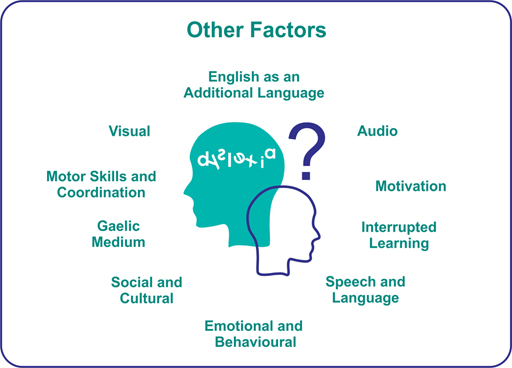

Other factors to Consider

Module 2 highlighted that when starting the process of identification of dyslexia, particularly if the concern has arisen due to difficulties in the acquisition of literacy and language skills practitioners need to explore, indeed rule out other possible factors which can impact on the development of literacy skills, some of which are highlighted in figure 11. Conversely as with the characteristics used in the Scottish working definition, these factors may be areas of strength.

Audio

Audio Processing Difficulties (APD) are one of the associated characteristics for dyslexia and may manifest as difficulties in processing and distinguishing sounds/ syllables/words and identifying where they heard them in words/sentences may have an auditory processing difficulty.

(APD) can affect people in many different ways. A child with APD may appear to have a hearing impairment, but this isn't usually the case and testing often shows their hearing is normal. It can affect their ability to:

- understand speech – particularly if there's background noise, more than one person speaking, the person is speaking quickly, or the sound quality is poor

- distinguish similar sounds from one another – such as "shoulder versus soldier" or "cold versus called"

- concentrate when there's background noise – this can lead to difficulty understanding and remembering instructions, as well as difficulty speaking clearly and problems with reading and spelling

- enjoy music

If APD is suspected then it is important the family consult with a medical practitioner and this should be discussed sensitively with the family.

Motivational factors

Linking very much with health and wellbeing there may be reasons why the learner does not appear to be motivated to engage in particular aspects, or most aspects of learning.

- Health and wellbeing aspects

- Disengagement - Not wishing to appear to be working at a lower level than their peers

- The reading/topic subject matter does not enthuse the learner to persevere – they may have no interest in the topic of the reading book/scheme

This is a very important area because tapping into the learner’s motivational interests and strengths can provide a way forward in developing appropriate support and strategies.

Interrupted learning

Children who miss a significant amount of schooling at important stages for learning, or who have limited language experience may exhibit signs of literacy difficulties due to having lost out on the teaching and learning of specific parts of phonics that are essential for reading, spelling and writing. If this has not been compensated for at home or in later schooling, then this may explain why their difficulties are growing. Lack of ability to read often means that the child does not try to read, and therefore loses out on new learning. This then sets off a downward spiral of poor school experiences that is self-perpetuating.

It will be important to ensure that such factors are taken into account in the observation and assessment process at this stage, and steps taken to ensure that any gaps are identified. This means young people can receive appropriate teaching to make up for the missed areas, or when this is unlikely to be possible to circumvent by providing for example, a text reader that the child can use with earphones on the computer to access whatever text the rest of the class is working on. Specific focused teaching of phonics is not easily embarked on at this stage, so circumvention strategies that will help the child avoid the failure s/he has become used to, are vital. Information should have been recorded regarding gaps in learning on SEEMiS and or recording methods in your school/local authority and you should access this and put in place any necessary steps so that detailed assessment can take place.

Speech and Language

Although not all young children with dyslexia have early speech and language difficulties, there is evidence that many do. Early speech and language difficulties may be indicative of later difficulties in acquiring literacy. Also dyslexia can co-occur with ongoing speech and language problems. Furthermore ongoing language problems may also be associated with reading comprehension difficulties. Practitioners need to be aware of these associations and if there are problems with a child’s speech and language, then early intervention is likely to produce the best outcome for the child.

Children may have difficulty in sounding out words and have problems with phonological awareness. A case history of early development and information about early/previous/ongoing input from Speech and Language Therapy is helpful.

Children with dyslexia may be able to say a word but cannot break it down into syllables and/or sounds. They may have difficulty working out the constituent sounds in a word e.g. they are unable to blend d-o-g to make ‘dog’. For others, their auditory awareness of sounds is impaired, so they are unable to say where in the word a sound comes e.g. they are not aware that the /b/ sound in ‘boy’ comes at the start. For those children training in auditory discrimination is vital if they are to be able to learn phonics successfully.

If there are concerns over elements of speech and language development, then referral to a speech and language therapist is advised for advice and appropriate management. Speech and Language Therapy involvement may be at Stage 1 where there are early speech, language or communication difficulties. Advice regarding Speech and Language Therapy in association with ongoing concerns regarding literacy development may be sought at Stage 2 or 3 of the Staged Intervention process, depending on supports available locally. Referrals can come from a range of different sources, but must always be done with the parent’s consent.

Emotional and Behavioural Factors

There are many factors that will influence how a child adapts and responds to the learning environment. Feelings of failure will affect the child’s learning, so it is important to consider possible reasons for any problems in the behaviour field and try to find ways for the child to succeed. Close liaison with parents will be required to establish if there are factors that we need to be aware of, and take account of in teaching – e.g., in what circumstances does the child respond well? – e.g. Does s/he like to be given responsibility? Who are his/her role models?

When considering dyslexia assessment, it is important to ask yourself why the child is behaving in the way they are as this is not always obvious, and sometimes may be due to the frustrations the child feels when not learning as they feel they should, and seeing a gap between what they can do and what others can achieve. This will be particularly frustrating if that gap is also growing! It is important not to rule out dyslexia because of seemingly “bad behaviour” but to consider learning in a variety of contexts. If the child learns well at some times and not at others, or in some subject areas and not in literacy, and there is no other obvious reason for this, then consider the possibility of dyslexia.

It is important also to work with families on achieving success in some aspects of learning so that children see the rewards for their efforts as well as achievement. Parents can generally give information on how the child is behaving at home, and this may help you decide on the most appropriate strategies to employ to tackle the difficulties. More detail on the types of behaviours that may be observed are considered under the three headings of:

Disappearing Strategies

Children who have a quiet disposition may adopt the strategy of becoming a ‘Disappearing Child’ in the classroom, by being exceptionally quiet and not drawing attention to themselves at all. They avoid eye contact with the teacher and do not put up their hands to ask or answer questions. Many will perfect a performance that makes it seem as if they are engaging in a task appropriately. They will appear to be writing or reading even though they may have a poor grasp of what the task entails or may not have the skills to accomplish the task. In a busy classroom such children may be difficult to identify for a considerable time which means that they may be lagging far behind peers once they are identified.

In some cases a child will develop a strategy that means they are physically not in the classroom when a particular task occurs, most often reading aloud, which dyslexic children find the most frightening aspect of the classroom. This strategy may take the form of being particularly helpful, so the child may volunteer to take the register to the office or to take messages around the school to other teachers. They will perhaps take rather longer than is necessary to complete such tasks in the hope that the activity that they are trying to avoid will be finished by the time they return. Some children use the pretext of frequent and extended trips to the toilet to achieve the same aim. Teachers should be alert to the timing of these activities. Is there a pattern for example in a child’s behaviour that suggests s/he is concerned about a particular task? At the extreme of the continuum of ‘disappearing’ strategies a child may use illness as a mechanism for avoidance so a pattern of absence related to the timetable may alert either teachers or parents to the child’s underlying difficulty.

Distracting Strategies

For dyslexic children who have good verbal skills the preferred strategy is often that of becoming ‘The Class Clown’ – the child who is always ready with a quip or a joke. On the face of it this behaviour is not likely to endear the child to a teacher but it is likely to result in a high level of peer approval and for a child who feels that he is unable to do what the teacher requires, being popular with peers may seem a worthwhile alternative. This strategy also distracts everyone from the task that the child may fear and is an attempt to avoid being seen to fail by the peer group.

If a dyslexic child is skilled at sport then a focus on that activity may also serve to distract teachers from the child’s difficulties with classroom tasks. Such children often maintain high self-esteem and peer group approval despite having difficulties with text based tasks so there is a possibility that engagement in the sporting activity may lead to difficulties in other areas being overlooked.

Disruptive Strategies

If a child does not have the verbal confidence to become the ‘Class Clown’, or the sporting prowess to aim for ‘Team Captain’ status, then being a ‘Disruptive Child’ may seem a reasonable alternative. Again, as adults we can see how misplaced a strategy this is, but children do not have such a long-term perspective and focus mostly on resolving their immediate difficulties. If the dilemma is how to avoid failing at a particular task, especially in front of friends, then standing outside the door of the classroom as a result of obnoxious behaviour is actually a reasonable solution to the immediate problem. Again, children who adopt such behaviour may well be popular with their peers as watching someone else get into trouble is entertaining but presents no personal risk to members of the ‘audience’.

At the extreme of the continuum of disruptive strategies are the children whose behaviour leads to them being excluded or those who play truant in order to avoid the stress of facing tasks in the classroom that they cannot complete. This of course means that they have also, quite literally, ‘disappeared’. Such extreme strategies tend to occur if some of the other strategies have not elicited the recognition and support that the child needs. By this time the child is likely to have developed ‘learned helplessness’ which is a state in which an inability to undertake particular activities undermines confidence in all tasks, even those that could be accomplished successfully. Such children, though rare, are at this stage ‘lost’ to education as they feel no sense of engagement or ‘belonging’ in a context that has failed to meet their needs.

Children tend to be pragmatic creatures. In reality the child's day to day life in the classroom would be easier if s/he simply undertook the tasks presented so we must conclude that if a child could complete text related tasks, s/he would - simply because it is easier to do so. If a child persists in not completing tasks successfully in the classroom then we should assume that there is likely to be an underlying reason for such behaviour. One possible explanation is that the child is dyslexic and therefore needs additional support in order to develop the text related skills required.

By now, the young person will be only too aware that their learning is not as they would like it to be, and it might be expected that dyslexia will have been discussed. If however, the child has not been formally assessed then it is best to delay no longer as the assessment may help the child’s understanding of his/her difficulties, and hopefully behaviour will improve as a result. It is not unusual for behaviour problems at this stage to be considered as the problem rather than embarking on the pathway to full assessment. Assessment however is important for the young person and his/her parents. This will give a reason for the young person’s problems and also a focus for discussing what can be done to improve both the behaviour and the learning.

Motor skills/co-ordination and organisation

Not all children with dyslexia will have obvious difficulties with motor skills, but even slight lack of co-ordination may influence the child’s ability to cope well with handwriting. When motor skills are affected, this often affects self-esteem as the child has difficulty with sports and physical games. Spatial awareness can be a problem resulting in the child being unaware of where on a page to start for writing or reading until this skill has been overlearned.

Organisational skills are often weak in children with dyslexia. This may or may not be related to sequencing abilities, but these also are often affected, meaning that the children have difficulty in recognising order in days of the week, months etc. If the children are disorganised, and/or untidy, then it is unlikely that they will endear themselves to teachers or their peers. However strategies for organisation and sequencing can be learned and the sooner the better for the sake of the child’s self-esteem and confidence.

If there are concerns over elements of physical co-ordination or motor skills development, then referral to an occupational therapist is advised for advice and possible exercises. Referrals can come from a range of different sources, but must always be done with the parent’s consent.

Social and Cultural factors

- Are there social factors that might help explain the child’s difficulty with literacy development?

- Do you know what the child’s experience is of books in the home?

- Does he or she have the opportunity and/or encouragement to do schoolwork at home at all?

- Is the family supportive of the learner’s schooling, or uninterested/ antagonistic?

Sometimes illiteracy that derives from environmental and social factors will mimic dyslexia: poor literacy, impatience with written learning, poor attention, chaotic organisation, attention seeking, etc.

It may make no real difference to the support you provide at school as a learner with literacy needs will require support whatever the cause of these needs’ - whether the causes are intrinsic or extrinsic - within the learner or deriving from the learner’s environment. But it will be useful to be as clear as possible in your own mind what the balance of factors might be.

Visual problems

Poor readers may have motor and/or perceptual problems with vision, and improving vision can have a very positive effect on accuracy, fluency and understanding of text. Though visual problems are not likely to cause dyslexia, if they are present they will certainly aggravate pre-existing difficulties. Examples of the types of problems that may be present are:

Visual Stress/Meares-Irlen Syndrome

- poor vergence control

- scanning/tracking problems and poor binocular vision

Symptoms of visual problems may include:

- eye strain under fluorescent or bright lights glare

- same word may seem different or words may seem to move

- headaches when reading, watching TV or computer monitor

- patching one eye when reading

- difficulty tracking along line of print causing hesitant and slow reading

If visual problems, such as those above, are suspected, treatment should be sought from a qualified professional orthoptist. There are clinics at most main hospitals and referral can be made through the student’s GP, educational psychologist or the community paediatrician. Treatment may involve eye exercises and/or the use of colour – either tinted spectacles or the use of a coloured overlay.

Further information on visual issues is available on 2 Dyslexia Scotland leaflets

- ‘Dyslexia and visual issues’

- ‘Visual Issues - Frequently Asked Questions’

Which can be found at https://www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk/ our-leaflets [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

English as an Additional Language

For children who speak languages other than English at home, the assessment process will require very careful consideration, to accommodate the child’s first language as well as English, and this may require assistance from a professional who shares the same language as the child.

It must be remembered that the phonology of the child’s first language is likely to be different from English, and scripts too may be different. As an example, Polish children who have wholly developed literacy skills will have experience of decoding in alphabetic script but in the case of children exposed to logographic scripts, the relationship between sounds and symbols will be markedly different. Even although children may not have learned to read in their first language they will have been exposed to environmental print. The issue for teachers is to consider whether the children’s difficulties with language extend beyond them having English as another language.

’See ‘other factors to consider’ to access further information and resources to support English as an additional Language and dyslexia

Activity 11- Other factors to consider

In your Reflective Log complete the table inserting relevant questions to consider when evaluating and exploring the possible impact of other factors which can impact on the learner and the process of identifying dyslexia.

Once complete consider how you could engage the learner and their family with these questions.

Click ‘reveal’ to see some suggested questions

Discussion

| Factor | Questions | Further questions |

| Audio | Has the child had their hearing assessed? | Is there a history of hearing problems for the child or within their family? |

| Motivational | Does the learner appear to be disengaged | Is the curriculum accessible and appropriately differentiated? |

| Interrupted Learning | Have there been periods of interrupted learning?

| Were there high incidences of absences in the early years of primary school? Is there likely to be further interrupted learning e.g. travelling children, children of parents who are in the Armed Services? |

| Speech and Language | Has there been a history of speech and language delay/Development? Intervention? | What was the impact of any intervention? Is input ongoing? |

| Emotional and Behavioural | Has there been a change at home or out with school? | Have you identified any patterns or triggers to the pupil’s behaviours? |

| Social and Cultural | What is the family’s experience of education? | Do the family engage with education services? |

Motivational factors

| Do they have an interest in the topics? | Has there been engagement with the learner to explore areas they find interesting and incorporate this into the activities? |

| Gaelic Medium | Is Gaelic spoken at home or only in the school setting? | Did they hit their developmental milestones around literacy acquisition? |

| Motor skills/coordination and organisation | Does the child hold a pencil correctly? | Does the child have difficulty forming letters? |

| Does the child appear clumsy/have poor coordination? | Did the child learn to ride a bike within the typical age range? | |

| Visual | Has the child had their eyesight checked recently? | Is the child showing symptoms of or been assessed for visual stress? |

| English as an Additional Language | What languages are spoken at home? (It is more beneficial for a child to develop English if they are fluent in a first language spoken at home) | Is the child’s literacy progressing in their first language? |

Please note the list is not exhaustive and you will be able to develop your own questions which are relevant for the individual children and young people you are working with.

Access ‘The identification Pathway for Dyslexia’ which has been expanded to include additional supports and suggestions

What to look for