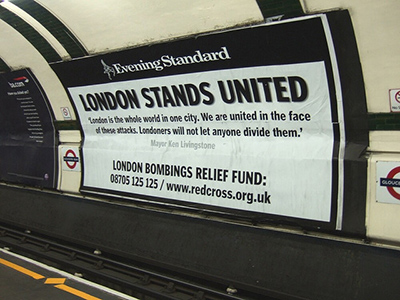

A poster outlining Ken Livingstone's statement

In the numbed days after the first bombs went off on London's public transport in July 2005, Ken Livingstone said 'this city is the future'.

A poster outlining Ken Livingstone's statement

In the numbed days after the first bombs went off on London's public transport in July 2005, Ken Livingstone said 'this city is the future'.

'This city' he said 'typifies what I believe is the future of the human race and a future where we grow together and we share and we learn from each other'. He set London in the wider context of the development of European cities generally, and of cities around the world: 'If you go back a couple of hundred years to when the European cities really started to grow and peasants left the land to seek their future in the cities there was a saying that 'city air makes you free' and the people who have come to London all races, creeds and colours have come for that. This is a city that you can be yourself as long as you don't harm anyone else. You can live your life as you chose to do rather than as somebody else tells you to do. It is a city in which you can achieve your potential. It is our strength and that is what the bombers seek to destroy….'

Livingstone's passion sounded out in stark contrast to the manufactured sincerity of Tony Blair. Nor did Ken speak of good and evil, but of a real grounded politics. His commitment to diversity and hospitality rang a clear note after a general election, some months previously, in which dismally negative debates about immigration and asylum had been prominent. Nor were these sentiments without a basis on the streets. Surveys show Londoners consistently valuing the city's cultural and ethnic mix and seeing that as central to London's identity.

The Guardian, on the 21st of January that year, had published a special supplement: 'London: the world in one city: a special celebration of the most cosmopolitan place on earth' .

In the aftermath of the bombing, the London Evening Standard ran a special edition with the title 'London United', and in Time Out, the front cover said simply 'Our City'.

At the gathering in Trafalgar Square, Ben Okri read a poem he had re-titled 'A hymn to London': 'Here lives the great music of humanity'

The Olympic Bid had been built around claims of cultural and ethnic diversity; there is the Respect (now Rise) campaign against racism.

Nor has this been only a simplistic version of multiculturalism, a claim to some happy harmony – Livingstone's stance since the bombing has been firm in its refusal to bow to pressures for exclusion and repression, and in its determination to continue with criticism where this is thought politically to be warranted. It recognises that this may be a conflictual negotiation of place.

There is evidently much more that could be said about this. Indeed in the months after the bombing 'multiculturalism' became again a contested term. It is also important to register that such statements ('This city is the future') in the singularity of the future to which they lay claim, could themselves be seen as an imperialising gesture – our future is the universal future.

(It is in fact only one possible future, and even if it comes to pass for London and for other places, it may nonetheless exist in a world in which there are other futures too.) I would prefer to read such words, therefore, as a statement of political commitment.

Not just as a description, nor as a claim to be at the front of some posited singular historical queue, but as a statement that London stands for something, a particular kind of future, but carrying with it the possibility that this may be one future in a still varied and plural world. Maybe other places, other cities, will be different.

Advert showing unity in London, 2005

At the moment, however, I just want to draw out one point, which is that that positive attitude towards diversity is claimed to be central to London's identity, is something that a majority of Londoners seem to be quite proud of (and this without ignoring the evident racisms and intolerances which abound), and is to some extent embedded in policy and often drawn upon and celebrated in the arts. It is one of the ways (and in the period around the bombing the dominant way) in which London thinks of itself as a 'world city'.

Advert showing unity in London, 2005

At the moment, however, I just want to draw out one point, which is that that positive attitude towards diversity is claimed to be central to London's identity, is something that a majority of Londoners seem to be quite proud of (and this without ignoring the evident racisms and intolerances which abound), and is to some extent embedded in policy and often drawn upon and celebrated in the arts. It is one of the ways (and in the period around the bombing the dominant way) in which London thinks of itself as a 'world city'.

Moreover it is politically interesting – and heartening – because it is a claim to place that is open rather than bounded, hospitable rather than excluding, as ever-changing rather than eternal. And nothing that follows is meant to gainsay that. What I should like to explore about this imagination of place held by so many Londoners, however, is how it might be broadened out.

First of all this is an internal, indeed internalised, view of the city. It is about hospitality, about those who come to 'us', about the strangers within the gate. However the geographies of places aren't only about what lies within them. A richer geography of place acknowledges also the connections that run out from 'here': the trade-routes, investments, political and cultural influences; power-relations of all sorts run out from here around the globe and link the fate of other places to what is done in London.

This is the other geography – the 'external geography' of a place.

It is a geography that attaches to any place, but it is especially important to a place like London. In recent debates about identity, we have moved away from notions of isolated individuals towards an understanding of identity as thoroughly relational, as constructed through rather than prior to our interactions with others. The same move has been made in relation to place-identity. And yet the way that this insight has been developed has often been to concentrate on the implications for the internal constructions of identity: the internal multiplicities and fragmentations, and so forth. And so it has been with place-identity too: it is a commonplace now that every place is hybrid, that we must be critical of notions of coherent communities.

Yet, there is another geography, that geography of external relations on which identities, including the identities of places, depend. How do we bring that into our attitude to, and our politics of, place? This tendency to inward-lookingness becomes even clearer when we turn to the second reservation about the characterisation of London as multicultural future of the world.

For London is not only multicultural. It is also – for instance – a heartland of the production, command and propagation of what we have come to call neoliberal globalisation. Indeed it was in London that many of its lineaments were first conceived.

The City (capital C), and all the vast and intricate cultural and economic infrastructure that surrounds it is crucial to neoliberalism.

About 30% of the daily global turnover of foreign exchange takes place in London; London has over 40% of the global foreign equity market; and so on.

Meanwhile, the 2005 UN Report on Human Development produces 'the usual' statistics – the kind that are so bad it is difficult to know how to receive them.

The world's richest 500 people own more wealth than the poorest 416 million.

And it is not just a problem of the super-rich: Europeans spend more on perfume each year that the $7billion needed to provide 2.6 billion people with access to clean water.

London is a crucial node in the production of an increasingly unequal world.

When Ken Livingstone speaks of people coming to this city because of the freedom it offers he is right. But people find their way here for other reasons too. They come because of poverty and because their livelihoods have disappeared in the maelstrom of neoliberal globalisation (and millions more are left behind).

And it has to be at least a question as to whether London is a seat of some of the causes of these things. And that raises, in turn, the question of what is our responsibility for those wider geographies of place. Most formulations of the relation between 'local place' and globalisation imagine local places as products of globalisation ('the global production of the local'). It is a formulation that easily slides into a conceptualisation of the local as victim of globalisation.

Here globalisation figures as some sort of external agent that arrives to wreak havoc on local places. And often indeed it is so.

The resulting politics in consequence often resolves into strategies for 'defending' local places against the global. Such strategies in any case harbour a host of political ambiguities, but in the case of London – and of places like London – this simple story anyway cannot hold.

For London is one of those places in which capitalist globalisation, with its deregulation, privatisation, 'liberalisation', is produced. Here we have also 'the local production of the global'. And yet a celebration of multiculturalism and a politics of anti-racism exist alongside a persistent obliviousness on the part of the majority of Londoners to the external relations, the daily global raiding parties, the activities of London's financial sector and multinationals, upon which the very character and existence of London depend.

The current London Plan (produced by the Greater London Authority in 2004) provides a case in point. Here, in consideration specifically of the city's economy, London's identity as a world city is understood in terms of its financial power. Moreover this global financial muscle is presented as a simple achievement. It is not reflected-upon in its intimate relation to imperialism and colonialism.

The Plan presents no critical analysis of the global power-relations that sustain this world-citydom; it does not follow those relations out around the world and ask what they may be responsible for; it asks no questions about the connections between this economic power and the increasing inequalities around the world. Indeed, the Plan has as its central economic aim the expansion of London as a global financial power.

It must be stressed that in this the London Plan is not at all unusual. This is the norm. Thinking about places, including plans for places, nearly always in this sense remains 'within the place'. It is part of the tension between a territorialised politics and a world structured also by flows. But what it means is that, in this city which is indeed in so many ways progressive and even radical, we have, we nurture, the production of the beast itself.

How might a politics of place beyond place be imagined?

Here is one example, which encapsulates a number of the arguments I am trying to make. In part precisely because of the current way in which London is a world city it finds it very difficult to reproduce itself. Public-sector workers and lower-paid privatesector workers can barely survive and a whole range of schemes has had to be devised to enable adequate recruitment.

One thing that this means is that London is massively dependent on labour from abroad, including from the global South. It is dependent, for instance, on health workers from Africa and Asia. These countries can ill-afford to lose such workers, and they have paid for their training. So India, Sri Lanka, Ghana, South Africa are subsidising the reproduction of London. It is a perverse subsidy, flowing to the rich from the poor.

This is a difficult issue because it can so easily be turned around into a racist denial of immigration rights. A 2005 Medact Report (which was concerned with the UK as a whole) suggests, in relation to health workers from Ghana, that the two health systems (Ghanaian and British), including their trades unions, could be thought of as one system and that the UK could pay restitution to the Ghanaian system for the perverse subsidy that currently flows in the opposite direction.

There may be other approaches, but this one is interesting because it changes what otherwise might be thought of as aid to Ghana, with all its connotations of conditionality and charity and the power relations thereby implied, into a matter of the fulfilment of an obligation.

It expressly addresses the issue of unequal external geographies. It is also important because, through this, it forces a re-imagination of place: it looks from the inside out; it recognises not just the outside within but also the 'inside' that lies beyond. At the moment, however, this is not even a live political debate amongst Londoners. It is not an issue that has registered as integral to the identity of this place. We may celebrate the arrival of Ghanaians in London as part of the great ethnic mix. But we do not follow those lines of connection out around the rest of the world and enquire about the effects there.

We need to globalise in some way that local claim to multiculturalism. This small example involves another way of thinking about health professionals but such things are needed to help promote an outward-lookingness, a consciousness of the wider geographies and responsibilities of place. Moreover, within the place, within London, all these things would be disputed – which could only enrich the internal politics of place, multiply the lines of debate around which 'place' must be negotiated. It would challenge the current exoneration of 'the local' within a critical global politics, and begin to develop a local politics of place beyond place.

Doreen Massey is Professor of Geography at The Open University.

This article was used to support the OU / New Economics Foundation event - Interdependence Day - held in July 2006. A longer version of the article appeared in Soundings, Issue 32 Spring 2006.

More on the London bombings

How do you design a memorial for a terrorist attack? That question was explored by an episode of our podcast Changing Approaches To Heritage.

The singular and the collective became a defining sort of phrase that carried us through consultation process. And the concept resulted in fifty-two cast stainless steel ingots, located in this particular special place in Hyde Park, each of these ingots representing a life lost. Now these stainless steel castings are arranged into four clusters, with the number of each life lost at each place forming the numbers of the clusters. And in turn blending those clusters together to form a collective composition of fifty-two elements.

Listen to the full podcast: 7th July bombings memorial

- The Independent remembers each of the killed with a brief biography of each

- Goldsmith's Victor Seidler asks if the different nature of attacks on them explains why New York and London remember differently

- Writing in The Telegraph, Peter Clarke - head of The Met's Counter Terrorism Command at the time - shares his view of counter-terrorism operations

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews