Find out more about The Open University's History and Social Sciences courses.

This article belongs to the Women and Workplace Struggles: Scotland 1900-2022 collection.

Herring women and girls in inter-war Scotland

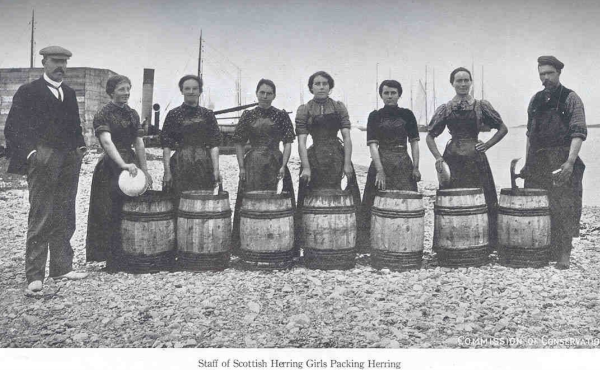

During the 1930s and 1940s a transient group of Scottish women travelled to Great Yarmouth, East Anglia, following the migration of herring shoals down the North Sea. In many of the documents and photographs that are available from the time, these herring women are referred to as ‘the herring girls’ or ‘the Scottish herring lassies’, and ‘Scots fisher lassies’, and in this article Scottish herring women and girls will be used. From the age of 15 women and girls started gutting and packing the herring and travelled from the North and North East of Scotland as far south as Great Yarmouth in East Anglia for work. Scottish herring women and girls became an important part of the workforce within the fishing community throughout Scotland and beyond Scotland to other areas in the United Kingdom (Historic Environment Scotland, 2023).

Following the herring shoals

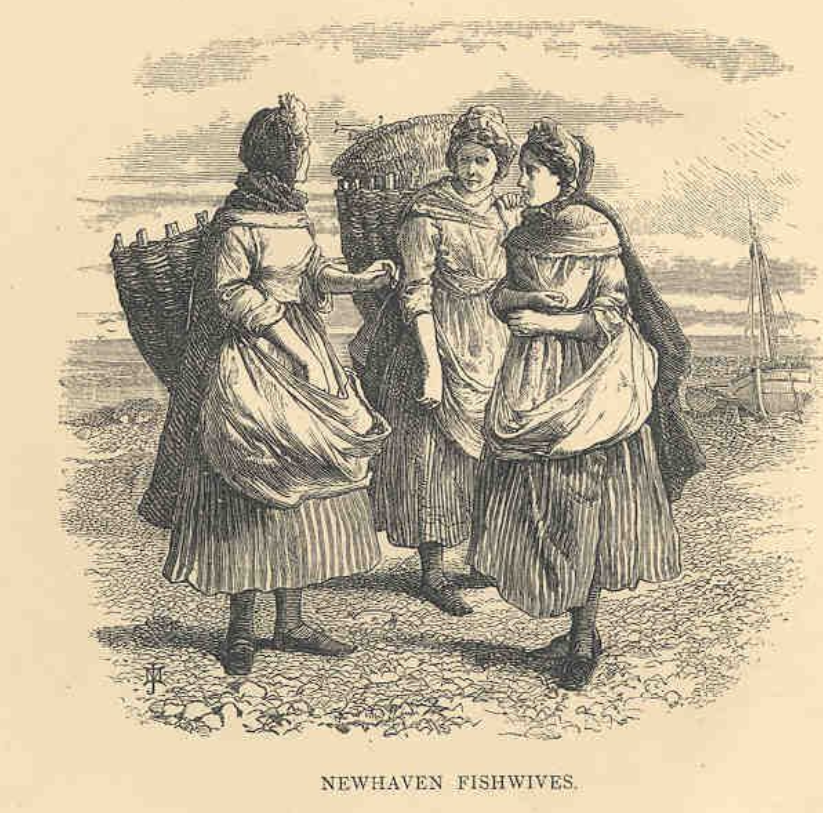

Steam fishing boats were the main vessels used in the Scottish Herring Fleet in from the 1880s. In Scotland, the fishing harbours at Anstruther and Cellardyke on the East Fife coast were the key locations for the landing of herring and the coast around the Firth of Forth became an important herring fishing coastline, with many coastal communities relying on the industry for employment. Women and girls from these communities travelled North to Wick and to the Shetlands for the herring fishing season (Unsworth, 2013). From the late 1860s, women and girls started travelling South to East Anglia in England for the autumn herring season.

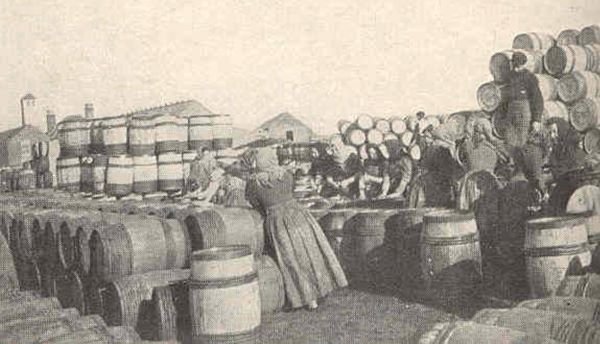

During the early 1920s the fishing industry fell into decline and many fishers lost employment and the Miners’ Strike in 1921 impacted on the availability of coal for the fishing steam trawlers and drifter fishing boats. During the miners’ strike the Fishery Board sent a formal letter to the to the Fishery Officer outlining the impact of the lack of coal on the Herring Fleet in Scotland. In 1914 approximately 35,500 people were involved in the Scottish herring curing industry and almost 14,000 women were employed in the herring industry at this time, mainly in fish gutting and packing (Davis, 2010).

Working conditions and pay

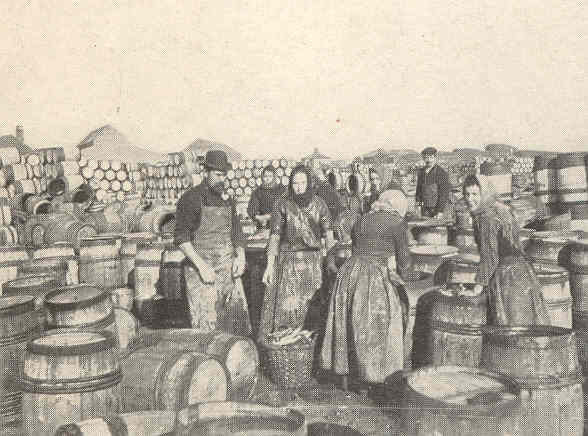

The working conditions were cold and herring women needed to work at speed often cutting their hands and binding their fingers to prevent infection and the salt reaching the wounds. It was physical labour working at speed, gutting the fish and the pay was low:

‘The normal average take home pay for a whole season was about £10 to £12 up to the beginning of the 20th century…’ Angus Macleod, Archive.

In Great Yarmouth during the early 20th Century it was reported that women and girls were woken at 5am to bandage their fingers for the work ahead and herring were gutted at speed over the whole day. Using the special sharp knife, the 'cutag', meant painful nicks and cuts were a frequent hazard.

Scottish herring women and girls packed their clothing, boots, oilskins and blankets into a chest that was called a ‘kist’ as they travelled south. Many herring women were employed by the same herring curer each year and at the end of the summer herring season the curers employed herring women for the autumn months in Great Yarmouth. Fishing communities looked forward to the annual arrival of the herring women and girls.

The herring women worked in small crew teams where two women were fish gutters and the third member of the team packed the gutted herring into salt barrels. It was cold and fast work and one herring was gutted and packed every ten seconds. Approximately 700 herring were packed into a barrel and the crew of three women were often able to pack 30 barrels a day (10-hour day). The Scottish Herring women were involved in starting a strike in 1936 to protest and take action to improve pay.

In November of 1936 the herring industry in Great Yarmouth was brought to a halt when herring women and girls started this pay strike and they can be seen on the archival video footage taking action. This is a rare piece of footage where the women organised the strike and demanded a shilling a barrel for the gutting and packing of the herring. The women and girls can be seen taking strike action saying:

The Scottish herring women took unofficial direct action in Great Yarmouth and 3,000 women went on strike demanding the higher pay of one shilling for gutting a barrel of herring, which was an increase from 10 old pennies a barrel. Herring continued to be brought to shore while the strike continued over the week and the herring women and girls continued to protest and encouraging other herring workers to join the strike (Angus Macleod Archive, 2022). The Transport and General Workers Union then became involved and the strike for increased pay continued over a week. Mounted police were brought from London as detailed within the Angus Macleod Archive.

These official and unofficial protests and strikes by the Scottish herring women and girls has gradually faded from memory as described by historian Sam Davis: ‘these strikes have remained largely ‘hidden from history’, because they do not fit easily into the dominant interpretations of the history of trade unions and industrial relations of the period (Davis, 2010. p.181). When speaking today with fishers in some of the coastal communities on the East coast of Scotland there are lingering memories of the strikes. One of the notable differences between herring women in Scotland in comparison with those from England was that the Scottish women were not allowed to work on a Sunday, such was the power of the established Church of Scotland at the time. There were geographical, religious and economic differences within the transient group of working women and girls. For example, there were economic and cultural differences between women from the crofter and fishing villages of the Western Isles and those from the Shetland Isles and the herring villages and towns along the Fife coast. They became united in the action for increased pay.

Not entirely forgotten

Some memories and stories of the Scottish herring girls continue to linger in Norfolk. The transient nature of their employment, their hard work and long-lasting friendships they established have not been completely forgotten today as stories and memories of the herring women and their strike action were recently posted on social media (Norwich and District Trades Council, 2021). Norwich and District Trades Council (2021) shared details of the strike action where women travelled from Barra and Lewis to Great Yarmouth on trains provided for the fishing industry and within the comments section of the social media posts current memories of the herring women are shared and discussed. The strike of the Scottish herring women and girls are an example of collective action where working women brought about improved working conditions and pay. There will be many unrecorded memories of this direct action by Scottish herring women and girls.

.jpg)

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews