the point that at any one time, more than one image or representation will be available. These alternative images frequently conflict with each other and, in different ways, refer to particular readings of previous histories to portray their messages, some of which may be hidden.

Today's competing images, then, not only compete in relation to contemporary developments and future plans, but also compete in the interpretations of the past of a city such as Glasgow. In Glasgow today, images of a vibrant, modern place, as reflected in the idea of Merchant City, clearly invoke a particular sense of the past. In this respect Merchant City is a particular representation of Glasgow today and one that serves to exclude other images and representations. These contrast strongly with the images of the city's large peripheral housing estates, typified by Drumchapel, which are clearly the product of a very different social and historical context. We can see in this, examples of different ‘envelopes of space-time’, different geographical imaginations. While people in Glasgow often identify with the city itself, different localities within, and competing images of, the city will give rise to different ideas or ‘senses’ of place. Identifying with Drumchapel as opposed to Merchant City or with the city as a whole reinforces the point that senses of place operate at a number of different levels and spatial scales, which may contradict or compete with each other. While spatial or geographical scale clearly refers to identification with particular geographical entities, by ‘different levels’ we refer to the very different class and power relations involved in identifying with a place. It is clear that ‘place’ means different things to different social groups. There are different representations of place at work at any given time, giving rise to competing or contradictory identities with the same place. These, in turn, give rise to counter-claims that the ‘real’ Glasgow is not reflected in Merchant City but in places like the peripheral estates. One of the dominant images to emerge from Glasgow in recent years, then, is the notion of a ‘dual city’: two cities experiencing very different social and economic fortunes in recent decades.

Click here [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] for a larger image.